Jane Addams

[1860-1935]

Jane Addams won worldwide recognition in the first third of the twentieth century as a pioneer social worker in America, as a feminist, and as an internationalist.

Is the life of this female sociologist really as smooth as people think? Learn more about her life and growth in this article.

I. Jane Addams Biography

Jane Addams is best known for her groundbreaking activism in the social settlement movement, a radical offshoot of the progressive movement whose followers were so committed to progressivism that they made the decision to live next to oppressed people in order to learn from and support the socially outcast.

1. Who is Jane Addams?

Jane Addams (1860–1955) was an American activist, community organizer, supporter of world peace, and social philosopher in the early 20th centuries. However, the dynamics of canon formation meant that until the 1990s, her philosophical work was largely disregarded.

Although Addams' activism and accomplishments were widely praised by her contemporaries, commentators typically mapped her work onto traditional gender understandings. Male philosophers like John Dewey, William James, and George Herbert Mead were seen as having contributed original progressive thought, while Addams was seen as brilliantly implementing their theories. Jane Addams was much more than a capable practitioner, according to recent research by feminist philosophers and historians. Her dozen books and more than 500 articles have been published, and they demonstrate a strong intellectual dialogue between experience and reflection in the American pragmatist tradition.

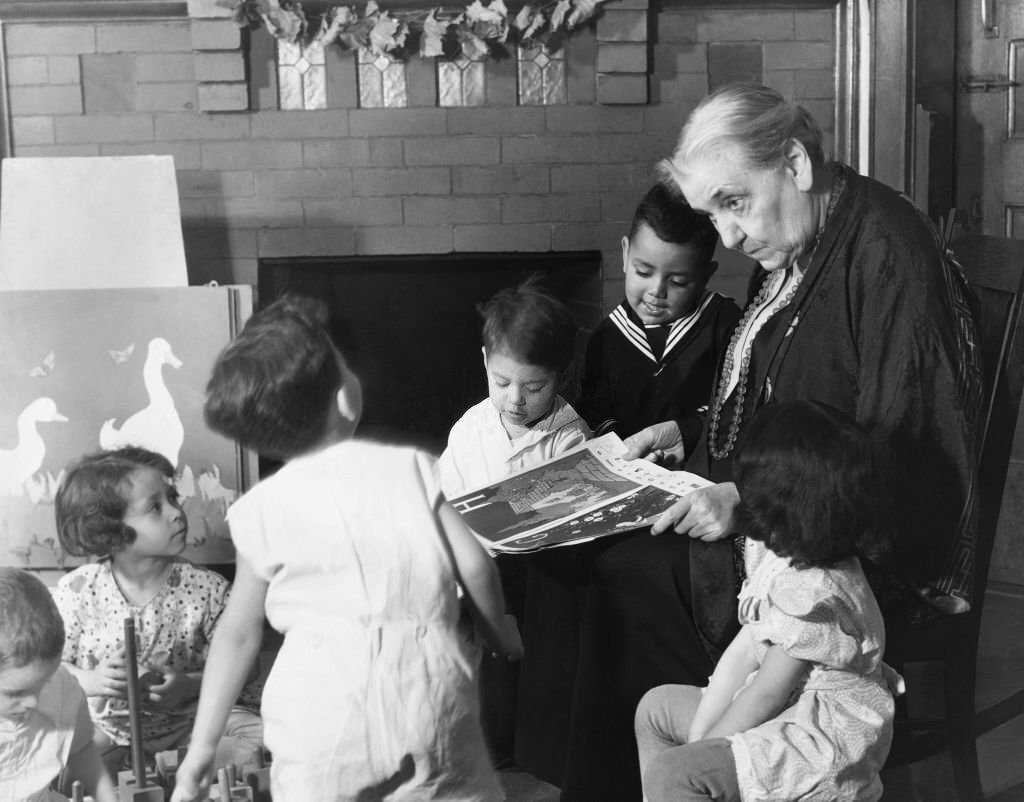

During the nearly 50 years she spent leading Hull House, a social settlement in Chicago, she was able to put her commitment to feminism, diversity, and peace into reflective practice. These encounters served as the inspiration for an intriguing philosophical viewpoint. Although Jane Addams saw her work on the settlement as a significant epistemological undertaking, she never lost sight of the humanity of her neighbors. Addams was a philosopher in the public eye who didn't mind getting her hands dirty.

2. Jane Addams early life

Compared to the many biographical accounts of Addams’ life, relatively few comprehensively consider her philosophy. The following is a brief account of some of her life experiences, which are closely related to her philosophical insights.

On September 6, 1860, Laura Jane Addams was born in Cedarville, Illinois. She grew up as the Civil War raged nearby and at a time when Darwin's Origin of the Species was becoming widely accepted. Being the daughter of prominent politician and prosperous mill owner John Addams gave her a material advantage during her early years. Mary, Jane's mother, passed away while giving birth to her ninth child when Jane was two years old. The young Jane Addams then adored her father and benefited both intellectually and emotionally from his care. Although John Addams was not a supporter of feminism, he wanted his daughter to pursue a higher education. He therefore sent her to Rockford Seminary, later known as Rockford College, an all-female college in Rockford, Illinois. Jane Addams joined a generation of women who were among the first in their families to enroll in college as a result. She gained confidence from living in a place that valued women at Rockford, where she also grew as a leader in both academia and society. Her peers and teachers recognized her for her leadership. After serving as the class valedictorian, Addams eventually led the charge to introduce baccalaureate degrees to the school and was awarded the first one.

Addams' options after college were limited, like those of many other women in her era. She made an unsuccessful attempt to get into medical school, and after her father passed away, she fell into a depressive state that lasted for almost ten years. Given that she had rejected both marriage and religious life, initially, the enthusiasm and spirit of her undergraduate college experience did not translate into any distinct career path. Additionally, Addams' illness resembled that of a later acquaintance of hers, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who was described as having an unnamed illness in The Yellow Wallpaper. As a member of the privileged class, Jane Addams traveled to Europe twice during this time in order to conduct her soul-searching. A pioneering Christian settlement house in London called Toynbee Hall was the destination of her second trip, and it would serve as the catalyst for her inspiration and eventual rise to fame on a global scale.

3. Jane Addams on Sociology

Hull House, the first settlement house in the US, was established in 1889 in the impoverished, industrial west side of Chicago by Addams and Starr. The idea was for educated women to teach the neighborhood's less fortunate residents all kinds of knowledge, from fundamentals to the arts and literature. In addition, they had a vision of women residing in the community center alongside the clients they assisted. Women who would go on to become prominent progressive reformers, including Julia Lathrop, Sophonisba Breckinridge, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, and Edith Abbott, joined Jane Addams and Starr in this endeavor. Under Addams' guidance, the Hull House team established a kindergarten and daycare for working mothers, offered job training, English language, cooking, and acculturation classes for immigrants, established a job-placement bureau, community center, gymnasium, and art gallery, and provided a variety of essential services to thousands of people each week.

In addition to publishing essays and delivering speeches about Hull House across the country, Jane Addams increased her efforts to advance society. She played a crucial role in successfully promoting the creation of a juvenile court system, better factory and urban sanitation laws, protective labor legislation for women, and more playgrounds and kindergartens throughout Chicago, along with other progressive women reformers. Jane Addams was a founding member of the National Child Labor Committee in 1907, which had a major impact on the 1916 adoption of the Federal Child Labor Law. At the University of Chicago, Addams spearheaded an initiative to found a School of Social Work, providing institutional backing for a brand-new career for women. In addition, Jane Addams was the first woman to hold the office of president of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections from 1909 to 1915. She also got involved in the women's suffrage movement by serving as an officer in the National American Women's Suffrage Association and writing pro-suffrage columns. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was also founded by her.

Jane Addams discovered her second major calling—promoting world peace—during World War I. She was an outspoken pacifist who opposed the United States' involvement in World War I, which hurt her popularity and led to harsh criticism from some newspapers. However, Jane Addams thought that people were capable of resolving conflicts amicably. She toured the warring nations with a group of female peace activists in an effort to bring about peace. She served as the Women's Peace Party's leader in 1915, and shortly after that she was elected president of the International Congress of Women. Jane Addams contributed to the founding of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in 1919, serving as its president from 1919 to 1929 and as honorary president until her passing in 1935. She also published essays and delivered speeches in support of peace around the world. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 for her efforts, becoming the first American woman to do so. She also wrote books advocating peace and one about her work at Hull House. Her health suffered after a heart attack in 1926, and despite her best efforts, she never fully recovered. On May 21, 1935, Jane Addams passed away.

II. Jane Addams Influences

Jane Addams was well-read and had a wide range of influences. But nobody was Addams' protégé. Addams selected intellectual sources that agreed with her idea of the role of sympathetic knowledge in advancing society. Here, a few key influences are mentioned.

While a student at Rockford Seminary, Jane Addams read works by Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881). Addams was especially drawn to Carlyle's social morality. He held that a divine will, acting through the heroes and leaders of society, was ultimately responsible for the universe's goodness and morality. When writing biographies of social reformers like poets, kings, prophets, and intellectuals, Carlyle also incorporated commentary that outlined his moral philosophy. Despite abandoning Carlyle's idea of individualistic heroism and his contempt for democracy, Jane Addams kept the idea of moral action being valued throughout her career. Additionally, morality according to Carlyle was based on right relationships with others and with God. The idea of sympathetic knowledge proposed by Addams has its roots in Carlyle's relational ethic.

John Ruskin (1819–1900), who believed that art and culture reflected the moral well-being of society, also had an impact on Jane Addams. Ruskin maintained a certain elitism in his belief that great people created great art, but he also saw such works of art as a reflection of society's health as a whole. A sense of aesthetics was connected to the plight of the oppressed. The appearance and activities of Hull House reflect Addams' elevation of art and culture, which is in line with Ruskin's aesthetics. According to Jane Addams, "Hull House has always seemed to go best with social life and the arts". Cultural pursuits, in Addams' opinion, strengthen fundamental human ties.

For Addams, Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) represented a different kind of hero. Tolstoy, unlike Carlyle, did not elevate individuals who stood out from the crowd as moral role models who held socially prescribed positions of authority. He valued solidarity with the average worker instead. Such polar opposite influences were made possible by Addams' enormous intellectual curiosity. From the time she finished college until her final years, Jane Addams read Tolstoy's works, and she frequently praised his writing in articles and book reviews. Tolstoy's emphasis on collaborating with the oppressed while penning books and essays that had a wider impact struck a chord with Addams' writings and work.

The shared experience of common labor should theoretically eliminate class boundaries. Hull House had provided Jane Addams with such a sense of community, and she had always valued Tolstoy's social critique. She did, however, recognize the value of wise leadership. The clubs needed to be set up, fundraising support needed to be secured, and meetings needed to be chaired. Tolstoy's labor demand was, in Addams' opinion, somewhat self-indulgent. She might be able to get rid of her upper-class guilt if she only worked at low-paying jobs. However, she would no longer be attempting to alter society's structure in a comprehensive manner. The civic activism philosophies of Jane Addams valued participation through constant presence and listening. Hull House had an effective organizational structure that was very flat and flexible.

If Addams' philosophy is thought of at all, it is typically compared to John Dewey's writings (1859–1952). Given their friendship and shared interests, this association is appropriate; however, her intellectual deference to Dewey is frequently exaggerated. One of the greatest American philosophers is Dewey. He is listed among the traditional group of founders of what is known as American Pragmatism, along with William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, and Josiah Royce. Because they held many of the same beliefs—such as the value of a strong democracy and the significance of education that engaged students' experiences—Addams was drawn to his work. The moment Jane Addams and Dewey met, they knew they were intellectual soul mates.

Additionally, Jane Addams kept in touch with William James (1842–1910), whose writings she frequently cites. James was a realist with a goal of enhancing cities, and Addams would have agreed with him. James and Addams shared a value for experience, and among "professional" pragmatists, his writing is most similar to Addams' in terms of readability and the use of concrete examples.

Jane Addams was influenced by a large group of feminist thinkers who came to work at the social settlement, in addition to the Romantics, the social visionaries , and the pragmatists. The complexity and diversity of Hull House's functions are reflected in the variety of ways in which it has been described. Being described as a pragmatist feminist "think tank" may be an underappreciated term. The intellectual, social, and political impact of the Hull House residents dwarfs that of the Cambridge intellectuals, despite the fact that the "Metaphysical Club" has achieved a mythical status among some in American philosophical circles. Residents of Hull House shared meals, beds, household duties, and social activism activities. While engrossed in their work and inspired by the numerous speakers and visitors to Hull House, they also discussed and debated politics, feminism, ethics, and culture. A distinctive intellectual collective that supported both theory and action was created as a result of the extended contact and shared gender oppression and mission.

Jane Addams was not a derivative thinker, despite having a wide range of influences, as many commentators have suggested. She drew on a number of notable theorists to develop her theories on social morality, but she never rigidly adhered to any one of them. She continued to have an impact on numerous people while making her original contributions to American and feminist philosophy.

III. Jane Addams Standpoint Epistemology

Given her dedication to sympathetic knowledge, Jane Addams can be seen as a forerunner of standpoint epistemology despite writing years before feminist philosophers gave the term its name. Compared to traditional philosophers, feminist philosophers have paid more attention to how context affects theory. Although there are lively discussions about the nature of objectivity in feminist philosophical circles, many have developed the idea that knowledge is in fact situated, including Dorothy Smith, Nancy Hartsock, Hilary Rose, Alison Jaggar, and Sandra Harding. Feminist standpoint theorists in particular value perspectives and theories that are derived from oppressed social positions, such as the experiences of women. Harding contrasts a feminist viewpoint with a passive one, describing it as something to achieve.Since all women have lived their lives in female bodies, they all have a female perspective. To gain a comprehensive understanding of power struggles, however, a feminist perspective necessitates an effort at taking a step back. Stakeholder epistemology can produce libratory knowledge that can be used to undermine oppressive systems by recognizing the perspectival nature of knowledge claims. How to give voice to multiple positions without resorting to hierarchies that prioritize some viewpoints over others is one of the difficulties of standpoint theory.

Through her work and writing at Hull-House, Jane Addams demonstrates her appreciation for the spirit of standpoint theory. Despite being born into a socially privileged position, her occupation immersed her in underprivileged communities. We finally know that we can only discover truth by a rational and democratic interest in life, and to give truth complete social expression is the endeavor upon which we are entering. Jane Addams poetically describes her moral obligation to meet, know, and understand others. Thus, the source and expression of social ethics are found in the identification with the common lot, which is the central tenet of democracy. Because we are aware that a delicate or weaker drink would not see us through the journey's end, moving forward as we must in the heat and commotion of the crowd, it is as though we have been thirsting at the great wells of human experience. Although these are admirable sentiments, one could argue that they were still expressed by an outsider. What does it mean to be an outsider?

The majority of Addams' life was spent in Chicago's Hull House neighborhood, which was home to many different immigrants. She didn't bring her data back to a university office or home in the suburbs. She was surrounded by crime, public corruption, prostitution, sweatshops, and other social ills while she lived and worked there. Jane Addams and Starr were outsiders when they founded Hull House, which was an oddity that neighbors regarded with suspicion. However, time, proximity, and a genuine desire to learn and assist won the neighborhood's respect. Insiders emerged from the outsiders. Jane Addams used first-hand knowledge gleaned from her social interactions when writing or speaking about single women laborers, child laborers, prostitutes, or first and second-generation immigrants. Addams used her time at Hull House as a springboard to promote socially disenfranchised viewpoints. She simultaneously worked to give the oppressed their own voice through English language classes, social clubs that promoted political and social debate, and college extension courses. In order to avoid making hasty generalizations, Jane Addams was reluctant to speak on behalf of others. "I never addressed a Chicago audience on the subject of the Settlement and its vicinity without inviting a neighbor to go with me," she said. Although Jane Addams was aware that the perspectives of the Hull House neighbors were important, she did not attempt to reach any universal moral truths.

Jane Addams thought that fostering sympathetic understanding of opposing viewpoints was crucial to advancing society. As a result, giving marginalized people a voice increases the likelihood that people will understand one another better and take actions that will improve their situation. Jane Addams tried to strike a delicate balance between respecting opposing viewpoints and looking for commonalities and continuities to build upon. The books by Jane Addams on young people, Youth and the City Streets, and elderly women, The Long Road of Woman's Memory, serve as examples of this. The latter work is a memoir of first-generation immigrant women that explores memory. Jane Addams, who knew most of the well-known women of her era, based her theory on the women who lived next to her at Hull House rather than the experiences of well-known women theorists or writers. In addition to drawing on her own experiences, Jane Addams also referenced those of people who were marginalized by society in her philosophical writings. Jane Addams values practice over theory. She didn't start off by putting forth a theory regarding these women. Instead, she recounted many of the tales she had heard from them before drawing conclusions about how memory worked. For Jane Addams, theory comes after practice. When it came to feminism or philosophy, Jane Addams was outlier among her contemporaries because she didn't just think working-class immigrant women should be given a voice; she also thought they had something significant to offer the world of ideas.

IV. Jane Addams Radical Meliorism

1. What is Meliorism

Meliorism is a defining characteristic of pragmatist philosophy, which is evident in Addams' writings because they have a more radical tone than those of other American pragmatists. Of all the American philosophers of her time, Jane Addams was the least elitist and most radical if "radical" is defined as opposing established power structures. Jane Addams consistently advocated for inclusive viewpoints that aimed to advance society. Jane Addams radicalized the scope of social progress, which pragmatists typically supported. Jane Addams advocates for "lateral progress," which she refers to as the improvement of everyone, as opposed to measuring progress by the best and brightest accomplishments.

According to Jane Addams, lateral progress meant that social advancement could not be claimed through the discoveries or pinnacle achievements of a select few but could only be truly discovered in social gains shared by all. Addams uses a metaphor to clarify the idea:

“ The man who demands consent and moves with the people is required to consult both the practicable and the absolute rights. He frequently feels compelled to achieve only Mr. Lincoln's "best possible" and frequently feels as though he must compromise with his strongest convictions. He must guide the people under his control toward a destination that neither he nor they can clearly see until they arrive at it.

In order to "provide the channels in which the growing moral force of their lives shall flow," he first needs to ascertain what people truly desire. What he does achieve, however, is supported and upheld by the sentiments and aspirations of many others and is not the result of his individual striving as a lone mountain climber out of sight of the valley. Although progress has been more lateral than perpendicular, it has been slower perpendicularly. While he did not instruct his contemporaries in mountaineering, he did convince the villagers to ascend a few feet higher. “

2. Jane Addams Radical Meliorism

Addams used the concept of lateral progress to address a variety of problems. She makes the case in her discussion of the function of labor unions that by working to improve conditions for all workers, unions are filling a crucial void left by society. The historically pro-labor Jane Addams makes it clear that she does not see collective bargaining as a goal in and of itself. As opposed to this, Addams sees unions as pioneers who win favorable working conditions for all of society: "trade unions are trying to do for themselves what the government should secure for all of its citizens; has, in fact, secured in many cases" . Jane Addams isn't concerned with enhancing the lot of any particular group of workers. Any feeling of hostility and suspicion is fatal to a democratic form of government because, despite the fact that each side may appear to benefit the most from looking out only for its own interests, the ultimate goal must be the welfare of the community as a whole . For Jane Addams, unions are crucial because they advance lateral progress for all Americans by enhancing working conditions, raising wages, reducing hours, and ending child labor.

Charity, while good, does not represent lateral development. While admirable, a short-term wealth transfer does not represent real progress in reducing economic inequality. Jane Addams never saw herself as a volunteer for a charitable organization, and she never referred to Hull House's work as charitable: "I am always sorry to have Hull House regarded as philanthropy" . Jane Addams aimed for lateral advancement that could be engendered by the group's will and made manifest through social institutions. According to her, if "society had been reconstructed to the point of offering equal opportunity for all," there wouldn't be a need for settlements. Jane Addams does not support an abstract, rights-based version of equal opportunity based on laissez-faire capitalism. Modern views of democracy as merely ensuring the right to participate are influenced by free market economics. Because everyone has a stake in lateral progress, or what we might today refer to as democratic socialism, Addams' approach to equal opportunity is set in a context of thriving democracy where citizens and social organizations look out for one another.

women's issues and gave voice to women's experiences, believing that a strong social democracy could only be achieved with the full participation of both men and women. Jane Addams exhibited feminist pragmatism when it came to issues like women's suffrage. "Some cherished project might be so altered by ignorant legislatures during the process of legal enactment that the law, as it was ultimately passed, injured the very people it was meant to protect, if women didn't have the right to vote with which to choose the men upon whom her social reform had become dependent. Women had learned that lawmakers who only want to appease the underrepresented are always likely to give them what they do not want. Note that Jane Addams makes a practical claim about the function of voting in proper democratic representation rather than arguing for the application of abstract human rights. It's not that Jane Addams is against rights; rather, she consistently chooses pragmatist justifications for feminism. Her male pragmatist colleagues sympathized with feminist claims, but they did not do so with the same vigor or consistency as Addams (1996).

Again, Addams' idea of lateral progress serves as an example of how she has been wrongly portrayed as merely a reformer. Marxist-style radical discourse has been linked to demands for radical reforms of social structures and systems. Although some might argue that such changes are desirable, they involve upheaval that will disrupt social relationships and come with a high risk of personal expense. Jane Addams sought significant social advancement through collaboration and exploitation of group intelligence. Her radical perspective steadfastly refused to give up on society's caring relationships and its people. Addams was a compassionate radical who combined theoretical ideas of social change with actual community organizing experiences. Although Addams was interested in solving social issues, her social philosophy could still be characterized as having a broadly construed radical edge.

V. Jane Addams on Socializing Care

At least three conclusions about Addams' relationship to feminist care ethics in the early 20th century are suggested by an analysis of her moral philosophy. One is that Addams' strategy for dealing with the pressing social issues of her time reflected the relationality and contextualization that are crucial to what is now referred to as care ethics. Two: Despite the fact that Addams practiced caring in response to others' needs, she adds an active, even assertive, dimension to care ethics that is uncommon in feminist theory. Third, Addams supports what might be referred to as "socializing care"—systematically implementing the routines and procedures of care in institutions of social welfare.

1. The development of care ethics

Although the word "care" is straightforward and frequently used, many feminist theorists have given it a specific ethical meaning. The recognition that traditional moral systems, especially those that are principle- and consequence-based, did not adequately address the complexity of the human condition was the original inspiration for the development of care ethics. These methods ignore relationships, emotions, timing, reciprocity, and creativity in favor of swift resolution of moral disputes. Therefore, applying rules or penalties can turn into a reductionist, formulaic response that yields opportunistic solutions to intricate, systemic problems. Although principles can be helpful for care ethicists, a concern for interpersonal connections tempers them. However, care theorists strive for a more robust and complex sense of morality that cannot ignore the context and people involved.

Principles and consequences can be significant in moral deliberation. For instance, there will likely be widespread agreement with the argument that those who spray paint graffiti on a building should be punished because they have harmed someone else's property. Care ethicists are curious but do not necessarily dispute this claim. Being a human, the person spray-painting may have motivations and circumstances that reveal additional factors that cannot be adequately addressed by the simple recognition of rule violations. This behavior might have been influenced by systemic problems with social opportunities, discrimination, or lack of voice. Care ethicists reorient the moral spotlight to concrete, situated individuals with feelings, friends, and dreams—people who can be cared for—instead of abstract individuals and their actions. To fully grasp the moral context, care ethics requires effort, experience, knowledge, imagination, and empathy. The end result is a richer understanding of the human condition, in which we are all actors and acted upon, rather than an absolving of personal responsibility.

2. The habits and practices of care in social institutions

Addams consistently eschews formulaic moral justifications of moral precepts or consequences in favor of relating her experiences in the Hull House neighborhood to a form of care ethics. Again, proximity is essential because she has firsthand experience with people, giving her the tools to respond in a compassionate manner. However, as a philosopher, Addams extrapolates her own circumstances to make predictions about those in comparable situations.

In The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, for instance, Addams discusses juvenile crime. She describes accusations made against young men who were brought before the Chicago juvenile court. The act of picking up coal from railroad tracks, hurling stones at railroad workers, or tearing down a fence fell under the category of disorderly conduct. Additionally, there was vagrancy, which included slacking off, spending the night on the streets, and wandering . Although Addams does not downplay the gravity of some of these offenses, she refrains from passing judgment and instead decides to look into the situation more thoroughly. She converses with the young men and inquires into their motives. "Their very demand for excitement is a protest against the dullness of life, to which we ourselves instinctively respond," she writes, identifying a listlessness and a desire for adventure that is unquenched by what the city has to offer .

3. Extend Care ethics

Last but not least, Jane Addams applies care ethics to society at large. She is not satisfied to separate social and personal morality. She wants democracy and all of its institutions to be cared for. For instance, Jane Addams believes that because social settlement residents live nearby these institutions, they have "an opportunity of seeing institutions from the recipient's standpoint." This viewpoint is important in her opinion, and she thinks it should eventually "find expression in institutional management" . Additionally, she uses language that acknowledges a caring component to distinguish the settlement's epistemological project from that of the university: "The settlement stands for application as opposed to research; for emotion as opposed to abstraction; for universal interest as opposed to specialization".

Social settlements serve as Addams' model of a democratic endeavor, but she also instills other institutions with the same compassionate principles. The establishment of juvenile courts in Chicago served as a prime illustration of compassion because it required contextualized consideration for the circumstances of young people. Adult education programs that dealt with real, current issues were developed to show consideration for Hull-House neighbors' needs. The Hull-House residents' behavior most prominently displayed care ethics in their openness to listening, taking in information, and responding. Jane Addams saw socializing care as taking part in a rich democratic ideal.

VI. Jane Addams Quotes

1. The good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into our common life.

2. True peace is not merely the absence of war, it is the presence of justice.

3. Nothing could be worse than the fear that one had given up too soon, and left one unexpended effort that might have saved the world.

4. I am not one of those who believe - broadly speaking - that women are better than men. We have not wrecked railroads, nor corrupted legislatures, nor done many unholy things that men have done; but then we must remember that we have not had the chance.

5. The essence of immorality is the tendency to make an exception of myself.

WHAT IS YOUR IQ?

This IQ Test will help you test your IQ accurately

Maybe you are interested