Michel Foucault

[1926–1984]

Michel Foucault was a major figure in two successive waves of 20th century French thought–the structuralist wave of the 1960s and then the poststructuralist wave. By the time of his untimely death, some considered Michel Foucault to be France's most famous living intellectual.

So what did Michel Foucault do during his life as a sociologist? Get to know more about Foucault and his career path in the article below.

I. Michel Foucault biography

Philosopher Michel Foucault (left) With Writer Claude Mauriac (right)

1. Who is Michel Foucault?

French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault (1926–1984) was a member of the structuralist and post-structuralist movements. He has had a significant impact on many humanistic and social scientific disciplines in addition to philosophy.

One might wonder if Michel Foucault actually qualifies as a philosopher. His books tended to be histories of the social and medical sciences, and his passions were literature and politics. He received his academic training in psychology, including its history, as well as philosophy. Nevertheless, almost all of Foucault's writings can be read as philosophically fruitful in one of two ways, or both: as a new (historical) way of carrying out philosophy's traditional critical project, or as a critical engagement with the ideas of traditional philosophers. In these two areas, this article will present him as a philosopher.

2. Michel Foucault early life

On October 15, 1926, Paul-Michel Foucault was born in Poitiers, France. He was a brilliant student who was also tormented mentally. Paul-André Foucault, his father, was a renowned surgeon and the brother of a local physician with the same name. Foucault's mother, Anne, was also the daughter of a surgeon and had long desired to pursue a career in medicine. However, she had to wait until the birth of Foucault's younger brother because at the time, women could not pursue such a career. The fact that a large portion of Foucault's work would center on the critical examination of medical discourses is undoubtedly no coincidence.

Michel Foucault attended school in Poitiers while it was under German occupation. Foucault excelled in philosophy and persisted in defying his father, who wanted the young Paul-Michel to follow his forebears into the medical field, despite having from a young age stated his intention to pursue an academic career. Michel Foucault may have dropped the "Paul" from his name due to his conflict with his father. Although Michel Foucault remained close to his mother, the father-son relationship remained chilly until the latter's death in 1959.

FRANCE - 1904: Poitiers (Vienne). The City hall.

Michel Foucault was once again residing in Paris at the beginning of the 1970s, which was a politically turbulent time. As the creator of the "Prisons Information Group," Michel Foucault threw himself into political activism, primarily in relation to the prison system. It began as a means of assisting political prisoners but ultimately aimed to give all prisoners a voice. In this context, Michel Foucault grew close to Gilles Deleuze, with whom he later had disagreements. During their friendship, Michel Foucault enthusiastically penned the foreword to the English translation of Deleuze and Félix Guattari's Anti-Oedipus.

After France's political climate significantly cooled in the late 1970s, Michel Foucault largely turned away from activism and into journalism. As the Iranian Revolution took place in 1978 and 1979, he covered it firsthand in newspaper dispatches. He started to spend an increasing amount of time instructing in the United States, where he had recently encountered a supportive audience.

Perhaps Michel Foucault contracted HIV while living in the US. He was diagnosed with AIDS in 1984, and his health deteriorated quickly. From his sickbed, he edited two volumes on ancient sexuality that were published that year, leaving the editing of a fourth and final volume unfinished. He left his estate to Defert with the stipulation that there would be no posthumous publications, and since then, this testament has come under ever-more-liberal interpretation.

3. Michel Foucault early work in psychology

Early works by Michel Foucault don't have a distinctly "Foucauldian" viewpoint. In these writings, Michel Foucault exhibits the phenomenological, psychoanalytical, and Marxist influences typical of young French academics at the time. The main publication by Michel Foucault during this time was his first monograph, Mental Illness and Personality, which was released in 1954. This compact book, written for a series aimed at students, begins with a historical overview of the different theories of psychological explanation before synthesizing views from evolutionary psychology, psychoanalysis, phenomenology, and marxism.

According to these viewpoints, mental illness can ultimately be explained as an organism's adaptive, defensive reaction to the conditions of alienation that a person experiences under capitalism. The book was initially revised by Michel Foucault in 1962 for a new edition titled Mental Illness and Psychology.The most Marxist content and the conclusion were changed as a result to align them with the theoretical viewpoint that he had by that point developed in his later book The History of Madness. This point of view contends that madness is a natural state and that alienation transforms madness into mental illness rather than actually causing mental illness. This was a viewpoint that later made Foucault unhappy, and he ordered the book to be temporarily taken off the shelves in France.

In the same month in 1954 as Mental Illness and Personality, Michel Foucault also published his other significant work from this early period: a lengthy introduction (much longer than the text it introduced) to the French translation of Ludwig Binswanger's Dream and Existence, a work of Heideggerian existential psychoanalysis. Michel Foucault here elaborates a novel account of the relationship between imagination, dream, and reality, going far beyond merely introducing Binswanger's text. He combines Binswanger's and Freud's insights, but makes the case that neither one of them comprehends the fundamental function of dreaming for the imagination. Dreaming is crucial to existence itself because it takes imagination to understand reality.

II. Michel Foucault Major Works

Since the time of Socrates, philosophy has frequently involved the task of challenging the current body of knowledge. Later, philosophers like Locke, Hume, and particularly Kant created a distinctly contemporary conception of philosophy as the critique of knowledge. The greatest contribution of Kant to epistemology was his insistence that the same critique that exposed the boundaries of our knowledge could also expose the prerequisites for its use. It turns out that what initially appeared to be merely contingent aspects of human cognition—like the spatial and temporal nature of its perceptual objects—are necessary truths. However, Michel Foucault suggests that this Kantian maneuver should be reversed. He suggests asking what, in the apparently necessary, might be contingent rather than what, in the apparently contingent, is actually necessary. His inquiries center on contemporary human sciences (biological, psychological, social). These assert to provide universal scientific truths about human nature but are frequently just the outward manifestations of a society's political and ethical commitments. Such assertions are refuted by Foucault's critical philosophy, which shows that they are the result of historical forces rather than objective truths. His major works all engage in criticism of historical reasoning.

1. Michel Foucault Histories of Madness and Medicine

History of Madness in the Classical Age, published by Michel Foucault in 1961, was inspired by his professional experience working in a Parisian mental hospital, his own psychological issues, and his academic psychology studies (he earned a license de psychologie in 1949 and a diplome de psychopathologie in 1952). The majority of it was written between 1955 and 1959, during his postgraduate Wanderjahren, while he held a series of diplomatic and educational positions in Sweden, Germany, and Poland. History of Madness is a study of how the modern idea of "mental illness" came to be in Europe. It is based on Foucault's extensive archival research as well as his critique of what he believed to be the moral hypocrisy of contemporary psychiatry.

According to conventional histories, the medical treatment of madness in the nineteenth century—which was based on reforms made by Pinel in France and the Tuke brothers in England—liberated the insane from the ignorance and brutality of earlier eras. However, Michel Foucault believed that the new theory that the insane were simply sick (mentally ill) and in need of medical care was not really an improvement over previous theories (e.g., the Renaissance idea that the mad were in contact with the mysterious forces of cosmic tragedy or the seventeenth-eighteenth-century view of madness as a renouncing of reason). Furthermore, he contended that the purported scientific neutrality of contemporary insanity treatments is actually a ruse for suppressing objections to traditional bourgeois morality. In essence, Michel Foucault argued that what was presented as an objective, indisputable scientific discovery (that madness is a form of mental illness) was actually the result of social and ethical commitments that were highly dubious.

The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault's subsequent history from 1963, also offers an analysis of contemporary clinical medicine. However, the socio-ethical critique is muted (aside from a few vehement passages), presumably because medicine (as opposed to psychiatry) has a larger body of objective truth and therefore fewer grounds for criticism. The Birth of the Clinic, in the vein of Canguilhem's History of Concepts, is consequently much closer to a conventional history of science.

2. Michel Foucault on The Order of Things

Les mots et les choses (also known as The Order of Things in English), the book that made Michel Foucault famous, is in many ways an odd interpolation into the evolution of his ideas. The book's subtitle, "An Archaeology of the Human Sciences," alludes to an expansion of the earlier critical histories of clinical medicine and psychiatry into other contemporary fields like economics, biology, and philology. The various "empirical disciplines" of the Renaissance and Classical Age, which predate these modern human sciences, are in fact extensively described.

The History of Madness or even The Birth of the Clinic, however, contain little to no explicit social critique. Instead, Michel Foucault provides an analysis of what knowledge meant in Western thought from the Renaissance to the present and how this meaning changed. The idea of representation is at the core of his explanation. Here, we concentrate on his discussion of representation in philosophical thought, which represents Foucault's closest interaction with conventional philosophical issues.

a. Classical Representation

Michel Foucault contends that representation was merely assimilated to thought from Descartes up to Kant : to think was to employ ideas to represent the object of thought. To be clear about what it meant for an idea to represent an object, he argues, is necessary. First of all, there were no features (properties) of the idea that by themselves made up the representation of the object, so there was no relation of resemblance at all. In contrast, knowledge was viewed as a matter of similarity between things during the Renaissance.

For Michel Foucault, the idea, or mental representation, is the key to Classical knowing. Classical philosophers might have disagreed about the precise ontological status of ideas , but they all agreed that they were "non-physical" and "non-historical" as representations, meaning that they could not be imagined as playing any role in the causal networks of the natural or human worlds. This led to the further conclusion that language could not play a fundamental role in knowledge, specifically as a physical and/or historical reality. Language might not be anything more than a higher-order tool for thought: a concrete expression of concepts that is meaningful only in relation to them.

b. Kant’s Critique of Classical Representation

According to Michel Foucault, Kant represents the great "turn" in modern philosophy (though presumably he is merely an example of something much broader and deeper). Kant questions whether concepts actually represent their objects and, if so, how (in terms of what). To put it another way, knowledge is no longer assumed to be contained solely in ideas, and it is now possible to consider that knowledge may originate from sources other than representation. This did not imply that representation had no connection to knowledge at all. It's possible that all knowledge still relies primarily on ideas representing objects. However, according to Michel Foucault, the idea that was only now (thanks to Kant) feasible was that representation itself might have descended from sources other than representation.

c. Language and “Man”

Descartes' cogito is a striking example of how Michel Foucault makes his point by demonstrating why it is unquestionably true in the classical episteme but not in the contemporary episteme. There are two ways to contest the cogito's authority. One is to argue that Descartes' conclusion is that the subject (the thinking self, the I) is something more than just the act of representing objects; as a result, we cannot move from representation to a thinker. Nevertheless, since thinking is representation, this is absurd for the Classical Age. The self as representative might not be "really real," but rather just the "product of" (constituted by) a mind that is real in a more comprehensive sense, is a second criticism. This argument, however, is only persuasive if we can consider the "more real" mind as possessing the self as an object in a manner other than as a representation of it. The claim that the self as representative is "less real" has no support in the absence of this. However, this is precisely what cannot be thought of in terms of classical philosophy once more.

d. The Analytic of Finitude

The very essence of man is his finiteness: the fact that, according to the contemporary empirical sciences, he is constrained by the various historical forces acting on him (organic, economic, linguistic). As a historically constrained empirical being, man must also be the source of the representations through which we understand the empirical world, including ourselves as empirical beings. This finitude is a philosophical problem. According to Kant, I (my consciousness) must serve as both the transcendental source of representations and an empirical object of representation.

How is that even possible? According to Micehl Foucault, the modern episteme will ultimately fail because it is historically realized that it is impossible. The historical case for this conclusion is sketched in what Michel Foucault refers to as the "analytic of finitude," which looks at the major initiatives (which together make up the core of modern philosophy) to understand man as "empirico-transcendental."

3. Michel Foucault From Archaeology to Genealogy

The Order of Things is explicitly described by Michel Foucault as a "archaeological" approach to the study of intellectual history. He published The Archaeology of Knowledge three years later, in 1969, as a methodological treatise that explicitly formulated what he believed to be the archaeological method that he had employed not only in The Order of Things, but also (at least implicitly) in History of Madness and The Birth of the Clinic.

In Foucault's terminology, epistemes or discursive formations are systems of thought and knowledge that are governed by rules other than those of grammar and logic. These rules operate below the consciousness of individual subjects and define a system of conceptual possibilities that establishes the limits of thought in a particular domain and period. In order to better understand the radically different discursive formations that dominated talk and thought about madness from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, Michel Foucault argued that books like History of Madness should be read as intellectual excavations.

The word "genealogy," according to Michel Foucault, was meant to evoke Nietzsche's genealogy of morals because it suggests complicated, banal, and disgraceful origins that are not at all related to any overarching narrative of progressive history. The goal of a genealogical analysis is to demonstrate that a certain way of thinking—which was also revealed in its fundamental components by archaeology and thus continues to be a part of Foucault's historiography—was the outcome of contingent turns in history rather than logically inevitable trends.

4. Michel Foucault on History of the Prison

The 1975 book Discipline and Punish is a historical analysis of the evolution of the "gentler" modern method of incarcerating criminals as opposed to torturing or killing them. Michel Foucault specifically emphasizes how such reform also becomes a vehicle of more effective control, while also acknowledging the element of genuinely enlightened reform: "to punish less, perhaps; but certainly to punish better" (1975 [1977: 82]). He goes on to say that the modern prison is modeled after factories, hospitals, and schools, and that the new form of punishment serves as the blueprint for social control as a whole. However, we shouldn't assume that the use of this model was a direct result of decisions made by a centralized controlling body. The analysis of Michel Foucault demonstrates how institutions and techniques that were created for various and frequently quite innocent purposes,created the current system of disciplinary power as they came together.

Foucault's genealogies also have unique philosophical ramifications because they historicize the body. They cast doubt on the naturalistic explanatory model that sees science-discovered aspects of human nature as the foundation for such complex facets of behavior as sexuality, insanity, or criminality. The fact that contemporary penal institutions function with a very different kind of rationality than those that are only designed to exact revenge through suffering is a central thesis in Foucault's historical analysis of those institutions. He successfully highlights the dual purpose of the current system, which combines legal and scientific procedures to both punish and correct. For instance, Michel Foucault argued that the introduction of criminal psychiatry into the legal system at the start of the nineteenth century was a part of the gradual transition in penal practice from From the action to agency and personality, the focus shifts from the crime to the criminal. The "dangerous individual," a novel concept, referred to the danger that might be present in a criminal.

Without the development of new types of scientific knowledge, such as criminal psychiatry, which allowed for the characterization of criminals in themselves, beneath their acts, the new rationality could not function in the existing system in an effective manner. According to Michel Foucault, this change led to the emergence of new, sneaky types of violence and dominance. Discipline and Punish ability to illuminate the subject formation processes at work in contemporary penal institutions is what gives it its crucial significance. Modern prisons punish their inmates not only by denying them their freedom, but also by classifying them as dangerous criminals and delinquent subjects.

5. Michel Foucault on History of Modern Sexuality

The original plan for Foucault's history of sexuality was to simply apply the genealogical framework of Discipline and Punish to the subject of sexuality. According to Michel Foucault, the various "sciences of sexuality," including psychoanalysis, have a close relationship with the social hierarchies in contemporary society and are therefore excellent candidates for genealogical study. The History of Sexuality, Vol. I: The Will to Knowledge, the first book in this series, was published in 1976 and was meant to serve as the introduction to a number of studies on specific facets of contemporary sexuality (children, women, "perverts," population). It provided an overview of the overall history project while outlining the fundamental premise and recommended approaches.

In addition to moral worth, sexuality also affects one's health, desire, and sense of self, as demonstrated by Michel Foucault. Additionally, subjects must be truthful about themselves by confessing their sexual orientation. Modern sexuality, according to Michel Foucault, is characterized by the secularization of religious confessional practices. Instead of confessing one's sexual desires to a priest, one now sees a physician, therapist, psychologist, or psychiatrist.

Michel Foucault had to reconsider the nature of power in order to challenge the prevalent theory regarding the connection between sexuality and oppressive power. His main argument is that power is fundamentally productive rather than repressive. The true and authentic expressions of a natural sexuality are not suppressed or forbidden in order for it to function. Instead, it shapes the ways in which we experience and conceptualize our sexuality through scientific discourses and cultural normative practices. Our sexual identities are "the internal conditions" of power relations.

6. Michel Foucault on Sex in the Ancient World

Foucault's final involvement with conventional philosophy results from his turn toward antiquity in his final years. It had been intended for The History of Sexuality to be a multi-volume work on various topics in a study of contemporary sexuality. The first volume, which was previously covered, served as an introduction. Les aveux de la chair, a second book by Michel Foucault that examined how Christian confessional practices gave rise to the modern concept of the subject, was never made public. (It was released as a posthumous book in 2018). His concern was that to properly understand the development of Christianity, it was necessary to compare it to ancient notions of the ethical self, so in his final two books (1984) on Greek and Roman sexuality: The Use of Pleasure and The Care of the Self.

In addition to continuing his effort to rethink the topic, Foucault's most recent two books aim to contribute to the task of rethinking ethics. Now, the emphasis is on the ways in which subjects come to understand themselves and the methods by which they alter their mode of being. Michel Foucault persisted in his pursuit of the notion that the self was something that had been—and must be—created and that there was no true self that could be understood and liberated. He did this through his study of ancient Greek ethics. But in his later research on the topic, a completely new axis of analysis is evident. His more recent research emphasizes the subject's own role in this process, in contrast to his earlier genealogical studies, which focused on the ways that power/knowledge networks constituted the subject. As a result, it provides a more nuanced understanding of the topic. Power does not merely construct subjects; subjects also participate in that construction and alter themselves through self-modifying practices. They actively reject, adopt, and change forms of being a subject rather than being passive bodies. By creatively reshaping oneself and one's lifestyle, one can challenge normalizing power by looking for new opportunities for identities, experiences, pleasures, connections, ways of being, and ways of thinking.

III. Michel Foucault Legacy

There should not be a posthumous publication of any writings by Michel Foucault that he did not publish during his lifetime, according to his last will and testament. However, because Michel Foucault had permitted the recording of his lectures, his estate decided that this amounted to authorization for edited versions of his public lectures to be published using his notes and tape recordings. This choice allowed print editions of the annual courses of lectures he gave from 1970–1971 through 1983–1984 at the Collège de France (aside from a sabbatical year in 1976–1977) as well as other lectures he delivered in various universities around the world. Due to this, a vast amount of crucial information is now accessible. While some of it presents ideas that are unique, some of it covers work that was later published.

Foucault's theories on government and governmentality are introduced in the lecture series Security, Territory, Population (1977–1978) and The Birth of Biopolitics (1978–1979), which have had a particularly large impact. "Government" becomes Foucault's preferred term for authority, and "governmentality" serves as his primary theoretical framework for examining its logic, tactics, and practices in the contemporary era.

Government, according to Michel Foucault, historically referred to a variety of activities, such as controlling a territory and its citizens or guiding the soul through religion. However, in the context of the modern state, government has come to mean controlling a population. The focus of modern forms of government on population necessitated and promoted the growth of specialized knowledge, including statistical analysis, macroeconomics, and bioscience. Because the modern state had to protect the lives and well-being of its citizens, Michel Foucault refers to this type of politics as biopolitics.

One of the main objectives of Foucault's lectures was to explain and analyze how governmental rationalities have changed over time. His analysis demonstrates the two key components of contemporary governmental rationality. On the one hand, the emergence of a centralized state with a highly organized bureaucracy and administration is indicative of how the modern state has developed. Despite the fact that this feature is frequently discussed and criticized in political theory, Michel Foucault also notes the emergence of a second feature that seems to be at odds with this development. He asserts that individualizing power, or as he also refers to it, "pastoral power," characterizes the modern state. This is a form of power that depends on personalizing life knowledge. In an effort to permanently and continuously control people's behavior, the modern state required the creation of power technologies geared toward people. As a result, the state begins to interfere with people's daily activities, such as their eating habits, mental health, and sexual preferences.

Governmentality analysis does not take the place of Foucault's earlier understanding of power. His analytical approach is similar to the one he employed to investigate the strategies and routines of power in the context of specific, regional institutions, such as the prison. The historically particular rationalities built into practices needed to be examined but also challenged. At the same time, Foucault's examination of governmentality gives his understanding of power new and significant dimensions. While he could only study disciplinary power in the context of specific institutional settings, he was able to study larger, more strategic developments with the concept of government. He was able to apply his knowledge of power to areas that were previously thought of as the purview of political theory, such as the state. Michel Foucault was also able to make his understanding of resistance clearer by conceiving of power as a form of government.

The concept of critique as a form of resistance is now essential because government refers to strategic, regulated, and rationalized modes of power that must be justified through forms of knowledge. To govern does not mean to physically control how passive objects behave. Offering justifications for why those who are governed should follow orders implies that they have the right to object to these justifications. Governmentality has historically evolved in tandem with the practice of political critique, according to Michel Foucault. Critique as a practice must challenge the justifications for that form of government, including its legal principles, procedures, and tools.

Michel Foucault also emphasizes that neoliberal governmentality should be viewed as a particular way of producing subjects: it produces an economic subject structured by specific tendencies, preferences, and motivations. It aspires to produce social circumstances that not only necessitate and encourage competition and self-interest but also result in them. In order to demonstrate how neoliberal subjects are perceived as navigating the social realm by continually making rational decisions based on economic knowledge and the strict calculation of the necessary costs and desired benefits, Michel Foucault discusses the work of American neoliberal economists, in particular Gary Becker and his theory of human capital. They must develop the necessary economic knowledge to be able to calculate costs, risks, and potential returns on the capital invested. These subjects must make both long-term and short-term investments in various facets of their lives.

IV. Michel Foucault Quotes

“People know what they do; frequently they know why they do what they do; but what they don't know is what they do.”

― Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization

-----

“I don't feel that it is necessary to know exactly what I am. The main interest in life and work is to become someone else that you were not in the beginning.”

-----

“Where there is power, there is resistance.”

-----

“What strikes me is the fact that in our society, art has become something which is related only to objects and not to individuals, or to life. That art is something which is specialized or which is done by experts who are artists. But couldn't everyone's life become a work of art? Why should the lamp or the house be an art object, but not our life?”

-----

“I'm no prophet. My job is making windows where there were once walls.”

-----

“Knowledge is not for knowing: knowledge is for cutting.”

-----

“...if you are not like everybody else, then you are abnormal, if you are abnormal , then you are sick. These three categories, not being like everybody else, not being normal and being sick are in fact very different but have been reduced to the same thing”

-----

“I don't write a book so that it will be the final word; I write a book so that other books are possible, not necessarily written by me.”

-----

“The strategic adversary is fascism... the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behavior, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us.”

-----

“Maybe the target nowadays is not to discover what we are but to refuse what we are.”

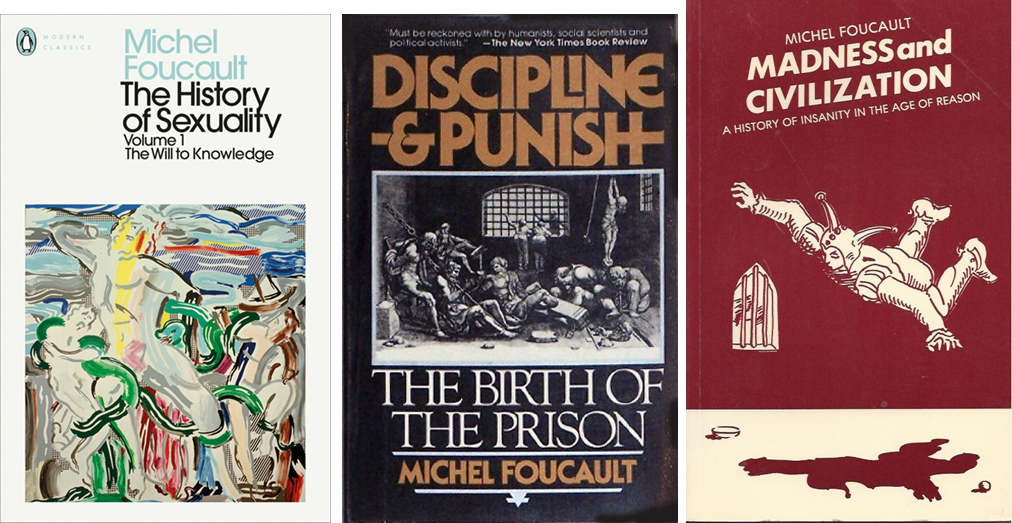

V. Michel Foucault Books

Michel Foucault was one of the most influential thinkers in the contemporary world. Michel Foucault was a social scientist and an intellectual historian who taught the history of philosophical systems at the Collège de France. His most well-known books include The History of Sexuality, Discipline and Punishment, and Madness and Civilization.

1. The History of Sexuality

Michel Foucault provides an iconoclastic examination of why we feel compelled to continuously analyze and discuss sex as well as the social and psychological power structures that lead us to focus on our sexuality when addressing questions about who we are.

2. Discipline and Punishment

The most important philosopher since Sartre, a masterful work. A brilliant thinker contends in this essential work that lauded reforms like the outlawry of torture and the development of the modern prison have only shifted the focus of punishment from the prisoner's body to his soul.

3. Madness and Civilization

Michel Foucault examines the archeology of madness in the West from 1500 to 1800. from the late Middle Ages, when insanity was still considered part of everyday life and fools and lunatics walked the streets freely, to the time when such people began to be considered a threat, asylums were first built, and walls were erected between the "insane" and the rest of humanity.

WHAT IS YOUR IQ?

This IQ Test will help you test your IQ accurately

Maybe you are interested