Alexis de Tocqueville

[1805-1859]

Alexis de Tocqueville is a political scientist, historian, and politician best known for Democracy in America, a critical examination of the United States' political and social systems in the early nineteenth century.

What made Alexis de Tocqueville such a famous sociologist in his era ? Get to know about Alexis’ life and career path in the article below.

I. Alexis de Tocqueville biography

The influential book "Democracy in America" (1835), written by French sociologist and political theorist Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859), was based on his extensive observations made while researching the American prison system in 1831. Tocqueville's writing continues to be an important resource for explaining America to Europeans and for explaining Americans to themselves because of its sharp observations on equality and individualism.

1. Who is Alexis de Tocqueville?

In 1805, Alexis de Tocqueville was born into an aristocratic family that had recently experienced the upheavals of France's revolution. During the Reign of Terror, both of his parents had served time in prison.

Alexis de Tocqueville attended college in Metz before studying law in Paris and being appointed a magistrate in Versailles, where he also met his future wife and made friends with Gustave de Beaumont, another lawyer.

2. Alexis de Tocqueville early life

When Louis-Philippe, the "bourgeois monarch," ascended to the French throne in 1830, Tocqueville's aspirations for a successful career were momentarily put on hold. In order to study the American penal system after being unable to advance, he and Beaumont obtained permission and sailed for Rhode Island in April 1831.

Tocqueville and Beaumont traveled for nine months by steamboat, by stagecoach, on horseback, and in canoes, visiting America's prisons along the way, from Sing-Sing Prison to the Michigan woods, and from New Orleans to the White House. Alexis de Tocqueville spent a week in Pennsylvania speaking with every prisoner at the Eastern State Penitentiary. He visited President Andrew Jackson in Washington, D.C., during open hours, and the two men mingled.

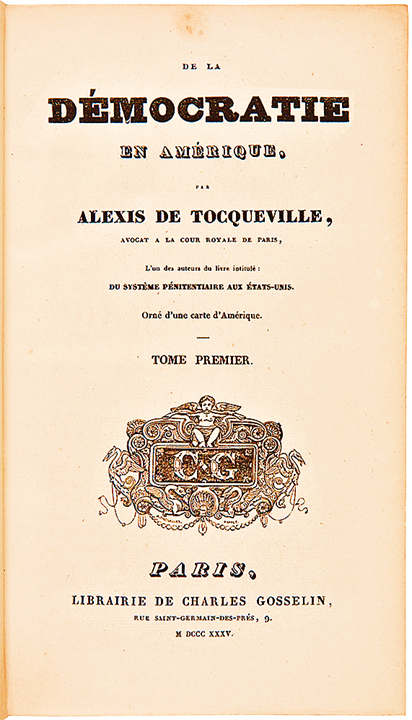

In 1832, the travelers went back to France. They swiftly released their report, which Beaumont contributed significantly to and was titled "On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application in France." Alexis de Tocqueville got to work on a more thorough examination of American politics and culture, which he eventually published as "Democracy in America" in 1835.

II. Alexis de Tocqueville in Sociology

1. Alexis de Tocqueville Contribution

Few realize that Alexis de Tocqueville's observations of America contributed to a sociological perspective on countries suffering under tyranny and its effects. He is best known for his opinions on democracy in America and for his work as a political scientist, which helped him establish a renowned reputation in France.

The most cutting-edge illustration of equality in practice came from the United States. Although he admired American individualism, he cautioned that when "every citizen, being assimilated to all the rest, is lost in the crowd," a society of individuals can quickly become atomized and unintentionally uniform. He believed that in order to resolve disputes with the state, a society of individuals lacked the intermediary social structures offered by conventional hierarchies. A democratic "tyranny of the majority" that compromises individual rights might be the outcome.

At least three aspects of Tocqueville's thinking make him relevant to sociology: his intense interest in social observation in France, Britain, Algeria, and America; his historical approach to understanding society—the significance of placing contemporary changes in a historical context; and his causal and comparative imagination, which stemmed from his desire to learn the reasons behind some of the patterns and differences he noticed in comparable societies. The writings of Alexis de Tocqueville influenced discussions of liberalism and equality in the 19th century, and they were rediscovered during the 20th century sociological debates on the causes and solutions to tyranny. Politicians, philosophers, historians, and anyone else trying to understand the American psyche continue to read and cite "Democracy in America" frequently. But in the end, drawing the conclusion that Alexis de Tocqueville contributed a significant set of ideas to modern sociology—the endeavor to develop a scientific understanding of the contemporary world—is not incorrect.

2. Alexis de Tocqueville – A voice in sociological conversations of today

The unavoidable notion of equality of conditions and its effects on societal cohesion and functioning in a democratic society were examined by Alexis de Tocqueville. In contrast to his contemporaries Comte and Marx, Tocqueville is primarily regarded neither as a precursor nor as a classic in sociological thinking, despite the fact that this raises legitimate sociological questions.

The book's greatest strength is that it rekindles Tocqueville's influence on social science debates about democracy, equality, and popular sovereignty. Alexis de Tocqueville regarded the United States as the best illustration of how a society built on equality and popular sovereignty can operate without recurrent revolution and despotism.

3. Alexis de Tocqueville main ideas

The 12 essays in this collection also discuss contemporary issues with society and religion, linguistic innovation, literary style, and the comparative method for examining issues with racial, ethnic, and gender inequality in societies. In addition to concepts of penal systems in democratic societies, they also examine the conflict between the principle of popular sovereignty and the de facto vertical exercise of power and command. A concluding chapter examines Tocqueville's analysis of the political, social, and intellectual forces that led to the French Revolution and attempts to explain why he was unable to finish the second volume of his Ancien régime et la révolution. This was a result of the obstacles he ran into while trying to prove his theory that the revolution's erratic course from 1789 to 1798 was caused by administrative centralization and social disintegration.

Gordon makes compelling arguments in his introduction chapter for Tocqueville's status as a pioneer of sociological thought, citing his comparative and historical approach, non-theological analysis of religion, and use of concepts that later came to be known as ideal types. Daniel Gordon explains the significance of this volume and the reasons why sociologists and political scientists should read it in addition to Alexis de Tocqueville experts in order to evaluate Tocqueville's applicability to current sociological discussions: The goal is to create hypothetical sociological conversations that include Tocqueville's voice. The current volume does that, and I don't think any other recent volume has done it before.

Alexis de Tocqueville follows suit. To the extent that Tocqueville's questions apply to concerns about democracy, individualism, liberty, centralization, and other topics in the twenty-first century, they are more or less addressed in this volume through the lens of historians, sociologists, and philosophers from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including Marx, Du Bois, Foucault, Furet, and Habermas. One advantage of this collection is that it also includes opposing viewpoints, such as that of Judith Adler, who claims that Tocqueville never considered himself a sociologist and never used the term sociology, and that he was more of a moralist in the Pascalian tradition. Alexis de Tocqueville was a modern author, regardless of this moralist vein, as Daniel Gordon demonstrates in an analysis of Tocqueville's avant-garde lexicon. Additionally, Tocqueville was well aware of the way that democracy alters language in order to foster a passion for broad ideas. As a result, he cautions his readers that his descriptions and conclusions about a democratic society could be wrong.

Alexis de Tocqueville believed that there are multiple realities in the social world; as a result, he practiced a detached perspectivism that was motivated by tolerance for ambivalence, in contrast to the 'binary' unmasking style. Therefore, according to Baehr, it is unlikely that Alexis de Tocqueville will experience "some belated surge of popularity," as his ideas don't lead to radical social movements. Other contributors discuss Tocqueville's errors in judgment, inconsistencies, and contradictions without resorting to an unmasking style, such as the fact that his criticism of slavery in the United States was not resolute enough and that, as a politician and member of the French parliament, he defended French colonialism in Algeria.

He didn't appear to be a proponent of women's liberation, nor did he seem to think that the fact that women in the United States were confined to the home and denied the right to vote was in conflict with the idea of equality. Furthermore, Tocqueville's optimism that political and civil associations could inspire and educate people to enjoy political liberty and equality for all time was unjustified. The conflict between the government's vertical exercise of power and the horizontal relations among equal citizens in the exercise of popular sovereignty was not resolved. Since then, the issue has, at best, been theoretically solved.

4. Alexis de Tocqueville impact on Sociology

This book serves as a reminder to modern social scientists and perhaps even more so to politicians that equality is most often created by "mores" rather than laws. Additionally, Alexis de Tocqueville has emerged as a role model for those who aim to examine social reality from as many perspectives as they can, rather than through "mind-numbing specialization" (Hess). Last but not least, we are reminded of Tocqueville's warning about the threats to individual liberty posed by democratic societies. Even if these democratic societies worked tirelessly to achieve equality, it would not accurately reflect how much freedom an individual actually had.

All of the traits mentioned here, including a love of detailed observation and description, an interest in learning about social causes, a comparison-based imagination, and a framework of thought that emphasizes the value of history, are actually beneficial intellectual elements for modern sociology. He was content to study the variety of social phenomena he had found and to formulate some potential, historically constrained causal theories about how these historically specific phenomena might operate. Sociologists can continue to use Alexis de Tocqueville's theories and observations to comprehend contemporary society because they remain as pertinent today as when they were first published.

III. Alexis de Tocqueville Major Works

1. Democracy in America

a. What is “ Democracy in America “

The two volumes of De la Démocratie en Amérique were released in 1835 and 1840, respectively. It follows a nine-month journey Alexis de Tocqueville took through America in 1831 and 1832 with Gustave de Beaumont. It is not a travelog or even an in-depth analysis of American political institutions. The book offers a wealth of unique and fascinating insights into American culture, including the country's government, laws, and, most importantly, the people's habits or mores, which Alexis de Tocqueville defined as the entirety of the country's political, intellectual, religious, and social life. Tocqueville, however, wanted to do more than just write about America. According to him, he came to America in search of "an image of democracy itself."

America presented a special opportunity to depict the great "democratic revolution" taking place in the West because it was the country where democracy was most developed and perfected. Thus, Tocqueville's "America" serves as the unique case study for the interpretation of contemporary democracy, and his "Americans" serve as the model civic society.

Alexis de Tocqueville analyzes America through the lens of democracy, or the equality of circumstances, throughout the two volumes of his work. He explains how America's geography and geopolitical situation, as well as the culture and laws of the country's original settlers, had been favorable to a government where equality was the fundamental and guiding principle. He also discusses how the Puritans, America's "point of origin," contributed to the nation's ability to combine equality with freedom and individual rights.

b. Alexis de Tocqueville main idea in “ Democracy in America “

Alexis de Tocqueville, who claimed to have coined the term "individualism," contends that democratic equality breeds the threat of individualism. Tocqueville draws a line between selfishness and individualism. Selfishness is the pursuit of an apparent personal good at the expense of the greater good and can be found everywhere and at any time. Modern democracy's individualism is a mistaken theoretical doctrine that maintains that each person is fundamentally alone in the world. Only insofar as everyone else is the same and in the same state of radical solitude can there be society. Democratic man feels strongly his weakness in the face of many other "individuals," despite his conviction that he must be self-sufficient. Man's increasing turn away from public life and toward private life is the practical manifestation of individualism.

Alexis de Tocqueville worries that democratic individualism will lead to what he dubbed "soft despotism" in his second book and "tyranny of the majority" in his first. According to the English liberal John Stuart Mill, this doesn't refer to a majority forcing its will on a minority; rather, it refers to democratic peoples' propensity to create bureaucratic structures and come up with highly abstract political ideas, which deprive them of the freedom to act or think for themselves except in the most insignificant of circumstances. Thus, democracy might endanger both political and intellectual freedom. This new despotism, according to Alexis de Tocqueville, may be more pernicious than the traditional kind because it threatens to enslave people's souls as well as their bodies.

In his analysis of America, Alexis de Tocqueville looks into potential solutions to the risks that democracy poses. He emphasizes the value of the "spirit of the New England township," which calls for residents to come together to discuss issues of shared interest. He writes admiringly about how Americans like to band together to pursue their political, social, and religious objectives. Such direct encounters with political and sub-political deliberation and action give the American a practical understanding and help him rise above his particular concerns. Above all, Alexis de Tocqueville emphasizes the role of American religion as a vital restraint on democratic individualism's excesses. Alexis de Tocqueville asserts that American religion teaches that "freedom" means the freedom to do only what is right, in the words of Puritan founder John Winthrop. This provides a fixed moral orientation and acts as a crucial check on the individualistic impulse of the democratic man. It opposes materialism and the idea that man is entirely independent and must determine what is permissible or not according to his own standards. Deliberation, associations, religion, and other facets of American life instill in Americans "self-interest rightly understood," the idea that achieving one's own interests necessitates acting in the interests of others.

c. A message from Alexis de Tocqueville

The "habits of the heart" that allow Americans to fend off democratic dangers do not completely eliminate them, according to Alexis de Tocqueville. One excellent example is American religion. Even though American religion can limit freedom and restrain materialism, it is also susceptible to corruption and can easily veer into a shallow pantheism that we might now refer to as "spirituality." Alexis de Tocqueville suggests that Americans are religious, but that they occasionally use religion as a cover for self-worship. Tocqueville thus differs from his contemporaries or close contemporaries, such as Mill, Madison, Constant, and Guizot, in that he is, generally speaking, less optimistic that problems with democracy could be solved by a proper arrangement of laws or institutions. Tocqueville believed that democracy was woven with a soft despotism and apathy. Alexis de Tocqueville nevertheless wants to inspire people to consider these weaknesses while also cultivating a passion for moral, political, and intellectual excellence.

2. The Old Regime and the Revolution

a. What is “ The Old Regime and the Revolution ”

L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution is not a traditional history of the French Revolution, just as Democracy in America is not a history of the United States. Because the "revolution" Alexis de Tocqueville was referring to was the leveling of social conditions that had occurred throughout Europe since the early Middle Ages and was not just a French phenomenon, the book was not titled L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution Française.

Tocqueville refers to the advancement of equality as a "providential fact" in the introduction to Democracy in America. He does this in the Old Regime by questioning the French Revolution's revolutionary nature. Tocqueville explains how kings, noblemen, bourgeois, and the general populace had all unwittingly contributed over many centuries to the production of equality, in contrast to contemporary claims that the French Revolution swept away deeply ingrained class distinctions.

b. Main Idea

Tocqueville discusses how and why France struggled to moderate or guide this equality revolution, and how "Bonapartism" or bureaucratic despotism is one of its logical outcomes. He then turns his attention to the case of France. The great "revolution" has produced bureaucratic tyranny, which is just as "democratic" as the democratic and prosperous United States. Tocqueville nevertheless harbors the dream that Frenchmen will lead the revolution for equality in their nation. He cites the Languedoc region as an example of how self-government practices could be maintained despite centralization because it had resisted Parisian centralization and had maintained some autonomy.

However, it is far from clear whether Tocqueville thinks decentralizing France and giving its regions back their political power is feasible or desirable. Tocqueville would prefer to arouse in his readers a "spirit" of intellectual and liberal independence. Languedoc is a more complex case than the New England township, which Tocqueville praises and considers to have been a significant source of American strength. This reflects Tocqueville's overarching pessimistic assessment of France's political history.

IV. Alexis de Tocqueville on Philosophy and Politic

1. Philosophy

The last days of the July Monarchy, the Revolutions of 1848, and the Second Republic's disastrous politics and constitution-writing are all covered in Tocqueville's political autobiography. Tocqueville had served as a deputy for many years, but only during these turbulent few years did he play a significant political role. The piece gives the reader an insightful look into a political philosopher's political thinking and behavior. Because Tocqueville offers an unusually candid evaluation of his own political strengths and weaknesses. He describes how his philosophical outlook and distaste for the "middling" and rough-and-tumble nature of politics made him less skilled in his political scheming.

The inclusion of a "one-term" presidential limit in the 1848 constitution, which made way for a Bonapartist takeover of France, was Tocqueville's greatest political blunder. Tocqueville's candid admission of his political shortcomings serves to highlight his sharp political and theoretical insight as well as his exceptional capacity to predict the nature of the revolutions of 1848. In this book, Tocqueville demonstrates how the motivation for equality and abstract "social" doctrines were the real drivers of those revolutions. This decision is consistent with his overarching theoretical position on the "march of equality" in Western nations, which was developed in his two major works.

2. Politic

Up until 1851, Tocqueville will serve in the Assembly. He defended his anti-slavery and pro-free trade views there, and after visiting Algeria in May 1841, he pondered colonization generally. The brutality of the French military under General Bugeaud's command disturbed him:

"What can a country's future be if such men are left in charge? The officers are not only violent, but they also openly profess the soldier's stupid and ferocious hatred of the civilian! Where else could this string of injustices and violence lead but to native uprising and European ruin? For the time being, civilization is on the side of the Arabs. "

He was chosen as the General Councilor of the Manche Department in the Sainte Mère Eglise canton in 1842. He was chosen as Chairman of the General Council on August 6, 1849, in the second round of voting by 24 votes out of 44 cast votes. He held this position until August 1852. He announced the revolution in a foresighted speech he delivered in January 1848. He was chosen to serve in the 1848 Constituent Assembly following the overthrow of the July Monarchy. He was a member of the Commission that wrote the French constitution of 1848. Above all, he stands up for decentralization, bicameralism, and the election of the president of the republic using a universal vote. In 1849, he won a seat in the Legislative Assembly, where he later rose to the position of vice president.

He preferred Cavaignac over Louis Napoleon Bonaparte as a candidate for the presidency of the republic, but he accepted the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs and joined Odilon Barrot's second administration on June 2. He has the temperament of a statesman. He assisted in resolving several issues within a short period of time, all of which could have gotten France involved in wars. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte changed his government on October 31, 1849. The accomplices should be seated after the ministers. The president could stage a coup, according to Tocqueville: "The crow is increasingly attempting to imitate the eagle!" After receiving a health warning, he takes a nap in Tocqueville and decides to write his autobiography. He is still a member of the General Council and was a strong supporter of building the Paris–Cherbourg railway, particularly when Louis Napoleon visited Cherbourg. He makes the decision to write what would become "The Old Regime and the Revolution" while on a short trip to Italy, close to Naples. On December 2, 1851, the anniversary of Napoleon I's coronation and the Austerlitz victory, a coup d'état took place. Tocqueville is one of the 220 lawmakers who gather at the 10th district town hall to vote to remove the president of the republic. He left politics after serving time in Vincennes prison and being later released.

V. Alexis de Tocqueville Death & Legacy

1. Where was Alexis de Tocqueville buried?

Alexis de Tocqueville died April 16, 1859 in Cannes. After a religious service, his body was taken to Paris and interred in the crypt of the Eglise de la Madeleine before being taken to the Normandy village of Tocqueville.

2. Alexis De Tocqueville's Legacy In The Early 21st Century

Never before has the legacy of Tocqueville been more apparent on both sides of the Atlantic, especially when one considers the number of European nations where the welfare state has reached its limits and is on the verge of going bankrupt. Politicians in these nations lack a long-term perspective on economic and societal priorities and frequently lack the leadership required to carry out the required reforms, which inhibits the innovation and vitality of civil society.

The four pillars of freedom, personal responsibility, humanism, and tolerance, as outlined by Alexis de Tocqueville, are essential for balancing individual growth and social existence. In the same vein, the Tocqueville Foundation holds that in order to strengthen the "social pact" and collective effectiveness for the benefit of all, it is necessary to inspire citizens, particularly students and young people, to participate and contribute their time, ideas, and money. This will instill in them the understanding that their personal well-being is correlated with the well-being of society as a whole.

Efficiency in the public interest does not require centralized public structures or a traditional "top down" strategy; on the contrary. The expanding and now global influence of social networks and significant private foundations, which represent a "bottom up" strategy for addressing societal issues and are significantly more innovative, adaptable, and practical in practice, serve as an example of this. Therefore, it is crucial to breathe life into the civil society and private sphere, which are all too frequently constrained by bureaucracy and the daily grind of the public sphere. We want to play a major role in this evolution toward a new citizenship, a more active citizenship, and a society in which everyone understands that they can influence collective destiny in a more practical and effective way than by casting a vote every time. Everyone in the technological world of today can make their voices heard, and our foundation, which is named with a brand known around the world to symbolize the values of freedom, individual responsibility, and humanism, wants to be a major player in this development.

In civil society, there are two different kinds of entities besides people: businesses and associations, or for-profit and nonprofit organizations. Corporations do not have borders, in contrast to governments. Investors and customers, who have complete freedom to purchase their goods or services, must be persuaded to do so. They might face consequences from market forces or legal action if they spend more money than they have available. Since associations (such as unions, foundations, or private associations) are largely subject to the same types of restrictions, the for-profit and non-profit sectors are actually becoming more and more interconnected as productive partners. Because it is in their best interest, as is generally acknowledged, and because associations can greatly benefit from the professionalism and expertise of businesses, companies want to be good corporate citizens. These discussions and collaborations benefit society as a whole. The Tocqueville Foundation's goal is to raise awareness of civil society, citizens, businesses, and associations about their capacity for action, and the leverage they currently have available for working in the public interest and helping the less fortunate, ultimately also serving their own individual self-interest. All of these groups are daily subjected to efficiency and good management constraints. Public authorities would regain momentum and legitimacy by relying on a stronger civil society and reducing their role, and as a result, would stand to gain significantly from this revolution.

VI. Alexis De Tocqueville Reputation

In the decade that followed his passing, as the major European powers adapted to universal suffrage, Tocqueville's stature in the 19th century reached its pinnacle. He passed away just as French liberalism was beginning to take off again. His nine-volume collection of works, which Beaumont edited between 1860 and 1966, was regarded as the legacy of a martyr for liberty. His name came up in discussions about the expansion of the franchise in England in the 1860s, and in discussions about federalization and liberalization in Germany in the years before Otto von Bismarck's empire. The posthumous publication of his Recollections in 1893 or the publication of his correspondence with his friend, the diplomatist and philosopher Arthur de Gobineau, did little to stem his influence's decline after 1870. By the turn of the century, he was all but forgotten, and most people considered his writings to be outmoded classics because they were too speculative and abstract for the generation that only trusted in proven knowledge. Furthermore, Tocqueville's prediction that democracy would be a powerful force that would level the world seemed to have failed because he failed to foresee the magnitude of the new inequalities and conflicts brought on by industrialization as well as those brought on by European nationalisms and imperialism. While the classless society had not materialized in Europe, America appeared to have done so by adopting a nationalist and imperialist mindset. Tocqueville's name was too closely linked in France to a limited liberal tradition that quickly faded away during the Third Republic. Although his work as a trailblazing historian was recognized, it is significant that American, English, and German scholarship played a significant role in the resurgence of his ideas and reputation as a political sociologist.

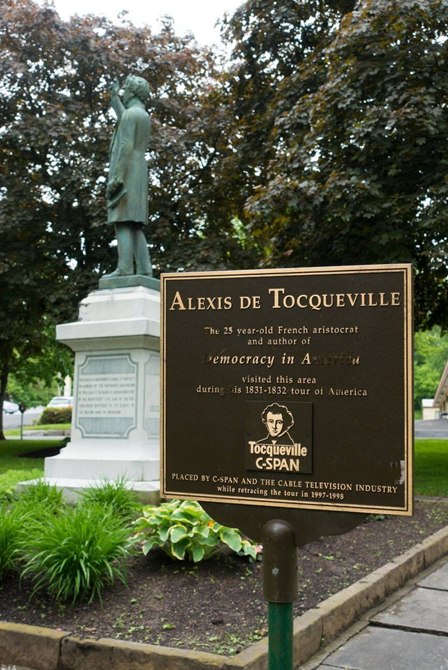

A "Tocqueville renaissance" was sparked by the totalitarian threat to liberal institutions in the 20th century brought on by the Great Depression of the 1930s and the two World Wars. The out-of-date information in his books didn't seem to matter as much as the political philosophy that underpinned his efforts to uphold liberty in public life and his methods for identifying latent social tendencies. His writings were found to contain a wealth of insightful sociological and philosophical hypotheses. Popular perceptions of Tocqueville as an alternative to Marx as a social change prophet in the West resulted from the revival of social democracy in Europe after 1945 and the polarization of the Cold War. Tocqueville experienced a surge in popularity, much like he did in the late 1850s and early 1860s, particularly in the 1990s in the United States, where his travels were retraced. Those who share Tocqueville's disdain for static authoritarian societies, as well as his conviction that class distinctions will eventually vanish and that liberty is the highest political value, are likely to continue to look to him as an authority and an inspiration.

VII. 10 Facts about Alexis De Tocqueville

- In his lifetime, Tocqueville held a number of government positions. In the National Assembly and the Chamber of Deputies (1839–1848), he represented Manche, the hometown of his family (1848-1851). In addition, from June to October 1849, he briefly served as the national government's minister of foreign affairs.

- Beginning on May 9, 1831, the King of France granted Tocqueville a nine-month visa to travel throughout the United States. His official task was to research the American criminal justice system.

- Gustave de Beaumont accompanied Tocqueville on his journey.

- Tocqueville spent the majority of his time touring small towns and rural areas in the United States and Canada, though he did visit a few prisons.

- In a few passages, Tocqueville showed a fair amount of foresight. "To the south, the Union has one point of contact with the Mexican Empire, where one day serious wars may well develop," Tocqueville wrote about Mexico in volume I, part 1, chapter 8.

- Tocqueville supported democracy because he believed it promoted equality, but he also understood that, if not managed carefully, it could result in less freedom.

- The concepts of Tocqueville are timeless and frequently interpretable. On the campaign trail and when trying to pass legislation, both Republicans and Democrats, Liberals and Conservatives still cite Tocqueville.

- Tocqueville was right about some things that happened in America, but he was wrong about the Civil War, which was arguably the most significant thing that ever happened in American history. In Chapter 10 of Volume 1, Part 2, He wrote: "It would be challenging to demonstrate that one of these states could not do so if it wanted to remove its name from the contract today. The federal government would be unable to override it in any obvious way by relying on either force of law."

- At age 59, Tocqueville passed away from tuberculosis in Cannes, France, on April 16, 1859. He was laid to rest in Normandy at his family's graveyard.

- The comte de Tocqueville, Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, was born into an old aristocratic family. Due to the overthrow of Maximilien Robespierre, his father, an officer of the King Louis XVI's Constitutional Guard, narrowly avoided being put to death by guillotine.

WHAT IS YOUR IQ?

This IQ Test will help you test your IQ accurately

Maybe you are interested