Peculiarities of Cyberspace

Virtual community | Not a second-hand world | Networks of the future | Quantity creates quality | Community | Face-to-face or CMC? | P2P: networks of unknown friends | Flash Mobs | Second Life | Online morality and decency

Hypertextual Revolution | The future of the semantic web

Communicating on internet | E-mail: use & abuse of electronic messages

Anthropology of the Internet A stateless society? | Simple questions

Internet Use(rs) Cybergeography | International | U.S.A. | Europe | Netherlands | Closing digital divides

Cyber Capitalism A land without scarcity | Liberty or Equality in Cyberspace | Internet Shake-out? | Search Engines | Providers | A new colonial war?

Learning at Distance Educational revolution | Learning in your own time | Learning & teaching styles | Net-Students learn better | Learning without frontiers | Telecoaching

NetLove & Cybersex Intimate at a distance | Bodiless intimacy | Eroticizing virtual reality | Virtual & local relations | Netlove | Pornography in Cyberspace | Child Pornography | Regulation of Cyberporno | CyberStalking

Politics Egypt: Facebook Revolution?

Cyberterrorism Jihad in the Netherlands | Jihadists running Wild(ers)

Death & Mourning Immortal in the web | Virtual graveyard | Virtual mourning groups

Introduction

|

"A complaint from a client is a gift from heaven."

[Entrepeneur] |

Choice of subject

This thesis focuses on the importance of the role of the teacher as a telecoach in online learning processes. It is my final project for the post-academic MSc training 'Telematics Applications in Education and Training' at the University of Twente (Faculty of Educational Science and Technology). This training is described in detail in the empirical part of this thesis. Yet, not only the content of the training is described but also coaching within the training, since that is the subject of my research project.

I have chosen telecoaching as my main research subject from two angles:

- my background as a teacher of English and student counsellor in regular, secondary education;

- my experiences as a student in this experimental online training.

When I was a teacher of English at a secondary school somewhere in Holland I did my utmost to be a good coach for my pupils. I have experienced that many students benefit enormously from good coaching by their teachers. Most students greatly appreciate a personal approach, the 'human touch'. Personal attention for and help with their study problems is likely to increase their motivation and often their results. Unfortunately quite a few teachers do not endorse this view or simply aren't capable of providing good supervision or coaching or don't consider it to be important.

Another reason for pursuing this subject is that I study Telematics Applications in Education and Training [TAET] at the University of Twente. It is a one-year experimental study, fully at a distance - apart from a few face-to-face meetings on-campus - and subsidised by the European Social Fund. My role has changed now: from being a teacher and coach in the face-to-face delivery mode I have become an online distance student, experiencing telecoaching for the first time in my life. Both roles have an impact on my view of telecoaching.

Telecoaching is a relatively new field of expertise. This means that we only have limited experiences and evaluations of these experiences of telelearners. It also means that there are very few differentiated and tested models for telecoaching. The particularities of telecoaching are still mainly weighed against the defining characteristics of conventional, formal lecturing styles. Telecoaching is still looking for its own form. Yet, there are some basic characteristics and possible features that we can identify. When we put these bits and pieces together - which I tried in this study - a remarkable picture arises. It is a picture of a completely transformed educational principle and practice. We have just started to experiment with telecoaching, and it is amazing to see the speed at which the practice and theory of telecoaching progresses.

In an online educational programme, in which there is hardly any face-to-face contact with instructors, different demands are made on coaching, both in the instructional and the interactive or communicative sense. Coaching is important in any field or form of education. In my view coaching in distance educational programmes is even more important and requires specific strategies and skills [Mason & Weller 2000, Prendergast 2000]. Coaching has to be organised in such a way that asynchronous learning can take place in a fruitful way. In this research project I will try to present a clear view on the essentials en peculiarities of telecoaching.

Research question and general design of the study

My final project consists of an analysis of our TAET programme as to coaching aspects. The main research question in this thesis is: what activities and roles of coaches have an impact on the learning process as well as on the development of a learning community? This general question can be divided into two subquestions:

- What are the activities of coaches that stimulate and moderate self-reflective learning practices?

- To which extent and in which forms has a learning community been developed in the course?

In the next section I have outlined the theoretical background of this project: Telecoaching in Theory. I analyse the main characteristics of and problems involved in the process of telecoaching. This results in an analytical framework for the evaluation of telelearing: Evaluating Telelearning. This second section also describes the project in question as a qualitative research project, that makes use of webbased questionnaires for students and teachers, supplemented by expert interviews. A description of the electronic learning environment, TeleTOP, will be included and course documents and communication tools are consulted for further information.To top it off, interviews with coaching 'experts' of the Open University (Heerlen) will be included to make some comparisons and to illustrate certain conclusions. In the third section I present the results of my empirical research, starting with a description of the TAET course: Empirical Results. In the fourth and last section Conclusions and Recommendations are drawn based upon the empirical results and expert consultations.

Next to these four main sections, and apart from the list of used Literature, my thesis contains several other related documents. In four annexes I elaborate on themes such as the meaning of Hypertextual Skywriting for non-linear learning processes, the importance of clearly organised Navigation Structures in educational sites, some principles and pros & cons of Web Design in online courses.

In the last annex I have written A Personal View. I was a participant in this course myself so I was able to combine empirical results with 'a view from within'. But this also made it sometimes hard to make a clear distinction between the results of my empirical research and my personal experiences and views. To smoothen this process of tearing myself apart, I stored my strictly personal experiences, views and criticism in a separate document.

It should be emphasised that my research project is not focused on the design of a new instructional model for this training (design of an effective training strategy, information presentation and so on). It is primarily directed at tracing the problems connected with online coaching and learning and provides suggestions for improvements. In my theoretical framework I have held on to this problem-directed approach, without any pretension of a 'systematic theory'. That is why I call it 'telecoaching in theory' and not 'theory of telecoaching'. In the empirical and conclusive chapters I have followed a similar logic: tracing literature on the problems involved in telecoaching and telelearning, designing an analytical framework for the evaluation of telelearning, and collecting and processing data according to this analytical framework.

In this study I will use the terms online learning, distance education, webbased learning and telelearning more or less indiscriminately, although I know they cannot be equalled. When I use these terms I refer to educational programmes that are to a great extent delivered through the internet. When I refer to telecoaching I mean teachers' support in instruction and communication within virtual learning environments. When I use the term traditional education this refers to frontal or formal educational practices that are described in the section in which I make a comparison between non-linear telelearning and traditional learning. To enlarge the contrast I only present a simplified - and perhaps even exaggerated - picture of the traditional education practices and the frontal style of teaching.

Writing this thesis has been a wonderful, instructive and fascinating experience. When I started the project I realised that - as a researcher and participant of the training - it was of the utmost importance to remain as objective as possible. Writing a webbased thesis made it easy for me to let different people (students and teachers) read parts of it in different phases of its development. This was tremendously stimulating and I am very grateful to quite a number of people.

First of all I would like to thank my mentor, Hans van der Meij. With his critical remarks he helped me structure my ideas, gave me a lot of food for thought, and most importantly urged me to make my own choices in my research. In times of severe insecurity his kind and constructive reactions helped me to overcome my fears.

Secondly, my external mentor, Albert Benschop, who patiently and - foremost - lovingly supported me during the whole training. As my private tutor, living only one floor below, he helped me enormously to structure my learning experience and never let me down when I almost lost my nerves.

I thank all the TAET teachers who took the time to fill out my questionnaire, and especially Wim de Boer, Alfons ten Brummelhuis and Tim de Jong who gave their comments on the first draft of the empirical results. They patiently and critically read the text and discussed omissions and disputable issues with me at length. With my two mentors they gave me the self-confidence to go on with my work.

I also thank Willibrord Huisman, Marcel van der Klink and Wil Verreck who gave me the opportunity to look behind the scenes of the Open University (Heerlen), and the other experts of the Open University who gave me their professional views on some complex coaching issues. Ton Korver (Katholieke Universiteit Brabant) was so kind to critically read this thesis and to draw my attention to some important but still sketchy telecoaching issues. With Frans Jacobs (Hogeschool Maastricht) I developed a mutual distant bond of support and I thank him for his efforts to find an apprenticeship and for the attentive reading of my work.

I am also very grateful to my friends and relatives who had to put up with me during this year and all the time showed their belief in my abilities.

Last but not least: during the whole training and while writing this thesis my fellow students have been of great support, most of all Sylvia Walsarie Wolff, who zipped me up daily with her cheerful and inspiring emails. Without their help and unrestricted stimulation I couldn't have finished the TAET course and I certainly couldn't have realised this research project. And this counts for all the people mentioned here.

And now all the others are saying, "What about Us?"

So perhaps the best thing to do is to stop writing Introductions and get on with the Book."

[A.A. Milne, 'The World of Pooh']

TeleCoaching in Theory

Structuring Telelearning

Learning at a distance

In traditional education (be it secondary or higher education) pupils or students and teachers come together in a classroom or lecture-hall at the same time. The teacher takes place in front of the class and starts telling and teaching. The students are expected to pay attention, take notes, and do exercises on the spot. An essential characteristic of this type of education is that almost everything is learnt by means of teaching. This type of education is often not very effective: there is hardly any check if students really pay attention or if they have really understood what is being taught. Much subject matter seems superfluous or irrelevant to students [Benschop 1996-2000; personal experience and communication with ex-students]. Although students and teachers are physically present in the same room, the question is whether they really make use of their communication possibilities. More often than not students are afraid to ask questions. More often than not there is no room for extensive discussions (unless this is incorporated in a lesson). The students depend on their teachers as to the structuring and the content of the classes.

The rise of modern internet and telecommunication technologies makes it possible to change traditional education radically and to create webbased distance education of high quality. The communication between students and teachers and among students that is required for a fruitful learning process is not confined to the physical classroom any more. More and more educational institutions offer distance education courses, especially in higher education. Teaching and discussing topics can nowadays be realised in more or less completely virtual learning environments that facilitate all forms of synchronous and asynchronous communication, and utilise videoconferencing techniques.

Distance education, however, is not the same as 'learning at a distance'. In nearly all definitions of distance education lies the presupposition that the basis for learning is that there is someone who teaches.

"Distance education is planned learning that normally occurs in a different place from teaching and as a result requires special techniques of course design, special instructional techniques, special methods of communication by electronic and other technology, as well as special organisational and administrative arrangements" [Moore & Kearsley 1996].

Although the emphasis in this definition lies on learning it is assumed that education is a service offered to students instead of a self-directed learning process.

'Learning at a distance' places learning and the learner at the centre of the learning process. The learners are the creators of their own learning process, making use of modern communication technologies which enable them to search for the most relevant sources of knowledge. 'Learning at a distance' facilitates learning processes that are non-directive, interactive and creative. Learning styles and teaching styles will need to change in four directions:

- A shift from frontal education ('klassikaal onderwijs') to computer-mediated access to educational resources;

- A shift from the student as a passive receiver of education to a learning process that is student-centered;

- A shift from individual learning to a new balance of individual and collaborative learning; and

- A shift from homogeneous and stabilised learning content to a fast changing content that is presented in different forms and formats [Benschop 1996-2000].

Taken these points together we can say that we are moving into the direction of a student-centred approach of education that generates a higher degree of learning autonomy.

Traditional face-to-face learning versus non-linear webbased learning

In traditional learning processes people are taught subjects in a linear way, with few side-steps permitted, and this only depending on the flexibility of the instructor. Often it is a non-flexible and sometimes even boring way of both teaching and learning. I have experienced this very often myself, e.g. while giving a lecture on English literary history. It deprives learners of the possibility to work and learn according to their own pace, associations and interests. Traditional learning processes are prescriptive: authors of coursebooks and teachers dictate the path the learners are to follow. After the coursebook and the teacher have decided that a subject has been covered, the learners have to submit a test and the next subject has to be tackled. The test is usually the teacher's only check to see if a learner has mastered the subject or not. However, a sufficient mark doesn't guarantee in any way that the learner has grasped the subject. A sufficient mark can, for example, have been reached by cheating or by learning certain aspects of the subject matter by heart. Usually, if a test has been 'rewarded' by an insufficient mark, the test doesn't have to be redone, at least not in secondary education. The mark is compensated by other components of the subject. The learner usually has no opportunity to correct mistakes and submit the work again.

Let's take a traditional English grammar course as an example. This type of course usually consists of a large set of grammatical items, such as the definite and indefinite articles, adjectives, adverbs, word order, and so on. These items are ordered and taught in a specific way over the years. In the grammar books available in Holland the first graders usually start with the use of the present continuous in English, followed by the simple present. Each grammatical item is accompanied by exercises: filling in the right grammatical forms or translating sentences from Dutch into English. And this goes on and on. From present continuous to simple present to simple past to present perfect and so on. The course books usually offer no possibilities for diversions. This also counts for integrated courses, in which grammar is not taught separately, but in a textual context of certain British events. Here text, vocabulary, grammar, listening practice and exercises are integrated in chapters, but the only diversion consists of the different items, not of the different directions that can be taken. When a grammatical item has been covered according to the teacher's standards, a test is submitted. If it turns out to be a very complex item, it is up to the teacher to decide whether to elaborate on it and give some extra exercises before the test is submitted. Again, in this specific case, a sufficient mark doesn't have to mean that the subject matter is understood.

Student who has just taken a non-linear course.

|

Non-linear learning is not the mirror opposite of linear learning in the sense that it is completely non-directive or not focused on a more or less well-defined field or level of knowledge. Non-linear education does not prescribe but structures the learning experiences: Non-linear courses determine the boundaries in which learning behaviour can vary, and within these boundaries the chance that specific learning trajectories are actually followed.

This general proposition has some specific implications for the design of the learning process. Learning processes should always be: (a) organised around a specific problem or cluster of problems; (b) demarcated in terms of levels of complexity and/or abstraction; (c) structured by the educational material that has been embedded in a virtual learning environment, and last not but least (d) guided by a knowledgeable and sensible educator or coach [Benschop, personal communication]. In this study I will concentrate on the last point.

An illustration of the differences may be two perceptions of how to offer history as a subject. In a traditional learning process the world's history is usually presented in a chronological (and often quite factual) way, which may lead people to believe that historical events are not related. Or, that history is established in a such a deterministic way that there is no room for critical questions like: why have historic events taken the course they have taken, if they could also have taken another course? A non-traditional presentation of history would allow people to relate historical events to each other according to their own interests and to go back and forth in history

Objectivist versus Constructivist Learning Perspectives

When we want to teach somebody, we have to know what learning means and how students expand and enrich their knowledge. It seems that the academic educators can be split in two groups with different, mutually excluding visions on learning as a cognitive or knowledge process: the objectivist and the constructivist perspectives.

|

Benefits of the objectivist stance

The objectivist perspective on learning and the related objective-rational instructional design model has often been criticised from the opposite, constructivist point of view [Spiro et al. 1991; Willis 1995; Tam 2000]. Therefore it might seem to be 'cursing in your own church' to pose the question if the objectivist stance has any benefits at all.One of the basic characteristics of the objectivist approach is that the learning and instruction process are sequential and linear. For both students and teachers this seems to be the most 'natural' way of working. Every part of the learning process is organised in a simple consequential order. Linear education consists of units (paragraphs, pages, articles, books) which are connected to the preceding or the following unit in a straight line from beginning to end. Students just have to follow this line and will never have to ask themselves: "What would I like to read next?" Linear education looks very much like a prearranged trip in which the whole trip and excursions are planned beforehand in a certain order by the travel agency. Students seldom 'get lost in linearity'. The greatest benefit of the objectivist stance is that this kind of education is well-embedded in the traditional (linear) way of thinking and literacy.

A serious weakness of the objectivist stance has been the lack of detailed instructional models for training complex cognitive skills. But the benefit of some recent 'instructional design models' is that they usually are strong in analysing the recurrent and non-recurrent complex cognitive skills that can lead to '(self)reflective expertise' and increased performance on transfer tasks [see for instance Merriënboer e.o. 1997]. This is especially important in a situation where there is an increasing need for effective strategies and guidelines for the training of intensive problem-solving cognitive skills.

|

There might be some good arguments to build a 'third way' between the two polarised perspectives that dominated the educational debate for so long. In this transformational perspective non-linear education does not prescribe but structures the learning experiences. Teachers can only determine the boundaries in which learning behaviour of students can vary, and within these boundaries the chance (or structural probability) that specific learning trajectories and structures are actually followed. But teachers don't determine the specific learning trajectories or outcomes of individual students. Students have the freedom to bring their preferences and choices into the individual learning processes. They have to learn (i) how to determine and develop their own learning trajectory, (ii) how to participate in knowledge networks, and (iii) how to contribute to the 'open sources' development within the academic world. The measurement of progression in learning will be concentrated on the valuation of the results of assignments. Although peer assessment will become increasingly important, teachers will not be freed of the obligation to qualify the final result.

Learning processes should always be structured by a problematic situation or context that is central to the learning process. This is emphasised in the constructive theory tradition. The learning environment should adapt to and stimulate the learner's interest in solving puzzles (like many people are interested in solving crosswords or riddles). Essential is also that education and training take place in a collaborative situation in which the learner can make meaningful connections between prior knowledge, new knowledge and learning processes. Hypertext and webbased learning can facilitate finding these connections.

From a transformational point of view there are two central characteristics in the learning process: (a) solving of meaningful, relevant and realistically complex problems and (b) learning through interaction with others [Tam 2000]. "It is through communication with others that learners construct meaning from their experiences" [Miller & Miller 1999]. This implies a close cooperation between students and teachers and among students. It also implies that teachers no longer function as instructors but more as guides or facilitators, participating with their students in solving meaningful and realistic problems. Thus, both knowledge, authority and responsibility are shared among teachers and students. Students are no longer the 'empty barrels' into which knowledge can be poured.

What might be the consequences of these general deliberations for the learning goals and design principles of online learning processes? In webbased education I would define the general learning goals as follows:

Present a problem-solving situation in a - virtually reconstructed - realistic context: "right to work on interesting problems".

|

Rights and Obligations

It goes without saying that this list of 'rights' should be completed with a similar list of obligations. Obligations of teleteachers toward their students (such as to give good feedback within a reasonable time-span) and vice versa (such as student obligation to participate in the online learning community and to correct their failures). At the same time it should not be forgotten that teachers also have their rights (such as the right to the final grading or qualification of students' products).

|

- Provide opportunities for learners to collaboratively construct knowledge based on multiple perspectives, discussion and reflection: "right to cooperate with colleagues".

- Provide opportunities for learners to articulate and revise their thinking in order to insure the accuracy of knowledge construction: "right to make and correct failures".

- Create opportunities for the instructor to coach and facilitate construction of student knowledge: "right to have intensive telecoaching".

For each goal communication and information strategies and practices can be defined. The teacher has to arrange learning elements (learner navigation, access to information, self-tests, assignments etc.) to structure the learning process and the students' construction of knowledge [Miller & Miller 1999; Benschop 2000; Salmon 2000:32-35;141-2]. In this study I will concentrate on the last learning goal.

The transformational perspective has some determinate implications for non-linear instructional design that deviate from traditional instructional design:

- The traditional design process is sequential and linear: design, production/development, implementation and maintenance/revision. In the tranformational view the instructional design process is recursive, non-linear, complex and probably chaotic.

- Traditional instructional designers tend to break down content into component parts. In the transformational view designers tend to avoid this and try to construct environments in which knowledge skill, and complexity exist naturally. No more cutting of content into small pieces.

- In traditional design the goal is delivery of preselected knowledge. In transformational design the instructional goals evolve as learning progresses.

- While traditional designers tend to reduce the level of complexity transformational designers are building learning environments that facilitate the mastery of complexity in understanding by fully exploiting the hypertextual and multimedial repertoire [see below].

The design should be such as to provide learners with a rich learning environment in which they receive relevant information and guidance and in which they can learn how to build their self-regulated learning process [Willis 1995; Tam 2000]. I've elaborated on this theme on two special pages: Navigation Structures and Web Design.

Cognitive Flexibility

The Web environment, because of its associative, hyperlinking and non-linear features, is well-suited for the support of non-linear learning [Miller & Miller 1999]. Good web-design is of major concern for this kind of learning. The Cognitive Flexibility Theory (CFT) offers a framework for how to design well-navigable web sites [Spiro et al. 1991].

|

"Everything should be made

as simple as possible,

but not simpler"

[Albert Einstein].

|

Within the transformational perspective a theory of learning and instruction is emerging that has strong family resemblances with the cognitive flexibility theory: it emphasises the real world complexity and ill-structuredness of many knowledge domains. Many domains rather look like a 'patchwork quilt of competing concepts and methodologies' than a 'system of systematised knowledge'. Ill-structured knowledge is evident where: (i) each case involves multiple conceptual structures (multiple schemes, perspectives, organisational principles) each of which is individually complex; and (ii) the pattern of conceptual incidence and interaction varies considerably across cases of the same type: the domain involves cross-case irregularity [Cronin 1997].

Ill-structured knowledge domains are for example medicine, history, sociology and literary interpretation. Learning deficiencies due to subject complexity and irregularity can be remedied by means of learning processes that allow for greater cognitive flexibility.

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to:

- represent knowledge from different conceptual, methodological and case perspectives;

- represent knowledge at different levels of thematic specification or units of analysis;

- represent knowledge on different levels of hierarchically ordered levels of complexity or abstraction;

- transfer acquired knowledge to different problem-solving situations. [see also: Spiro et al. 1991]

This includes approaching problems from different conceptual viewpoints at different stages of problem solving at different stages of learning within the advanced knowledge acquisition stage [Cronin 1997]. This should lead to mastery of complex knowledge and transfer of complex knowledge.

In order to gain cognitive flexibility, flexible learning environments have to be designed in which the same items of knowledge are presented and learned in a variety of ways and from different perspectives. The computer, by its nature, is ideal for stimulating cognitive flexibility in ill-structured domains, especially because of its multidimensional and non-linear hypertext systems. Hypertext systems offer possibilities of non-linear and multidimensional traversal of complex subject matter, returning to the same place on the conceptual landscape on different occasions, coming from different directions. Learners have control, or rather should be offered the possibilities to have control to 'criss-cross' the instructional landscape in order to view subject matter from multiple perspectives [Spiro et al. 1991] and levels of complexity and/or abstraction. Multiple representations of complex subject matter and different levels of abstraction are required for full coverage of it. I've elaborated on this theme on a special page: Hypertextual Skywriting.

|

|

Analogies and metaphors are situated on 'the threshold of a concept' [G.W.F. Hegel]. They are like crutches: you'll finally have to walk without them. When the analogies and metaphors have done their work - preliminary organisation of complex phenomena - you can leave them for what they are and go on with the difficult task of defining scientific concepts. |

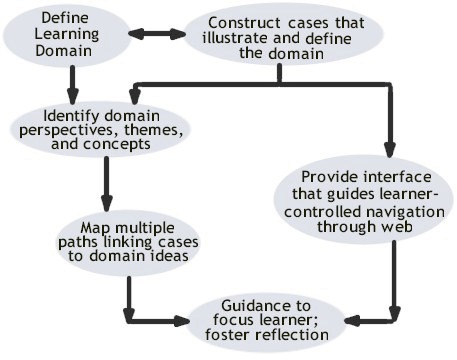

The general approach that is compatible with the transformational perspective is based on the steps represented in the next figure.

Risks of telelearning

From a transformational perspective learning in virtual environments seems to enable an almost perfect combination and balance of individualisation and collaboration, flexibility and structuring, articulation and reflection, complexity and transparency, non-linearity and recursiveness, that are all contributing to a stimulating and progressive student-centred learning process. But the balance between all these elements was always hard to find, and we are just passing the threshold of building and using the first generation of virtual learning environments. So we will be confronted with some old problems in substantial new contexts, and with some new risks that are immanent to all virtual learning environments. And therefore we must not be surprised to hear some objections against telearning. The three most heard of objections against telelearning are: (a) anonymity, (b) a too strong individualisation, and (c) increase in social distance between students and teachers.

- Anonymity

It has become a non-argumentative statement that learning in a virtual environment will inevitably lead to a situation where students lose their personal identity and will suffer from their anonymity. The assumption of this statement is that people can only gain a sense of personal identity when they meet each other face-to-face. Computer-mediated communication (CMC) however, seems to make this traditional condition of co-presence obsolete: personal relations and networks of social relations do not necessarily presuppose physical presence in one place anymore. Personal interactions that in earlier days took place in one room, will be more and more mediated by computers. Social interaction and communication can be digitally replicated. This is possible now because the current generation of computer and telecommunication technologies allow us to duplicate almost all the cues we use in personal communication: text, sounds, pictures, movies, and even smell and - still very primitive - tactile experiences. So (the sense of) anonymity might be a transitional problem that will be solved (i) when we will get access to fully multimedial computers that are embedded in fast and reliable global networks, (ii) when we will get used to and skilled in working with these new technologies, and last but not least, (iii) when we get used to completely new - virtual - forms of personal communication and interaction. And therefore we must be realistic and say: at this moment, in this phase of learning how to live and behave in virtual environments there is a risk of anonymity. We know that some students prefer to remain anonymous and perform well in contributing to online discussions. But others become inhibited because of this feeling of anonymity. These complaints should be taken seriously. Instructors or tutors can do something about this, for example by eliciting simple social contributions in the beginning [Salmon 2000].

- Individualisation

ln fully virtual learning processes a student is only connected to teachers and other students by wire. This does not necessarily mean that students are 'on their own', because virtual learning environments provide a whole range of synchronous and asynchronous forms of communication that facilitate collaborative learning processes. In ill-structured virtualisation experiments that try to copy the classical form of linear learning students will almost certainly have the experience of a much too strong individualisation that is not balanced by collective and collaborative learning activities. On the other hand online learning has to give room to acquire 'deep understanding' including the quiet to read, write and think on your own. This can best be realised with asynchronous forms of communication.

- Social Distance

The real challenge of telelearning is implied in this question: how can 'distance learning' in a virtual learning environment narrow the social distance between teachers and students? The conventional 'frontal' style of teaching has always created a social gap between the ex-cathedra speaking teacher and the students as a passive, listening audience. Learning 'at a physical distance' does not necessarily imply that this social gap will be deeper. On the contrary, the variety of communication and interaction tools that are embedded in webbased learning environments can be used to reduce the social distance between teachers and students. But this will only happen when teachers and students are able to fully use the interactive potential of webbased learning processes. Most current forms of online learning look like 'broken windows' that reflect both the obstinacy of the frontal style of teaching and the laborious attempts to discover and use the interactive potential of synchronous and asynchronous forms of online communication. In this transitional phase students might easily get the impression that their teachers have retreated behind an electronic wall and that there are no new interactive places where they can meet at a more or less equal level. Complaints about increasing social distance between students and teachers have to be taken seriously. At least they indicate that it takes time and effort to realise the social-interactive potential of computer-mediated communication in learning processes.

|

A synchronous class is a live broadcast event. For many educational organisations, synchronous webbased training is the 'killer application' that balances their self-paced online learning with the benefits of classroom instruction. But how can we determine when it's appropriate to use synchronous forms of webbased training. Synchronous tools make sense when (i) real-time interaction with tutors or subject-matter experts is critical; (ii) face-to-face interaction is not critical; (iii) the students are geographically dispersed. A synchronous technology — instructor-directed or student-directed and conducted in real time — can be implemented to supplement self-paced webbased training or to realise a telementoring programme. Jennifer Hofmann[Jan, 2000] has made a useful compilation of the capabilities found in synchronous learning applications. Synchronous features include:

Not one product currently encompasses all these capabilities, and not one capability is universal in the sense that it demonstrates the diversity of synchronous products. |

Peculiarities of Telecoaching

Prerequisite skills of coaches/teachers

Relatively little is known about what an instructor should know to be a good coach or facilitator. There are some guidelines to scaffold students learning electronically: for instruction, offering feedback, asking questions, structuring meaningful tasks, etc. [Bonks e.a. 2000]. But these guidelines are only a first step. It is crucial that the role of the teacher be redefined.

|

The Open University Business School has developed online training for around 300 of their tutors. "We believed that the tutors needed to be exposed, in a real but risk-free online environment, both to the software and to the way learning can be developed online before they themselves assumed the role of moderator" [Salmon G., Developing learning through effective online moderation, Active Learning 9: 3-8 (1998)].

|

In online learning processes the teacher will be introduced in a different way than in regular education. Teachers who want to gain their students' confidence will have to present themselves in a very distinct and open way. Moreover, and more importantly, teachers will have to be trained thoroughly to be able to operate in online learning processes. Tutors (or teachers) have to be trained for this purpose in 5 different stages [Salmon 1998:25-37]:

- Access and motivation

A stage in which the tutors are supported in gaining access to the virtual learning environment. Tutors must be able to ensure that the students are welcomed and motivated and to point to sources of help in gaining access to the learning environment.

- Online socialisation

A stage in which the tutors learn to take part in the online learning community. Tutors must be able to build bridges to ensure that the students make the successful transition from operating in the familiar face-to-face learning world to the new virtual environment of learning online. A key feature of online learning is that it is interactive and collaborative. The role of the tutor is that of enabling effective and purposeful collaboration.

- Information giving and receiving

A stage in which the tutor learns to find his or her way in the huge amount of information that is available. Tutors must be able to act as research leader and supporter in assisting the user in identifying and finding the information he or she really wants. Reference point: "If you don't know where you are going, then any road will take you there" [Alice in Wonderland].

- Knowledge construction

A stage in which they learn how to make use of interaction in order to create a new cognitive process. Tutors and students must learn to work together to generate and make new meanings through their collaboration. Tutors must be able to provide stimulus and facilitate the process of interaction. "Knowledge construction occurs when students explore issues, take positions, discuss their positions in an argumentative format and reflect on and re-evaluate their positions" [Jonassen et al. 1995].

- Development

A stage in which the learner becomes independent online. Tutors must be able to provide encouragement and, if necessary, access to facilities to encourage the individual to continue his or her self-development through the medium. Tutors progressively withdraw as the students become more self-directed.

Mason & Weller [2000] suggest similar measures to prepare teachers for online teaching. Since teachers have new skills to learn and new working practices to adopt they need the help of experienced tutors and help with the use of technical issues (e.g. conferencing software). They could benefit from ready-made activities and support conferences (in which they receive help with building educational sites).

Need of additional skills

Although it is obvious that in quite a few respects online teaching is different from traditional face-to-face teaching, there is hardly any recognition of this fact yet and often there are no resources available to prepare teachers adequately. Staff members are often not properly prepared to undertake the tasks they have to perform with the use of the new medium. Teachers should be given the opportunity to experience online learning themselves. This will make them more aware of the problems their students will have and make them more supportive. Moreover, too often teachers have to develop online skills alone and in the process they will experience the same problems and frustrations as their students. They should be offered computer training to reduce computer anxiety [Prendergast 2000].

Prerequisite skills of students

In order to follow an online course successfully, students also have to develop several new skills that they don't need as much in face-to-face education. First of all, students have to get acquainted and comfortable with their computer and its possibilities. They have to know how to browse the web and find relevant information. Students have to become familiar with the electronic learning environment in which they learn and how to interact in conferences and group work [Mason & Weller, 2000].

All cases of online education studied made it clear that a certain level of technical skills is a first prerequisite for successful online studying. But these skills are usually developed during and not before the course, thus taking up a lot of the students' valuable course time. Novices in 'computerland' say that they spend much more time on an online course, especially in the beginning, due to having to learn these technical skills. Mason & Weller [2000] report that in one of their 1999 courses - due to a delay in course mailings - "computer novices did not have sufficient time to get comfortable using their PC before the course started." They wrote a booklet for the 2000 course to help make newcomers familiar with Windows, navigation and study skills, so they had about 2 months' time to prepare themselves. An online orientation course or training may help students understand the communication complexities of asynchronous text-based communication and provide them with competencies for learning with new media [Wegerif 1998]. Students new to computer-mediated communication need to feel comfortable in the new medium first. They should be trained and inducted first, preferably online to get the 'feel' [Salmon 2000].

Yet, not only technical computer skills are required in online learning. Since students do not have a 'physical' guide to steer them through a course, they have to create their own discipline and motivation to come to independent learning. They have to 'learn to learn'. In the 'learning to learn'-process in webbased environments Collis and Meeuwsen [1997] distinguish 5 different levels of skills and indicate the problems involved in acquiring these skills levels:

- Articulation and reflection

It is quite difficult for students to reach a 'proper' level of articulation and reflection due to the relative newness of webbased environments. Students have to deal with new concepts, learn a new language (computer-speech and network-jargon), and develop computer and network skills. Acquiring these skills usually take up so much of their reflection time that there's hardly any time left to reflect on their study material, let alone on their own performance (see also 5: self-evaluation). It also makes it difficult for students to articulate their problems.

- Planning skills

Also due to the newness of web environments realistic planning is difficult because students are not prepared for the technical problems they will encounter, do not know how much time these problems will take, or how long it will take to perform any other task to work properly with their computer.

- Study skills

While in traditional education students have a long period to acquire 'proper' study skills, they have to start anew in a webbased environment.·Students not only have to learn from webbased information, they also have to develop some new social competencies, such as "networking (building a close circle of people), team-working (collaborate and share knowledge) and dialoguing ('rid your minds of any preconceptions and listen to arguments with full attention and without trying to interject')" [Jacobs 2000]. Although these competencies can also be developed within a local and formal learning environment, in online learning processes they not only are much more critical ('strategic competencies') but they are also strongly facilitated by virtual learning environments.

- Finding and applying relevant examples and resources

This is a complex matter because so much material is available on the internet and students usually have to find their own way in a maze of information. Students have to learn how to search the internet: using virtual libraries, subject guides, search engines, meta search engines and special navigators. And students must learn how to evaluate the quality of online documents and information systems: using criteria such as accessibility, credibility, coverage, accuracy, currency and design.

- Self-evaluation

It is already difficult for instructors to support self-evaluation in traditional learning. In webbased education this will most certainly not be easier. The reason for this is that students engaged in virtual learning environments use so many different resources and take so many different learning paths. Therefore support of self-evaluation should be differentiated for several learning trajectories.

Monitoring the development of these skills and monitoring student progress is of the utmost importance, but is complex and time-consuming. It's not easy to monitor students' problems and their technical skills level, because they are easily embarrassed when they have problems with their PC, software and the learning environment. It's not easy to monitor students' cooperation and their individual and group progress.

A sense of social presence

Student surveys at the Open University UK from over nearly 30 years show that the support and guidance of a tutor is a crucial component in students' satisfaction with their learning experience. If there are no face-to-face meetings the tutor's quality as a good coach is of paramount importance if students' satisfaction and support is a serious goal [Mason & Weller 2000]. In webbased courses students should never be 'left on their own' with no support, direction or leadership. This is where the telecoach comes into the virtual classroom [Salmon 2000].

|

Early studies on CMC were based on the filtered-cues position. The medium internet was described as one bereft of social context cues. These cues define the social nature of the situation and the status of those present and include aspects of the physical environment, body language, and paralinguistic characteristics. Because these cues are largely filtered out in CMC, the internet has been described as a lean medium that is relatively anonymous. In more recent studies the benefits of online anonymity for teaching and learning have been stressed, such as increased equity and higher participation rates.

Without the cues that can sometimes obstruct contributions, otherwise quiet students might find a voice. Other authors have questioned the assumptions and research findings associated with the filtered-cues approach. From the perspective of social information processing, Walther [1996] has argued that CMC can be as deeply relational as face-to-face interaction. All that is required is sufficient time and message exchange. The narrow bandwith may at this time deny users non-verbal cues, but they adapt to the medium and use textual cues to form impressions of other. CMC not only provides for the interpersonal, but also for the hyperpersonal.

Hyperpersonal is a more intimate and socially desirable exchange than face-to-face interactions. According to Walther, the hyperpersonal nature of CMC is enhanced when long-term future interaction is anticipated and when no face-to-face relationship exists. In cyberspace people can construct impressions and present themselves without the interferences of environmental reality.

|

It goes without saying that telecoaching requires different skills than traditional coaching. In the absence of mutual physical presence and of physical cues the instructor has to resort to different strategies to guide the students. Quite often this lack of physical presence is regarded as one of the main objections against distance education, but it need not be. After all, the question is whether physical presence in a physical space is actually needed to develop a sense of co-presence. Goffman's classical definition of the condition of co-presence has been: "persons must sense that they are close enough to be perceived in whatever they are doing, including their experiencing of others and close enough to be perceived in this sensing of being perceived" [Goffmann 1963:8]. The question is whether you have to be in someone's physical proximity to experience being perceived in what you are doing.

-

"The combination of computer and telecommunication technologies has paved the way for a revolutionary compression of time and space. The acceleration of time and the contraction of space have created completely new possibilities for personal interaction and direct communication. Many forms of social interaction and communication can be mediated by computers which are connected to Internet. Computer-mediated communication (CMC) seems to make the traditional condition of copresence obsolete: personal relations and networks of social relations do not necessarily presuppose physical presence in one place anymore" [Benschop 1996-2000].

Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) is "the process by which people create, exchange, and perceive information using networked telecommunications systems (or non-networked computers) that facilitate encoding, transmitting, and decoding messages" [John December 2000]. Computer-mediated communication can certainly create a sense of social presence [Steinfort 1999; Benschop 1997-1998]. The essence of the social interaction is not the direct physical presence, but social presence, that is the ability of a communication medium to allow the group members to feel the presence of an actor with whom one can communicate interactively.

Teaching online and not being involved in face-to-face education may also have the advantage that teachers are not confronted with some aspects of physical copresence that most of them don't want to transfer into a digital environment, such as bored faces or other annoying aspects of some students that occur in local classrooms [Lucinda SanGiovanni, personal email].

Teaching in cyberspace has also given us a chance to (re)view the familiar in our educational practice, thereby using our life online to inform our face-to-face teaching. Debates about new educational technologies have led to a (re)viewing of pedagogy [Atkins 1991; Chester/Gwynne 1998].

A sense of accomplishment

Actually, in a webbased environment students have many more opportunities to communicate, to collaborate, to publish and correct their own work and to interact with their peers and teachers. And these new opportunities may be very rewarding for teachers as well [Collis & Meeuwsen 1997].

-

"Teaching, especially online teaching, provides an immediate sense of accomplishment and a means to exercise one's creativity" [Bonks et al. 2000].

In the physical classroom teachers often have to deal with a large group of students. In Dutch secondary education many classes consist of 30 pupils. Individual assistance in such large groups is nearly impossible or given outside of the regular classes. The largeness of the group and the teacher-centredness of face-to-face education makes extensive communication and collaboration almost impossible. Yet, if given the chance, students do communicate with each other, but most often about matters that are personal and have nothing to do with what is being dealt with in the lesson.

The added value of online learning is that instructors can offer their students more individual assistance, and can stimulate learning through collaboration. This will take up (much) more tutoring time, especially for the novice online teacher. This might be one of the most resistant obstacles for the future of telelearning. Especially because at the present time the staff is often not properly prepared to undertake the tasks they have to perform with the use of the new medium [Prendergast 2000]. Yet, spending extra time doesn't always have to be seen in a negative light, especially not when it can make the learning experience more meaningful [Mason & Weller 2000].

Distance education students often have different expectations than students in conventional education. Since they learn in a much more flexible learning environment and more often than not can work at their own pace they expect immediate feedback at the moment when they need it. For example if instructions are not clear, which asks for a prompt reply because otherwise students cannot continue with their work. In physical face-to-face situations the problem of ambiguous instructions and expectations can easily be solved. In asynchronous communication there may be a significant delay in the teacher's answering of the students' questions [Hara & Kling 2000]. This is a serious problem because teachers will never be available all the time. However, the necessity of explicit instruction and of timely feedback is taken very seriously in many studies, and it can save the teachers a lot of time and stress. Teachers and students should learn to manage their expectations about timely and effective communication. They must find the practical solutions that can create a balance between increased coaching expectations of students and the time limitations of teachers.

Frustrations in online learning

Until recently, most research on distance education emphasised its virtues and paid little or no attention to the difficulties students experienced [Hara & Kling 2000]. These researchers focused on distress: feelings of isolation, anxiety, confusion and panic in an online learning process. The original research question was on how students learnt to overcome their feelings of isolation in order to create a community of learning. It turned out that isolation wasn't the main problem. Frustration, confusion and anxiety were. There are two main sources of distress: (a) technical and technological problems due to lack of skills, (b) problems with course content and instructor's practices in managing the communications with students, and (c) problems with communication conventions and rules.

- Technical and technological problems concerned for example not being able to keep up in MOO field trips because of lack of knowledge of what to do, how to perform, or because intended commands didn't work. Lack of technical skills are mentioned in almost every study [Hara & Kling 2000, Wegerif 1998, Mason & Weller 2000, Salmon, 1998, Salmon 2000, Prendergast 2000, Rowntree 1995]. Another source of frustration is the lack of immediate technical assistance. Frustration can also be stimulated by unclear technical prerequisites: saying that no prior knowledge of HTML is needed, and having students build a website as one of the first assignments (this was also the case in our TAET training) .

- Students can get frustrated and confused when they have problems with course content, teachers' instructions and feedback. The case study of Hara & Kling demonstrate that most students get increasingly anxious due to ambiguous instructions of the teacher, lack of clarification of instructions and lack of teacher support. They usually stopped asking for clarifications after asking for a second time and again not understanding the explanation. Teachers often underestimate the problems the students are confronted with and have to be more explicit and specific in their assignments.

- Another source of frustrations is anxiety about communication or discourse conventions appropriate in class [Hara & Kling 2000; Wegerif 1998]. The barrier may be caused by the perception of differences in the use of language and style of contributions [Wegerif 1998: 8]. An overload of emails and attachments can cause distress, leading to falling behind in reading and responding online. If students have to perform procedural tasks, e.g. printing extensive study material from a WWW site, they also get annoyed [Collis & Gervedink Nijhuis 2000].

Yet, these negative experiences and frustrations can also be interpreted positively, to experience what your own students may experience when you start teaching online [student in Hara & Kling 2000, Frans Jacobs, personal communication].

How can a telecoach constitute and guide learning communities?

Cooperation is regarded to be of paramount importance to deepen understanding, sharpen judgement, and extend knowledge. Cooperative learning leads to higher achievement in almost all respects: the mastery and retention of material, the quality reasoning strategies, and the transfer of thus acquired knowledge to different situations [Jacobs 2000]. Therefore a positive attitude towards working cooperatively is essential for the success of online learning strategies that are student-centred.

|

"Because webbased environments offer non-linear navigation of hyperlinked resources, the student, in theory has at his or her fingertips not only all the materials of the course, but also a cyberlibrary of resources from all over the world, as well as contact possibilities with experts and fellow learners alike" [Collis & Meeuwsen 1997].

|

In a learning community, which is student-centred and collaborative, students can learn as much from each other, as from the course material as from the interactions with and interjections of their teachers. Collaborative learning can start with sharing difficulties going online and getting to know each other. "Forming a sense of community (...) seems to be a necessary step for collaborative learning" [Wegerif 1998]. Without this feeling of a community students can feel lonely, anxious, defensive, and so on. A learning community should be democratic, respectful, open to challenges, and so forth. Instructors can help create a community of learning, students can help themselves as well as the others, by supporting them. Two-way technology allows for interactions among students and between students and teachers and can thus support this sense of a community [Hara & Kling 2000].

What students learn in such a community is not so much product as process. They can develop their own creative cognitive process of contributing ideas, having them criticised or expanded on, giving them the chance to reshape them or abandon them in the light of peer discussion. The learning becomes not only merely active, but also interactive. Students cannot only turn to others to ask for an answer to their questions or a reaction to a new idea, but also can turn to others to comment on their ideas [Rowntree 1995]. Careful planning of online discussions have to be part of the guidance of this process.

Yet, becoming a well-functioning member of a learning community doesn't always go without saying and can be troublesome for some people. In his study on the social dimensions of online learning Rupert Wegerif argues that a 'proper membership' of a learning community is preceded by the process of changing from 'outsider' to 'insider' in the community. Individual success or failure of the course depends upon the extent to which students are able to cross a threshold from feeling like outsiders to feeling like insiders. When learning is considered as socially situated it is also "a process of becoming part of a community of practice" [Wegerif]. Telecoaches have to support students in crossing the threshold from outsider to insider. In order to achieve that students behave as 'proper and proud members' of a learning community telecoaches first have to introduce them in this community.

Successful support of learning is achieved when students can participate in the practices of the community and can move from the 'side' to the centre in an easy way. This feeling of becoming part of a group or learning community can be blocked by (a) lack of access and therefore problems with submitting contributions, (b) lack of technical skills, (c) lack of self-confidence, (d) lack of time, (e) unfamiliarity with the proper discourse, (f) an 'ignorant' moderator who is unaware of these problems.

The main task of telecoaches is to help students to become involved in various forms of 'virtual dialogue', so as to enable them to become more actively involved with subject and material, to help them relate to previous knowledge and personal experience, and to become a builder of an online learning community.

That's where the art comes in...

In this study I analyse the main characteristics of and problems involved in telecoaching against the background of a transformational perspective on non-linear learning processes. In this perspective the main task of teachers is to structure the learning experience of students. Teacher don't prescribe the learning path nor the outcome of learning processes — they only determine the boundaries in which learning behaviour of students can vary. This student-centred approach is exemplified in some general instructional goals for webbased education. In the new virtual learning environments students can claim the right to work on interesting problems, to make and correct their failures, to collaborate with other students, and last but not least: to receive intensive telecoaching. The main goal of non-linear learning processes in virtual environments is to develop and cultivate cognitive flexibility that leads to a mastery and transfer of complex knowledge.

Apart from some transitional problems - such as anonymity and social isolation - the main obstacle for a successful application of the new non-linear learning principles seems to be the intensity and flexibility of telecoaching. We have seen that distance education students often have different expectations from coaches than students in conventional education. Because they operate in a much more flexible learning environment and can work at their own pace they expect immediate feedback at the moment when they need it. It seems that the introduction of tele-education generates a growing need for telecoaching. This 'revolution of the rising telecoaching expectations' puts telecoaches under very high pressure. Even in cases in which telecoaches are well-prepared for their instructional tasks, they are always in danger to fall short of the coaching expectations of their students. Webbased telelearning can be timesaving in many respects, but certainly not in the domain of telecoaching.

Telecoaching has opened a new branch of expertise in the educational sciences. There are only a few systematic evaluations of these experiences with telecoaching. And we don't have any serious models for telecoaching which have been tested in the field. Attempts in this direction are mainly focused on the differences between coaching in conventional, formal education and in telelearning settings. Telecoaching is still looking for its own form. Starting from the transformational perspective on education I have identified the basic characteristics and possible futures of telecoaching. We witness the beginning of a revolutionary transformation of educational principles and practices. And it is good to see that the practice and theory of telecoaching is progressing at high speed. The informational revolution thunders past all educational tracks — not to be run down by it, that's where the art comes in.

Evaluating Telelearning

Analytical Framework

In the previous chapter we have seen that the structuring of the learning experiences (i.e. telecoaching) is a complex process that comprises almost all levels and aspects of the educational practice. In order to evaluate this telecoaching process in a systematic manner I have chosen for the transformational perspective on education. In this chapter this analytical perspective will be used to specify (a) a general evaluation approach for telelearning processes, and particularly (b) a method for evaluating the telecoaching which has been practised in the TAET-course. I will start with the construction of a more general analytical framework that can be used to evaluate the entire process of telelearning.

In educational research of online courses we can differentiate seven analytical levels which have to be taken into account. Each level has its own peculiarities, potentials and problems. In the absence of a funny acronym, I will call it the SLNM: Seven_Levels_ No_More. In the next table these seven levels of telelearning are presented in a scheme in which the main features of the levels and the corresponding potential problems are outlined.

|

Aspects

|

Features

|

Possible Problems

|

|

Evaluation

|

Intricate system of evaluation instruments and procedures

|

No/inadequate evaluation tools; unsystematic use of evaluation tools

|

|

Coaching

|

Intensity and temporality of individual and collective return-information

|

Lack of or inadequate feedback: too little, too late

|

|

Community

|

Lively learning community that motivates individuals and stimulates them to cooperate in collaborative learning

|

Failing community building: boring, irregular contact, etc.

|

|

Assignment

|

Structuring and content of assignments

|

Badly composed series of assignments

Ambiguous, insufficiently demarcated assignments Structured & non-structured assignments |

|

Course Content

|

Quality & transparency of course information

|

Poorly specified course content; unclear level of expectations, etc.

|

|

Basic Skills

|

Basic computer, network & internet abilities of students

|

No or not enough computer, network and/or web literacy

|

|

lnfrastructure

|

Access to network and to personal computer

|

No access, slow access, disturbed access to network

No access to computer or access to 'underachieving' computer |

This SLNM-model can be used for (a) the construction of a theoretical framework and literature study, (b) the development of a questionnaire for TAET students and teachers, and (c) the empirical analysis of TAET course. In this thesis I concentrate primarily on the community and the coaching level. Since coaching is also inextricably bound up with course content and assignments, these levels will also be discussed. Other levels will only be touched on briefly, either due to time constraints or due to a lack of direct connection with the subject of this thesis: What does coaching 'look like' in a virtual learning environment and how can coaches stimulate the development of a vital learning community.

My hypothesis will be that the effectiveness of telecoaching depends primarily - though not exclusively - on the extent in which coaches succeed in moderating collaborative learning processes between and among students (and instructors). I presuppose that the creation of a learning community during a course is one of the most critical success factors of tele-education.

My empirical investigation will be directed by this main question:

-

what activities and roles of coaches have an impact on the learning process

as well as on the development of a learning community?

This question can be subdivided into these subquestions:

- What are the activities of coaches that stimulate and moderate self reflective learning practices?

- To which extent and in which forms has a learning community been developed in the course?

Below I will indicate what aspects of the different levels I believe are important and can be analysed and what I will leave out due to time constraints (pragmatic reason). For some levels I have worked out some indicators to be measured. Some of the questions that were asked in the questionnaire are inserted behind these indicators.

Infrastructural Level

The infrastructural level is defined by the conditions that facilitate good (fast, reliable etc.) access to personal computer, local networks, and the internet. The infrastructural level doesn't really concern the main theme of my thesis. Yet, some TAET students didn't possess a PC when they started the course and were enabled by the faculty to borrow one. And as we will see in the next chapter, some students had problems getting a reliable connection with the TAET-site.

In the questions on infrastructural level respondents were asked to briefly state the problems they had with the technology (network, computer) and also indicate positive experiences. This was specified in the following questions:

- Did you have problems with the technology (computer & network)?

- Did you have problems with your personal computer?

- No computer, Computer too slow: underachieving PC

- Inadequate Software

- Did you have problems to get access to the Twente network?

- Did you have problems with your own internet connection?

- How did it influence your work rhythm?

Basic Skill Level

The basic skill level is defined by the specific state of the basic computer, network, and internet abilities of students. In the studies I've read so far a recurring problem is pointed out: the lack of basic computer skills and webwisdom, combined with unfamiliarity with the electronic learning environment. Some studies report students' frustrations due to technological problems and suggest an introductory course before they really get started. In such introductory courses students can acquire basic computer skills, learn how to surf on and search the web, and get familiar with the electronic learning environment. We know in advance that quite a few TAET students had problems originating in a lack of computer- or webwisdom, especially with building a website in one of the first courses. They also had to become familiar with the electronic learning environment.

The questions on basic skills can be specified as follows:

- What was your basic skills level like when you started?

- related to computer skills

- related to internet skills

- related to electronic learning environments

- How long did it take you to get familiar with TeleTOP?

Course Content Level

The course content level is defined by the quality and transparency of the material that is used in an online course. Course content relates to:

- Quality and level of difficulty of the study material.

- Structuring of the whole course (order of subjects).

- Relationship between study material and new subject.

- Logical coherence between subjects.

On all these four items students will be asked some questions.

Assignment Level

The assignment level is defined by the structuring and content of assignments. The assignment level can be questioned and analysed as to:

- investment of time

- connection of assignments per subject

- clarity of assignments

- scope of assignments: too broad, too narrow (restricting creativity)

- relevance of assignments, etc.

It will not be easy to answer questions for this level for TAET students, because there were generally many assignments per subject and memory may have faded.

Community Level

The community level is defined by the imagined and experienced community that motivates students and stimulates them to engage in collaborative learning. The danger inherent in distance learning is that the social aspects of learning are getting lost. Social embedding of a learning process is of paramount importance, not only for an efficient learning process, but also for future professional practices in which collaboration is of vital importance. In some studies students' wishes to be part of a learning community is explicitly reported (transformation from outsider to insider) .

Cooperation can be measured for example as to

- Broadness of participation

- Intensity of participation

Sources of information for TAET-students are

- Discussion page

- Q & A page

- Workspace

- Groupmail

- Personal email between students (this can only be measured by asking the students if and how much email contact they had with fellow students).

Coaching Level

The coaching level is defined by the intensity and temporality of individual and collective return-information. Coaching refers to coaching activities of the instructor. In general we can say that coaching has two basic components: (a) instruction and (b) process control. These components will be subdivided later (e.g. different roles of the teacher: instructor, judge, motivator, provider of examples, advanced organiser, etc.). The instructor is the person to develop and control the quality of the (collaborative) learning environment and learning process and the one who can moderate the social embedding of the learning process.

In the teachers' questionnaire questions concerning available time for coaching and views on coaching will be included (for example: "what has been - or should be - your role in stimulating a collaborative learning process?") . In the students' questionnaire explicit questions about expectations and appreciation will be included.

Evaluation Level

The evaluation level is defined by the intricate system of evaluation instruments and procedures. In my empirical investigation I will not enter into the discussion about course evaluation. My investigation is itself a form of evaluation research.

Yet I will complete my TAET research with conversations with some experts of the Open University [Heerlen] on the issue of coaching strategies and practices. My hypothesis will be that the introduction of tele-education generates an increasing coaching need of students/trainees. A kind of 'revolution of rising coaching expectations'. Telelearners who present a paper or assignment expect an adequate, personal and above all fast reaction. My question to the experts will be how they practically handle this increasing demand of adequate, personal and fast feedback. (a) What problems do they identify: where do things go wrong and why? (b) What are the strategies to solve these problems: how can you realise a good coaching that comes up to the coaching expectations of students in a situation of scarce means?

Research Method

In my qualitative research project I have drawn upon the following sources of insight and information:

- A webbased questionnaire for my fellow TAET-students (also for the students that dropped out).

- A webbased questionnaire for the TAET-teachers (core courses and optional courses).

- My own knowledge of the TAET course stemming from my participation as a student [see A personal view].

- Personal email messages from and to students and teachers (during the whole training).

- Workspaces on TeleTOP for the different courses.

- Question and Answer pages on TeleTOP for the different courses.

- Course instructions.

- A questionnaire for some experts in the field of coaching at the Open University (Heerlen)

- Personal communication with some university teachers who have had experience with coaching in online educational learning processes.

- Personal communication with three teachers whom I asked to read part of my thesis (results of the empirical part).

Questionnaires and Response

The urls of the questionnaires were sent to my fellow students and teachers in a letter sent by email, explaining the purpose of my research. In the weeks after I was so fortunate to receive quite a number of replies.