Peculiarities of Cyberspace

Virtual community | Not a second-hand world | Networks of the future | Quantity creates quality | Community | Face-to-face or CMC? | P2P: networks of unknown friends | Flash Mobs | Second Life | Online morality and decency

Hypertextual Revolution | The future of the semantic web

Communicating on internet | E-mail: use & abuse of electronic messages

Anthropology of the Internet A stateless society? | Simple questions

Internet Use(rs) Cybergeography | International | U.S.A. | Europe | Netherlands | Closing digital divides

Cyber Capitalism A land without scarcity | Liberty or Equality in Cyberspace | Internet Shake-out? | Search Engines | Providers | A new colonial war?

Learning at Distance Educational revolution | Learning in your own time | Learning & teaching styles | Net-Students learn better | Learning without frontiers | Telecoaching

NetLove & Cybersex Intimate at a distance | Bodiless intimacy | Eroticizing virtual reality | Virtual & local relations | Netlove | Pornography in Cyberspace | Child Pornography | Regulation of Cyberporno | CyberStalking

Politics Egypt: Facebook Revolution?

Cyberterrorism Jihad in the Netherlands | Jihadists running Wild(ers)

Death & Mourning Immortal in the web | Virtual graveyard | Virtual mourning groups

With its chat rooms, online discussion groups, blogs, profile pages and web forums internet offers formerly unknown possibilities for communication and personal expression. Every new technology that passes by also brings along the shadow of criminality and indecency that follows. We are living in an era in which anybody can publish anything about all the others. It is hard to remain individually in control of your own reputation. On internet a trace of information fragments about us is saved, which are accessible to anyone via a Google query. The possibility of saying ‘anything’ under the protection of a pseudonym may lead to viral forms of public humiliation and the dissemination of malicious gossip. It leads to a permanent chronicle of our private lives (sometimes not very reliable and sometimes completely false). This chronicle pursues us wherever we go, and is accessible to friends, strangers, potential lovers, neighbours, relatives and so on. According to general consensus, decency on internet is in a sorry state of affairs. Internet seems to be an accumulation of gossip and backbiting, of rumours and slander. This has far-reaching consequences for the online clash between freedom of speech and privacy. According to the Amsterdam superintendant Bernard Welten the right of privacy has always been “the shelter of evil” [Bernard Welten - Superintendant Amsterdam].

A new kind of digital panopticon has come into being. This is a system no longer requiring a ‘Big Brother’ to watch over our shoulders, because we keep an eye on each other constantly anyhow. The internet creates an environment in which someone can become famous in the blink of an eye, only usually this fame is based on something the person in question would like to forget as soon as possible.

We need to protect our privacy to ensure that the freedom of internet does not make us less free. But we also have to find a balance between the protection of privacy and the freedom of speech. Common cultural norms should be developed to deal with private information on internet. And legal remedies should be established for people whose rights have been violated. But —as we could have learned from the past and as will be demonstrated for recent years below— the law is an insignificant instrument compared to social norms.

Identity and civilization

Social control and decency

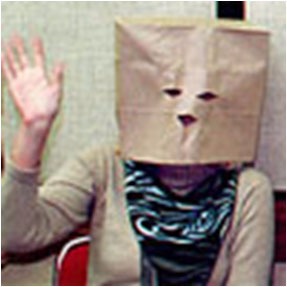

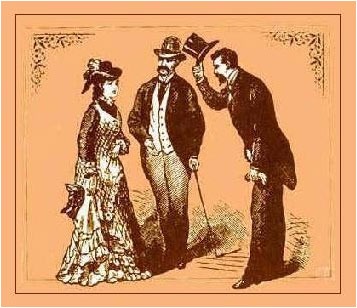

When participating in public life —at work, at school, in the neighbourhood, in politics or just in the streets— we participate as ourselves. We do not wear balaclavas (unless we camp on the North Pole), no masks (unless we celebrate carnival), and no clothes concealing our personal features (unless we are devoted orthodox muslim women). We show who we are. Even if people do not know exactly who we are, they can still recognise us by our external features at our next meeting. This authentic identity makes us approachable as far as our deeds are concerned: what we do and what we say can be connected to a specifically identifiable person by our fellow citizens. They can praise or criticise us for this, because they know who they are dealing with. This does not only create clarity (because we act openly), but also trust.

We operate in a public order in which irresponsible or antisocial behaviour can be identified, in which the individuals showing this behaviour can be called to account, and in which they can be disciplined, if necessary.

Undesired behaviour can be corrected in several ways: by a reproachful look, by a friendly request (‘please don’t stroke my buttocks anymore’), by public admonition (letting everyone know: ‘he is battering his children’), by conditioned threat (‘if you ..... once more, I will .....’), or by social exclusion. If all this does not work, and the violation of the social order is serious, we always have the possibility in democratic constitutional states to appeal to the even stronger arm of police and justice. We then report illegal or criminal behaviour. But in general deviation from social norms is suppressed by social sanctions. The social order is not only maintained by negative consequences to the violation of norms in force, but also by rewarding consequences to norm conformity. Opposed to negative sanctions (means of coercion), such as reticence in contact, contempt and antipathy, we find positive sanctions (inducements), such as attention, responsiveness, respect and sympathy. In varying combinations and sequences both means of coercion and inducements are used to prevent or redress violations of norms.

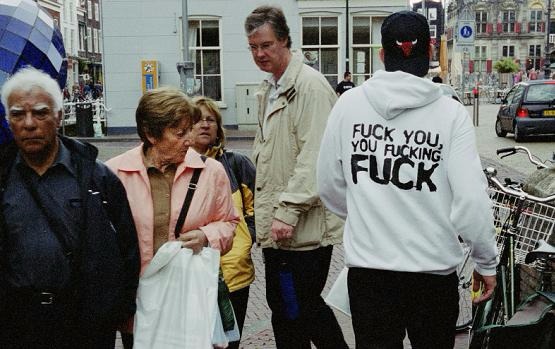

Obviously opinions differ on what ‘socially undesired’ behaviour is. What is ‘undesired’, ‘indecent’ or ‘rude’ to one person, can be quite ‘normal’ to another. This depends on our upbringing and the values and behavioural norms that we consider ours. But it particularly depends on the nationally and locally strongly varying cultures, and on the social, ethnic or religious background. While in some cultures it is ‘decent’ to cover your whole body, in other countries both sexes walk around almost naked. Besides, the social conventions differ according to specific situations: clothing that is correct on the beach, is indecent in town or at a funeral. Therefore undesired behaviour is behaviour that deviates from our subjective and situationally varying norms and values.

|

Norms and values

‘Values’ are universal moral standards allowing us to judge human behaviour: justice, freedom, charity, honesty, and so on. These starting points are the basis of the definition of specific agreements about certain behaviour in specific situations. Norms are mutual behavioural expectations charged with values. Or, in classic sociological terms: “The normative complexes that are concentrated around certain values stabilise the processes of interaction and communication; the goals direct the collective behaviours; together the expectations form a pattern, offering fixed frames of references to the interacting persons” [Van Doorn/ Lammers, Moderne Sociologie1976:270].

Reproduction by socialisation Guarantee by social control: Norms and values are reproduced from generation to generation by upbringing, socialisation and ‘the strength of the example’ (role models) and are guaranteed by social control. Social control sees to it that a certain balanced situation in the community is maintained or regained, which is of vital importance to its stability. A community unable to deal with internal and external balance disturbances will not survive long. This also goes for online communities and networks, and perhaps even to a greater extent.

|

Some norms and values are considered to be so vital that we have established them in laws: our fundamental norms and values have been objectified and codified in laws that are safeguarded by the government:

- citizens cannot use violence towards each other: no killing, battering or raping (protection of integrity of the body).

- citizens cannot appropriate the properties of other citizens: no theft, fraud or swindle.

- citizens cannot violate the privacy of other citizens: I am the only one to determine who enters my house through the front door.

- citizens cannot insult or slander each other in public: no ‘gossiping’ in public.

We find them so important that we have established special bodies to maintain these objectified norms and values: the police see to it that the laws are complied with, and the judiciary punishes those who break the laws. Citizens violating the objectified norms of good behaviour are called to account and are punished by the government. In order to do this, the government needs to know ‘who’ has violated which law in which way. As long as the identity of the murderer, thief or rapist is not known yet, the government cannot arrest this person, nor bring him or her to court. In principle the government ‘knows’ all citizens. Each citizen has a passport (identity card) and the government knows where we live. If this is not the case it will be difficult: perpetrators often operate with fake identity cards or back out of the Dutch jurisdiction.

Social conventions and manners

Apart from the norms and values established in laws and official regulations, there are numerous other social conventions and manners that are of the utmost importance to the social cohesion in society and also to the safe and pleasant livability. They are elementary preconditions for a peaceful and livable society.

The way you hear is, ...

|

Social conventions and civilising norms: we all know them. I make no claim to be exhaustive in the following list:

- It is indecent not to greet each other when we meet (hello, shake hands, kiss).

- Approach each other with respect.

- Thank someone when someone does you a favour.

- Apologise when you accidentally stepped on someone’s toes.

- Do not resent someone’s space in the public domain.

- Respect the privacy of other citizens.

- Do not speak ill of someone behind his or her back.

- Give an honest answer when you are asked a question.

- Do not throw your rubbish in your neighbour’s garden.

All these acts are not done, because they humiliate fellow citizens [Margalit 1996]. In a civilised society we say: ‘you don’t do this’. These norms of decency cannot or only to a very small extent be enforced or guaranteed by the government. They must be applied and maintained by the citizens themselves. A government can propagate these norms, but not prescribe them. You do not have to shake hands with or kiss each other while greeting, you cannot be punished for not apologising for stepping on someone’s toes or accidentally bump into someone; you are not put in prison when you shout ‘filthy whore’ to a woman in the street, and no police will come at your door when you did not get up for an elderly or disabled fellow citizen in the train. It is up to society itself, that is up to us, civilised citizens, to adhere to these norms of decency and to see to it that other fellow citizens do the same thing. It is not as easy at that.

We all know the examples. Who has enough courage to say something when a muscular bully barks at his wife and children? When a child is bullied at school by a ‘tough’ guy, which fellow student protects the victim? Who says something when someone is disrespectful about someone else? Who takes action when someone jumps the queue at the checkout of a supermarket? If someone indifferently passes someone who has fallen down on the street, what do you say? If someone calls a group of homosexuals ‘filthy faggots’, who calls something back? If someone runs down other people in public spaces, who shouts ‘mind your detention during Her Majesty’s pleasure’?

In all these cases it often is difficult for individual citizens to undertake something – even if they perfectly sense that something is happening they strongly disapprove of and even if they feel morally obliged to act against this indecent behaviour. But still they do not do it, because they fear the consequences. You are at risk when you call the indecent (‘the scum’, ‘the loud mouths’, ‘the anti-socials’) to order. Also in this respect —and often rightly so— we are calculating citizens balancing risks against each other. But that is also why we have such great respect for Joes Kloppenburg († 1996), Mijndert Tjoelker († 1997) and René Steegmans († 2002), who did act against assholes, but who paid for it with their lives.

We cannot delegate pushing back the ‘culture of the loud mouths’ to the government. Citizens themselves have to resist indecency, civil aggression and ‘meaningless violence’. This requires self regulation and self organisation from society.

|

Imposed absolute norms from above

Formerly norms valid for behaviour and binding in the solution of conflicts were not considered to be human products. Rather, their legitimacy was based on the absolute sanctity of commandments (such as the ten commandments Moses received from God on Mount Sinai). Those who deviated from it would be punished by devilish magical effects, by restlessness of the spirits, or by the revenge of the gods. These norms were constant and omnipresent. They had to be learned and interpreted correctly, in compliance with the reigning religion, but they could not be created. Interpreting the norms was the exclusive task of those who were most familiar with them: the village senior or the oldest of a kinship group, and very often the magicians and priests. As a consequence of their specialised knowledge of the magical powers they knew how to interact with supernatural powers. Yet, also new norms came up, imposed from above by a new charismatic revelation [Weber, Economy & Society, p. 760]. So, a norm does not always have a rational justification or origin. In the course of time some norms lose their original context because society changes.

|

Decency is complying with unwritten yet empirically valid norms and values. The validity of a norm becomes apparent in its current influence on our actual deeds. By sticking to norms of decency our social actions become predictable. When, in our daily lives, we take dominant social conventions into account, we act in a decent way.

To many people ‘decency’ has acquired a negative undertone, because it is compared with narrow-mindedness, pettiness, conceit and lack of tolerance for other behaviour. With an appeal to decency, for example, the discrimination of homosexuals had been maintained for years. The mistrust of norms of decency is mainly a result of experiences with authoritarian formalities (intended to enforce respect for non-democratically legitimised authority), and with restrictive norms of morality and chastity (no sex before or outside of marriage and of course the heterosexual norm).

This mistrust has turned into aversion with some people. “The concept of decency is so multi interpretable and has so often been deployed as a political weapon that I have taken a strong aversion to it. So I will not be guided by it” [Marcel Vreemans in Het Vrije Volk - 1.6.2008]. When the Dutch Prime Minister Balkenende tried to breathe new life into the concept of decency (on the pretext of: Decency should be practised) most critics immediately smelled an irritating musty smell — the smell sticking to every attempt to restore old norms and values. The mistrust of conservative or restoring pleas for decency is understandable — they usually lead to a restriction of our liberties. The ‘moral censors’ and ‘moralists’ nostalgically longing for the good old days are history.

There is another reason why decency has acquired such a negative undertone. Decency is often compared to enforcing accepted behaviour from above. However, this is not necessary. Under certain conditions common behavioural norms can also be established in a deliberating-democratic way. The social norms regulating our behaviour are usually based on consensus to a certain extent and are reproduced via social sanctions.

Nevertheless, decent manners are indispensible to a civilised society. Manners are formalised forms of self-control. And especially this self-control often seems to be lacking on internet.

Anonymity as shield and weapon

Freedom and disinhibition

When we participate in public life in cyberspace the case is even more complicated at first sight. On internet we usually operate anonymously or under a pseudonym. This anonymity is a blessing and a curse, a shield and a weapon at the same time.

a. Freedom of speech

|

PseudonymPseudonymity on internet does not mean being without an identity. With a pseudonym you are still a person, with an identity and a past recorded in a database, with an IP-number and an e-mail address. So you can be retrieved, but not for anybody. Only the website owner or forum manager can, if necessary, find out who you really are. They are also capable of excluding troublemakers by blocking their IP-number. However, you remain anonymous to the ordinary members of virtual communities.

|

On internet everyone can shout as loudly as desired. Thanks to the internet everyone is able to express her or his opinion plainly at present. Outside the internet this was and still is completely different. They who want to air their opinion via the ‘old’ media, are stopped by gatekeepers who select what will and will not be published. Based on their own journalistic norms newspapers, magazines and publishers decide if and how they publish something. Radio and television editors themselves determine who can talk about which issues. On internet these filters can be skirted. The constitutional right of freedom of the press was always restricted to those who possessed a press (or a radio or television station, or communication satellites). On internet everyone not only has a press of one’s own, but also a radio and television station of one’s own. Internet has brought the constitutional right to freedom of the press within anyone’s reach. Anyone can make use of weblogs, discussion forums, instant messaging and database on internet, to express their opinions and judgements, analyses and illusions, frustrations and hope, experiences and fantasies.

In the virtual world one can move more freely than in local society. The main reason for this is that on internet one can operate mostly anonymously or under a pseudonym. On internet it is possible to operate under a pseudonym (a pseudo identity) without giving up one’s true identity. Only in very specific circumstances the government can force providers or administrators of web forums to reveal the identity of a user. Eventually nearly all utterances or actions of internet users can be traced. Yet, internet allows for a feeling of unknown freedom.

People are reticent to say what they really think when they stand face-to-face in front of an authority. They fear disapproval and punishment. However, online people are more inclined to express themselves in no uncertain terms or to misbehave. They imagine they are invisible and are tempted to do things they normally are afraid to do, or are not allowed to do. The anonymous nature of internet communication gives the participants a great feeling of freedom. Due to this disinhibition people are inclined to express themselves more directly, emotionally and disinhibitedly about the most intimate and ultimate subjects. Anonymity enables people to hide behind their computers and to say anything they have on their minds, without fear of immediate repercussions for the local social lives. Consequently virtual communities normally display a much more disinhibited —if not rougher— communication culture than in local face-to-face communication.

|

Anonymous communication as a right?

Historically anonymous communication has always been at stake in the power struggle between governments that wanted to restrict the dissemination of political and religious ideas and authors who were unconcerned about the ban on anonymity. The essential question at issue to this day is: does the right to publish anonymously result from freedom of speech?

The founders of the American constitution embraced anonymous communication in the political domain as a way of putting forward unpopular, contrary opinions without experiencing personal drawbacks. The founders themselves also made use of this. The essays in the Federalist Papers were published under the pseudonym ‘Publius’ [Zittran 2008:316, note 67]. They opposed the attempts to force anonymous authors to reveal their identity. Their main argument was that forced revelation damages the freedom of press. But in the Netherlands anonymity is no such constitutional right as the right to privacy. In 1525 Charles V banned the books of Martin Luther and his followers and all books without title and sender. In case of violation, without showing remorse, men had to be put to death by the sword, and women were buried alive. This strict prohibition had little effect though. Luther kept publishing nearly all his treatises anonymously. In 1559 this was followed by the papal ban on all anonymous publications written by heretics. From the end of the 18th century on the French occupier continued the prohibition of anonymous publications. In 1789 this is laid down in law: “Every citizen can express and distribute his feelings, in such a way as he pleases; if not contrary to the purpose of society. The freedom of press is sacred; if and only if the writings are provided with the name of the publisher, printer or author [Article 16 of the Civil and Political Basic Principles]. Not until 1886, through intercession of professor Simons from Leyden, did anonymous publishing become a right. According to him freedom of expression could only be optimal if there is no obligation to signing. The right to anonymous publication was only nullified by the German occupier during World War II, as was also done earlier by the Spanish and French occupier [Ekker 2008].

Those who are invisible cannot be called to account for the consequences of their own behaviour. In book 2 of Politeia the classical Greek philosopher Plato tells the story of the magic ring of Gyges. This ring offers the owner the power to become invisible at any desired moment. To Plato this is the best way to establish if someone is morally good: when you do not have to be afraid of the consequences of your own actions and yet act morally responsible. The moral of Plato’s story is that nobody is so virtuous to resist the temptation to steal, thanks to the power of the ring to make someone invisible. In other words: morality is a social construction. The source of it is the desire to maintain one’s own reputation of virtuousness and honesty. However, when the social and legal sanctions that keep up virtuousness are not effective anymore (because one is invisible, anonymous), the moral character evaporates. Wie onzichtbaar is kan niet worden aangesproken op de gevolgen van zijn eigen gedrag. In boek 2 van Politeiavertelt de klassieke Griekse filosoof Plato het verhaal over de magische ring van Gyges. Deze ring biedt de eigenaar de macht om op elk gewenst moment onzichtbaar te worden. Voor Plato is het de beste manier om vast te stellen of iemand in moreel opzicht goed is: als je niet bang hoeft te zijn voor de consequenties van je eigen handelen en toch moreel verantwoord handelt. De moraal van het verhaal van Plato is dat niemand zo deugdzaam is dat hij de verleiding kan weerstaan om te kunnen stelen dankzij de onzichtbaarmakende kracht van de ring. Met andere woorden: moraliteit is een sociale constructie. De bron daarvan is het verlangen om de eigen reputatie van deugdzaamheid en eerlijkheid te handhaven. Wanneer de sociale en juridische sancties die de deugdzaamheid in stand houden niet meer effectief werkzaam zijn (omdat men onzichtbaar, anoniem is), verdampt echter het morele karakter. Those who are invisible cannot be called to account for the consequences of their own behaviour. In book 2 of Politeia the classical Greek philosopher Plato tells the story of the magic ring of Gyges. This ring offers the owner the power to become invisible at any desired moment. To Plato this is the best way to establish if someone is morally good: when you do not have to be afraid of the consequences of your own actions and yet act morally responsible. The moral of Plato’s story is that nobody is so virtuous to resist the temptation to steal, thanks to the power of the ring to make someone invisible. In other words: morality is a social construction. The source of it is the desire to maintain one’s own reputation of virtuousness and honesty. However, when the social and legal sanctions that keep up virtuousness are not effective anymore (because one is invisible, anonymous), the moral character evaporates. Wie onzichtbaar is kan niet worden aangesproken op de gevolgen van zijn eigen gedrag. In boek 2 van Politeiavertelt de klassieke Griekse filosoof Plato het verhaal over de magische ring van Gyges. Deze ring biedt de eigenaar de macht om op elk gewenst moment onzichtbaar te worden. Voor Plato is het de beste manier om vast te stellen of iemand in moreel opzicht goed is: als je niet bang hoeft te zijn voor de consequenties van je eigen handelen en toch moreel verantwoord handelt. De moraal van het verhaal van Plato is dat niemand zo deugdzaam is dat hij de verleiding kan weerstaan om te kunnen stelen dankzij de onzichtbaarmakende kracht van de ring. Met andere woorden: moraliteit is een sociale constructie. De bron daarvan is het verlangen om de eigen reputatie van deugdzaamheid en eerlijkheid te handhaven. Wanneer de sociale en juridische sancties die de deugdzaamheid in stand houden niet meer effectief werkzaam zijn (omdat men onzichtbaar, anoniem is), verdampt echter het morele karakter.

According to Plato this is convincing evidence “that one is not righteous of one’s own free will, but only if it is the only thing to do.” The same theme returns in The invisible man by H.G. Wells [1887]. This science fiction novel is a critical demonstration of the human inclination to become immoral as soon as one is in power. Due to his invisibility he acquires an enormous power: he can steal, kill and abuse anybody without fear of being caught. Voor Plato is dit een overtuigend bewijs “dat men niet uit vrije wil rechtvaardig is, maar slechts als het niet anders kan.” Hetzelfde thema keert terug in The invisible manvan H.G. Wells uit 1887. Deze sciencefictionroman is een kritische demonstratie van de menselijke neiging om immoreel te worden zodra men macht verwerft. Door zijn onzichtbaarheid verwerft hij enorme macht: hij kan stelen, doden en iedereen misbruiken zonder angst om gepakt te worden. According to Plato this is convincing evidence “that one is not righteous of one’s own free will, but only if it is the only thing to do.” The same theme returns in The invisible man by H.G. Wells [1887]. This science fiction novel is a critical demonstration of the human inclination to become immoral as soon as one is in power. Due to his invisibility he acquires an enormous power: he can steal, kill and abuse anybody without fear of being caught. Voor Plato is dit een overtuigend bewijs “dat men niet uit vrije wil rechtvaardig is, maar slechts als het niet anders kan.” Hetzelfde thema keert terug in The invisible manvan H.G. Wells uit 1887. Deze sciencefictionroman is een kritische demonstratie van de menselijke neiging om immoreel te worden zodra men macht verwerft. Door zijn onzichtbaarheid verwerft hij enorme macht: hij kan stelen, doden en iedereen misbruiken zonder angst om gepakt te worden.

|

b. Identifying online criminals and miscreants

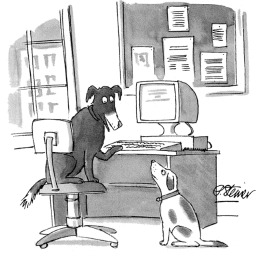

“On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog”

Peter Steiner, in: The New Yorker, 6 juli 1993

|

Anonymity allows us to discuss more freely and disinhibitedly about embarrassing or stigmatising subjects, but can also be a community’s biggest enemy. The anonymity of online communication is a blessing for those who attempt to deregulate the network itself and its operating virtual communities. It does not only offer a mask to online frauds and thieves, but also to hate mongers, preachers of violence, violators of reputations, child pornographers, paedophiles and terrorists. The most diverse types of criminals have settled on the internet to enrich themselves illegally. Extremist political factions use internet to disseminate their discriminating and hatred-sowing propaganda. But this analysis is not about cybercrime, but about virtual indecency, public humiliation and vicious gossip, which is —as we will show at great length later on— in itself a very complex problem to begin with.

Indecency on internet cannot be curbed by legal measures or criminal sanctions. They who become the victims of malignant, reputation-destructing gossip on internet often do not know who is responsible and have, on the face of it, few means at hand to effectively defend themselves on internet.

NetSluts and NetBastards

Internet is a place where we can articulate our own identity, and at the same time a place where we can operate anonymously. After all, anonymity means hiding one’s identity. In cyberspace people say and do things they would normally not say or do in the local world. We have seen that people feel less inhibited and express themselves more openly, because they can operate anonymously or under a pseudonym. This anonymous conversation is the result of (a) idle mechanisms of local social control and (b) a low risk of legal prosecution. As long as nobody knows your name is ‘Cinderella’, you need not fear that you are personally confronted with the consequences of your online behaviour.

The civilisation of a society primarily reproduces itself by the operation of customs, morals, solidarities and common interests. So a society stabilises more or less unconsciously, as a non-desired and unintended side effect of our traditional, affective and utilitarian orientations and actions [Bader/Benschop 1988:265 ff]. Social control and legislation are the two basic mechanisms warranting the preservation of this society, and under certain circumstances its transformation as well. The elimination of these two guarantee mechanisms seems to lead to a premium on extreme forms of social actions. The disinhibition ensuing from anonymous communication is therefore a two-edged sword.

On the one hand we see that people share very personal and intimate stories about themselves. They reveal secret emotions, fears and desires. Or they show exceptionally friendly and generous behaviour. But apart from this amiable, good-natured disinhibition there is also a vicious disinhibition, expressing itself in profusely gross language, rude criticism, fear, blind hatred and even in threats. It is a raging catharsis in which the most revolting desires are indulged.

As soon as the mechanisms of social and legal control have been suspended — or at least pushed into the background — a premium is put on excessive and obtrusive flirting (netslutting) on the one hand, and on grossly provoking and insulting (netshitting) on the other. Netslutting is harassing people (mainly women) with unwanted attention, with propositions for undesired sexual intimacies and sometimes with credible threats too. You can also call it a form of online stalking, cyberstalking [in Cyberstalking this phenomenon is analysed extensively]. Netshitting is the dissemination of blunt criticism, gross insults and often also threats. When enough netshits gather in certain internet locations, they can orchestrate digital hanging parties (‘flame wars’), in which the victims are persecuted by a raging mob. This does not only take place by organising a witch hunt on internet. Frequently the dividing lines between the virtual and the local are broken and the victims are also threatened in their private lives, in the streets or at work. A number of examples are discussed below.

Culture of the loud mouths: crying for attention

|

Exponential reinforcement of the extreme“Everywhere there is a growing number of confrontations, and they become harder, in real life and also on internet. Multiply this with the growth of the number of people on internet, and the time they spend there, and with the safe distance from which opinions can be expressed. This will lead to a considerable reinforcement of the power of the extreme of online expressions” [Johan Heslinga, Fok].

|

The combination of netslutting and netshitting results in a venomous mixture that can best be described as the culture of the loud mouths. This is a culture with a specific group dynamic of its own, and in which the participants try to outdo each other in unvarnished, unseemly big and strong talk. As a result of its detachment and anonymity, internet is a unique vehicle for unleashing hidden rage. Virtual communication is a disinhibited form of communication and is much rougher in the expression of dissatisfaction and aggression. In particular shocklogs or provoking blogs (with GeenStijl as no.1 in the Netherlands) offer a platform for this phenomenon. They express a more or less strongly organised popular rage against anything that is left-wing or multicultural. In the web forums of Geen Stijl, Elsevier and the Telegraaf the abdomen of the Dutch civilisation rules.

|

Unchained rage

Behind the unchained rage in cyberspace lies resentment: the deep-rooted, and thus not indulged feelings of revenge of the powerless towards the powerful.

“All sick, dirty hate fantasies devised during many nights of drunken excitement was exposed in full rage in full daylight” [Stefan Zweig]. There used to be the ‘silent majority’, but thanks to the internet a platform was found for this silent majority. “This silence has come to an end once and for all. Now we discover that a new, prosperous lumpenproletariat has risen, a crowd that feels permanently and to the soul misunderstood and cheated, and expresses this as loudly as possible. The digital culture has given this crowd a voice” [H.J.A. Hofland, NRC, 7.12.2008]. |

In local live people are forced to show consideration for others and to meet the ‘normal’ expectations. Internet forums are sanctuaries with little social control. Participants who voice extreme opinions ask for attention. If they do not get it, they are tempted to express themselves in an even more extreme way. Forums unable to regulate themselves run the risk of being undermined. They go down in an uncontrollable jumble of bombastic, resentful muscular language. The risks grow even more when the boundary between virtual and local expressions fades.

The participants of anonymous conversations predominantly use informal language: street and pub language. As soon as this language is used and recorded in the publicity of cyberspace, its significance changes drastically. The difference is not only that in internet conversations the digital signals spread much faster over large groups of people, but also that they stick much longer. When, in a neighbourhood pub, someone indicates that he does not agree with the previous speaker by saying ‘drop dead’, this is only heard by the people standing close to the speaker. The utterance fades away as soon as the air vibrations transporting this message through the air die out. In the seclusion of the neighbourhood pub such an utterance usually means no more than that the speaker doubts the words of the previous speaker; in the full publicity of the internet such an expression quickly acts as a threat.

The participants of anonymous conversations predominantly use informal language: street and pub language. As soon as this language is used and recorded in the publicity of cyberspace, its significance changes drastically. The difference is not only that in internet conversations the digital signals spread much faster over large groups of people, but also that they stick much longer. When, in a neighbourhood pub, someone indicates that he does not agree with the previous speaker by saying ‘drop dead’, this is only heard by the people standing close to the speaker. The utterance fades away as soon as the air vibrations transporting this message through the air die out. In the seclusion of the neighbourhood pub such an utterance usually means no more than that the speaker doubts the words of the previous speaker; in the full publicity of the internet such an expression quickly acts as a threat.

Agression on internet

It is often said that it is not that bad with indecency and threats on the internet. After all only virtual events are involved that do not really affect us. In this view internet is seen as an outlet for feelings of hatred and suppressed aggression. Behind it lies a well-known common-or-garden theory of aggression. In this theory aggression is seen as an amount of energy confined in a pressure-cooker. In order not to let the ‘barrel full of aggression’ explode, the valve has to be opened once in a while. This allows the persons involved to express violent feelings of hatred and revenge and decreases the boiler pressure.

But this presents a distorted and simplified picture of how aggression operates. People who regularly express themselves aggressively are more inclined to show violent aggressive behaviour. And therefore aggressive behaviour is usually preceded by verbal aggression. People who are in a state of great uncertainty and emotional excitement are more easily inclined to tumble over each other in bold utterances and extreme proposals. Sentiments that arise on internet can quickly transfer to the local world. It is impossible to physically abuse or to kill people on internet. But it is possible that such a threatening atmosphere comes up that the boundary between the virtual and the local vaporises, and the threat moves on to the private and work domain of the victim.

Shift in private and public domain

With the help of cheap sensors (mobile phones with camera) and networks citizens can distribute something they have recorded on their pavement or in a restaurant extremely fast all over the world. Nearly all our activities can be broadcast. Search YouTube for ‘angry teacher’ and you will find hundreds of videos of teachers hitting the roof. People’s lives can be ruined in a split second, even if the reason is just a lapse or small mistake.

- “Thanks to internet you need not be a famous Dutch person anymore to become the talk of the town. Gossip magazines used to have the exclusive rights on this, but now anyone can write anything about anyone else. With a few combinations on the keyboard you can make anything known on the web, be it a lie or the truth” [Van Wijk 2007].

At present almost everybody is able to register your good and bad deeds in sound and picture. Before you know you are an involuntary well-known Dutch person, or even an involuntary YouTube celebrity (‘welebrity’). If someone wants to prevent this from happening he or she is wise not only to check if Heleen van Royen (a Dutch author with a reputation for gossip) is near. It becomes increasingly difficult to prevent private conversations in the public domain —for example in a restaurant— from becoming public. The once so apparently clear borderline between private and public domain seems to blur. This is only facilitated by modern registration technologies, but is above all the result of people using these technologies in an irresponsible and indecent way.

|

Friendlier with friends

There is a striking difference between the internet locations where people operate under their own name and under pseudonym. On profile sites such as Hyves and Orkut, for example, the atmosphere is generally a lot better than on web forums allowing people to react anonymously. The reason is very simple: everyone publishes and reacts under their own name. People would not even think of irresponsible or rude behaviour there. Who goes beyond the limit is removed from the group of friends (in publicly accessible blogs where also non-friends are allowed, dissidents can be blocked by the user). “Reliability and quality are not enforced by lofty codes, but are realised by perfectly simple social control” [Stronks 2007b].

|

So specific use of the modern registration technologies can contribute to the blurring of the borderlines between the private and public domain. But also the values underlying the protection of our privacy have shifted in the course of time. In particular youngsters are keen on sharing personal information online via profile sites and friends-of-friends sites such as MySpace, Facebook, Orkut or Hyves. They share their everyday and special learning experiences and discuss them extremely openly. Many elderly and educators react rather paternalistically: children do not (yet) possess the judgement to know what they can and cannot share and therefore have an irresponsibly liberal or even narcistic way of dealing with their personal information. From this point of view young people should be protected against fast decisions which may lead to the loss of their privacy.

Closer research, however, shows that something else is going on. Most (also young) people take rather rational decisions about sharing their personal information. But they underestimate what may happen when this information is massively indexed, re-used, and used by strangers for other goals.

Most young people now growing up with the internet accept that they can give a public dimension to their personal life online. They even find it attractive to present themselves in the enormous publicity of cyberspace. “Who are you when you are still not present on internet?” Internet is a place where youngsters can show their identity (they have moved their threshold of shame and embarrassment out of the way). The great charm of profile and friends-of-friends sites is not secrecy, but autonomy: you keep control of your own profile and only engage in relations with friends of your own choice [Zittran 2008:233].

In agrarian village communities the citizens knew a lot less privacy than in a modern urban community — and in small rural communities they still have less privacy than in a big city. The life of people in small communities or villages is an open book compared to the anonymous existence of people living in cities. The other side is that someone who lives in a village is better able to keep his secrets, because he has a better control over them. A villager lives in a society that is built on personal, face to face contacts. This makes it much easier to identify irresponsible or anti social behaviour and accelerates calling people to account for this behaviour.

In cyberspace we operate in a strongly impersonal information and communication system. Our fellow citizens are faceless users of information and we can often only recognise our discussion partners by their pseudonym or avatar. Online they are only formally approachable on their utterances and acts: in practice they are for a greater part immune to the sanctions someone would like to impose on them.

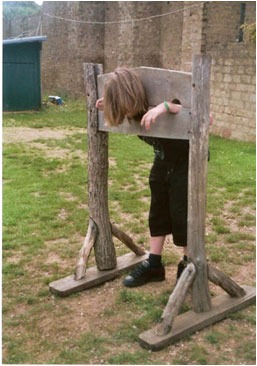

Virtualisation of the pillory

Pleasant and digital gossip

Gossip =blacken someone’s

reputation and launder onseself.

|

Everybody talks about other people. In itself there is nothing wrong with that. It is even healthy to talk about people in a group in which one participates – it creates a bond [Barkow 1995; Dunbar 1996; Baumeister e.o 2004; McAndrew 2008]. Gossiping is a completely different form of communication. Gossiping or backbiting is talking about someone in an unfavourable way when the person in question is not present. Therefore this person cannot defend himself against possible untruths or allegations. Gossip is passed from mouth to mouth and eventually assume a life of their own because people invent and add new things to this gossip. This way gossip can ruin reputations. The traditional or benign gossiping is usually restricted to a limited network of direct relations (circle of friends, colleagues, family, club) and usually stops before the boundary of the public domain. When the gossip enters the public domain, it transforms into defamation and slander (toxic gossip).

Defamation is blackening someone’s good name by accusing this person of facts he or she is guilty of. He or she who commits this, can be sentenced unless (i) the general interest requires that the facts are exposed, (ii) the action was undertaken as a necessary defence, (iii) or it could be assumed in good faith that these facts are true. The goal of defamation is ruining the victim’s reputation. Contrary to slander defamation is not about accusations of which one knows they are untrue. Often the accusations are exaggerated as much as possible to pillory someone as much as possible. Besides, the facts of which the victim is accused need not necessarily be punishable. Adultery or deviant sexual preferences are extremely suitable for defamation. Slander is blackening someone by publicly accusing him or her of facts that are generally known not to be true.

Homo Anonymus |

|---|

In case of the old gossiping people talk unfavourably about someone who is not present. In case of cyber gossiping people gossip about you while you are there. Unlike the old gossiping the gossip on internet is mainly disseminated online. The gossip is not whispered into your ear by someone you know, but is written down in the virtual publicity of cyberspace by an unknown person, hidden behind a pseudonym. The gossip in cyberspace spreads at supersonic speed and on the largest imaginable scale — world wide. Because the gossip is written down on internet, it stays there for years to come. In addition, it cannot or hardly be contradicted, even if the victim knows the nature of the circulating gossip. The only thing the old and the new gossiping have in common is their purpose: destroying the victim’s reputation.

We have seen before that defamation and slander are forms of “public gossiping.” Gossiping is permitted, although indecent, as long as you do not gossip publicly. This has far-reaching consequences. Who gossips in the public domain of the internet, is therefore virtually by definition guilty of defamation or slander. However, there are still few judges who have included this consequence in their judgements. Yet, the number of cases in which people are pilloried increases alarmingly.

Digital lynching

The classic pillory, used until the late middle ages, was a pole to which somebody was tied and exposed, as a punitive measure. According to the ruling laws sentenced criminals were literally exposed. The audience played an active role in it and was permitted to curse the punished person and throw rotten eggs or street rubbish at him or her. The goal of this punitive ritual was to brand the perpetrator as a criminal: he lost his face precisely because his face became known all over the town. A person guilty of serious crimes at the time, lost his ‘right to privacy’ (which evidently was not recognised as a right in the middle ages). Who was tied to the pillory by the court of justice might be so lucky that the audience did not agree with the sentence, which often led to a demonstration against those in power. When Daniel Defoe —author of Robinson Crusoe— was tied to the pillory in 1703 for writing a ‘subversive’ pamphlet (The Shortest Way with the Dissenters), the crowd covered the pillory with flowers and gave him an ovation when he arrived at Charing Cross (London). In the Netherlands the pillory remained popular well into the 18th century. Not until mid 19th century it was officially abolished as a punitive measure.

The classic pillory, used until the late middle ages, was a pole to which somebody was tied and exposed, as a punitive measure. According to the ruling laws sentenced criminals were literally exposed. The audience played an active role in it and was permitted to curse the punished person and throw rotten eggs or street rubbish at him or her. The goal of this punitive ritual was to brand the perpetrator as a criminal: he lost his face precisely because his face became known all over the town. A person guilty of serious crimes at the time, lost his ‘right to privacy’ (which evidently was not recognised as a right in the middle ages). Who was tied to the pillory by the court of justice might be so lucky that the audience did not agree with the sentence, which often led to a demonstration against those in power. When Daniel Defoe —author of Robinson Crusoe— was tied to the pillory in 1703 for writing a ‘subversive’ pamphlet (The Shortest Way with the Dissenters), the crowd covered the pillory with flowers and gave him an ovation when he arrived at Charing Cross (London). In the Netherlands the pillory remained popular well into the 18th century. Not until mid 19th century it was officially abolished as a punitive measure.

In case of digital lynching people are slandered via internet. Often, but not always, it is about personal settlements: accounts are settled between former lovers who divorce the hard way, between employees who feel treated badly by their (former) boss or employer, between students who fancy the same girl, or between neighbours who begrudge each other the light of day. Nationally well known persons —politicians, judges, actors, pop stars and other Well Known Dutch Persons— form the second category of potential victims. Insulting, slandering and even virtually threatening well known Dutch persons seems to have become a national sport on internet. By means of a digital lynching they are outlawed. In all these cases the goal is exactly the same again: damaging the reputation of either or not well known private persons or of the image of institutions or companies. In many cases revenge seems to be the chief motive. Public humiliation is the predominant goal.

|

|---|

Internet is used to settle outstanding personal accounts and to expose and redress exceeding of moral standards. These sanctions for improper behaviour are lifted to a new level by the internet: a permanent file of someone’s norm violation is established; internet users start behaving like cyber bloodhounds tracing norm violators (manhunt) and brand them with digital letters. The media and the legal system cannot and should not participate in the organisation of digital manhunts on individuals. The public nature of the internet has given birth to a new instrument for social control. This is the dark side of ‘empowerment’. As Howard Rheingold said, we used to worry about big brother, but now we should worry about our neighbours, our fellow passengers in the train, tram and underground, and arbitrary people living in our street. The online neighbourhood watch groups and vigilant committees are numerous.

Do you look around first nowadays when you pick your nose, or straighten your underwear? We are increasingly aware of possibly being watched. Apparently the authorities think they have a right to place surveying cameras anywhere, allowing them to improve safety. To what extent is people’s behaviour in public spaces influenced by the implicit potential of people in your neighbourhood who register your good and bad deeds? How do you prevent private conversations in public domains (as in a restaurant) from becoming public?

Worst cases

Bus Uncle - Hong Kong, 2006

Bus Uncle flies off the handle Bus Uncle flies off the handle |

|---|

On 27 April 2006 a young man with glasses taps a fellow passenger on the back, friendly requesting him to speak a little bit more softly in his mobile phone. The young man is Elvis Ho, 23 years old, real-estate agent. The man standing in front of him is Roger Chan, 51 years old, working in a restaurant and living with 6 cats. He turns around and reacts violently and threateningly. Chan, known as ‘Bus Uncle’ since the video has been published, starts ranting which lasts for about six minutes. His language use is extremely coarse. Hanging over the back of the seat with his fingers only a few inches away from Elvis’ nose, he screams: “I am under pressure. You are under pressure. Why are you provoking me?”

This scene is recorded by a third person who published it on internet afterwards. This video was published on YouTube by ‘beautyjeojihyun’ and was watched by 1.7 million people in the first three weeks of that month. Then several derived versions were made of it, such as a ring tone, a rap, a disco remix and a karaoke version. Via internet ‘Bus Uncle’ suddenly got the status of an online celebrity. Local reporters went after him, and pursued him – he became front page news.

Strikingly enough ‘Bus Uncle’ became very popular. He became a sort of hero who expressed the true feelings of ordinary people living closely together in a hectic city where you do not talk to strangers. Chan went berserk and many fellow citizens recognised that moment of failing aggression management. “I am Bus Uncle, potentially, and so are you. Each of us has a tiny, raging Bus Uncle buried deep within, just waiting to burst free. One tap on the shoulder is all it takes” [Eugine Robinson, Washinton Post].

Chan tried to cash in on his status of YouTube celebrity and has regularly been spotted with charming young women in nightclubs since then. A few weeks after the video appeared on internet, Chan was beaten up during a targeted attack on the restaurant where he worked. In Hong Kong the video became a cultural sensation and a source of inspiration for discussions on life style, etiquette and media ethics. Particularly young people use Chan’s meanwhile famous quotations and make parodies of these quotes [YouTube: Bus Uncle; Wikipedia:The Bus Uncle; Zittrain 2008:211].

Dog Poop Girl - South-Korea, 2002

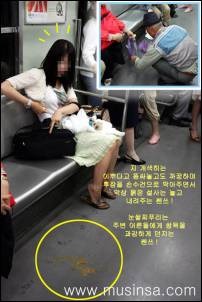

Dog Poop Girl

|

|---|

In 2002 a remarkable demonstration of the power of internet occurred in South-Korea. In the underground a woman’s dog shits on the floor. She refuses to clean it – even when she is offered a tissue – but she does clean her dog. Several fellow passengers get very upset, but the woman’s reactions become increasingly assertive. She gets off at the next stop. A picture was taken of this incident and published on internet with the title ‘gae-ttong-nyue’ (dog shit girl). The person who did this incited everyone to collect information on this dog possessor, her family and her work. She was identified by others who had seen her dog before. In no time her identity and her past were revealed; every single detail of her life could be watched by anyone on internet. The incident was national news in South-Korea and she was even topic of discussion in churches. The subsequent avalanche of criticism and public humiliation led to the loss of her job at the university. ‘Dog poop girl’ became the most wanted search term among South-Korean internet users.

In de Washington Post beschreef Jonathan Krim dit incident als een test van het schaamtevermogen van het internet [Krim 2005]. Het is niet nieuw dat het internet gebruikt wordt om rekeningen te vereffenen. Natuurlijk is het onfatsoenlijk als hondenbezitters de poep van hun hond in openbare ruimtes niet verwijderen. Maar was het fair om de ‘dog poop girl’ te transformeren in een schurk die over de hele wereld bekend is? Was de internetmeute hier niet te ver gegaan? Kan de digitale razernij niet meer worden afgeremd? Gaat deze vorm van publieke vernedering niet veel te ver? In the Washington Post Jonathan Krim described this incident as a test of the internet’s power to shame [Krim 2005]. Using the internet to settle scores is not new. Of course it is indecent when dog possessors do not remove their dog’s shit in public spaces. But was it fair to transform the ‘dog poop girl’ into a villain who is known all over the world? Didn’t the internet crowd go over the top in this case? Is it impossible to curb the digital rage? Doesn’t this form of public humiliation go way too far?

Several people from all over the world used this incident as an example for their own actions. They record their neighbours’ anti-social behaviour, who let their dogs empty their bowels on the pavement without cleaning it. They post pictures in the neighbourhood and put them on internet. They use the power of internet to push a norm: you are morally obliged to clean your dog’s shit in public spaces, you cannot dump rubbish on your neighbours’ pavement, you cannot pee in the street, you cannot jump the queue, and so on. By means of a cyber hunt in the blogosphere norm violators are traced and digitally branded [Solove 2007]. In this process their right of privacy is drastically violated — the bloggers believe they have lost this right because they have behaved indecently.

Star Wars Kid: Ghyslain Raza

|

|---|

On 4 November 2002 a Canadian teenager, Ghyslain Raza (1988), used the video camera of his grammar school to record himself on video while he is clumsily swinging a golf ball scoop as if it is a light sword from the Star Wars films. Raza only did this to amuse himself, but he forgot to erase the rather awkward mock fight. In the spring of the following year the recording was discovered by somebody else. He first distributed the recording among his friends and then published it on internet [YouTube: Star Wars kid].

We want privacy for ourselves, but are very curious about the foolishness of others. In 2006 the ‘StarWars Kid’ was the most popular viral video on internet. The film was downloaded 900 million times [BBC 27 November 2006]. Several parodies were made of it, of which some were shown on the American television at ‘prime time’. The ‘StarWars Kid’ himself was traumatised by it and did not make any attempt to cash in on his involuntary fame. Raza became a ‘welebrity’ against his will. He himself only wanted one thing: “I want my life back”.

In 2005 the boy’s family took legal proceedings against the families of his school friends and claimed a large compensation. Due to the unasked-for media attention the boy would suffer moral damage. “He had to endure, and still endures today, harassment and derision from his high-school mates and the public at large”. Besides, he had to undergo psychiatric treatment for an indefinite period of time. The case was settled. The StarWars Kid was not the first case of cyber bullying, but it was on of the best known one, because the video images were linked to the popular film series Star Wars [Wikipedia: Star_Wars_kid; idem_nl].

Blinded date: you’re on candid internet - U.S.A., 2006

Early September 2006 Jason Fortuny, a freelance graphic designer and network administrator from Seattle, published an advertisement in the section ‘Casual contacts’ of Craigslist.org. According to Alexia.com Craiglist was ranked no. 10 on the list of most popular sites in the USA in 2007 (ranked no. 11 at the end of 2008). The section ‘Casual contacts’ is a virtual market for people looking for once-only adventures and anonymous sex partners.

Jason received 178 reactions to his personal ad and published them on his own website: craigslist-perverts.org (now offline). As he had pretended to be a woman looking for a dominant sex partner the reactions were all men’s. Jason not only published the names of the men who had reacted to his advertisement, but also their nude pictures and the names of their wives (there were, by the way, also reactions from single males). This way he destroyed their reputations, careers and marriages at one go.

It was meant to be a ‘joke’. But in reality it was an unsavoury, reprehensible and harmful joke. Generally people with a little decency do not publish private e-mails, unless there are very good reasons to do so. But the men who had reacted to his advertisement had not done anything illegal – at the very most something ‘indecent’. Jason only demonstrated that someone is capable of ruining lives online. We have known for a while that this is also possible in local communities and networks. With the largest megaphone in the world fairly random individuals are publicly humiliated and digitally branded. The privacy of the victim is pushed aside by virtual popular tribunal (“such a person forfeits his right to privacy”) and the ritual sacrifice of the witch may begin.

In the debate ensuing from Jason’s initiative on internet he was celebrated as an agent provocateur by some, whereas others discarded him as a sociopath. As a result of his experiment two men lost their jobs. When he was indicted by John Doe in April 2008, Jason quickly eased off and removed all references to the lawsuit. On 18 April 2009 Jason Fortuny lost his court case and was ordered to pay $74,252.56 to the anonymous plaintiff [Wikipedia: Jason_Fortuny; Jesdanum 2006; Chonin 2006; Doe v. Fortuny 2008].

Julie’s verkrachter - U.S.A., 2005

In the summer of 2005 ‘Julie’ published a remarkable and repulsive story on dontdatehimgirl.com (DDHG). On this web forum abused women are encouraged to open up their hearts about the outrageous behaviour of their ex-boyfriends. Julie’s story was as plain as day: she indicted a man named Guido, who had plied her with liquor and then raped here (also anally). Besides, he had given her a sexually transmitted disease with this misdeed. “The whole time the greasy Italian piece of shit raped me, he kept on saying he had genital warts and that I deserved to have them, too, because I was a slut.” She felt humiliated, got depressed and tried to commit suicide. The story was accompanied by a photo of the perpetrator. The reactions are obvious: “That filthy bastard belongs in prison. We should put up his photo everywhere and show everyone what he has done.”

In the summer of 2005 ‘Julie’ published a remarkable and repulsive story on dontdatehimgirl.com (DDHG). On this web forum abused women are encouraged to open up their hearts about the outrageous behaviour of their ex-boyfriends. Julie’s story was as plain as day: she indicted a man named Guido, who had plied her with liquor and then raped here (also anally). Besides, he had given her a sexually transmitted disease with this misdeed. “The whole time the greasy Italian piece of shit raped me, he kept on saying he had genital warts and that I deserved to have them, too, because I was a slut.” She felt humiliated, got depressed and tried to commit suicide. The story was accompanied by a photo of the perpetrator. The reactions are obvious: “That filthy bastard belongs in prison. We should put up his photo everywhere and show everyone what he has done.”

But Julie’s story was a total pack of lies. In reality ‘Guido’ was Erik, a friend of ‘Julie’s’. Eventually she admitted that the horrible story was only a joke [Green 2006].

|

Vermijd de bedriegers

“To post a cheating man to our easy-to-use search engine, tell us about him by sending an e-mail to [email protected]! Give us his name, age, and tell us where he lives as well. If you have a photograph, we’ll post that, too! By e-mailing DontDateHimGirl.com a request to post a cheater, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.”

|

Which woman hasn’t ever warned another woman about one of her ex-boyfriends? This form of informal social control has always existed and has certainly been successful: people may be warned for men who abuse their beloved, in order to prevent recidivism. But with the site DDHG the classic informal mechanism is formalised and blown up out of all proportions worldwide. The men appearing on DDHG are branded as ‘rotten apples’ – regardless of whether the message that is published about them is true or not. Even if they have not committed a crime – apart from a few exceptions – and even if someone tries to better his life after a slip made in the past. Of course the indicted men have the opportunity to sue the woman who published this information. But in that case they first have to find out who this woman is. The postings on DDHG are usually published anonymously.

Another option is indicting the site itself. Can the DDHG be held liable for posting a fake message or a message that invades the privacy of the indicted men? The owner of DDHG, Tasha Joseph, believes she is not responsible for the comments written by others. She appeals to section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, offering specific protection to administrators of interactive internet services. Moreover, the Terms of Use of DDHG disclose that the user is “solely responsible” for what she sends to the site. But, as Julie Hilden [2006] remarked, it is still the law and not the site which determines who is responsible.

On internet there is nothing —apart from a personal moral— stopping someone from slandering another person without going unpunished. Nobody knows to what extent all those stories in dontdatehimgirl have been made up [Keen 2007:91]. None of the allegations on DDHG requires any proof. All charges are posted anonymously on the site: rape, paedophilia, manslaughter, addiction. From behind the wall of virtual anonymity harmful harangues are fired without any correction of the truth. Defamation and slander can be disseminated directly into the public space of the virtual world, without interference of selective mechanisms.

There is, by the way, also a counterpart of Don’tDateHimGirl. On the site GreatBoyfriends.comwomen can recommend their ex-boyfriends to other women. “Who doesn’t know a great guy (or girl) who is shockingly, still single? Maybe it’s your best friend, your not-for-me ex, your adorable brother — you get it.” Er bestaat overigens ook een tegenhanger van Don’tDateHimGirl. Op de site GreatBoyfriends.com kunnen vrouwen hun exen aanbevelen bij andere vrouwen. “Who doesn’t know a great guy (or girl) who is shockingly, still single? Maybe it’s your best friend, your not-for-me ex, your adorable brother — you get it.”

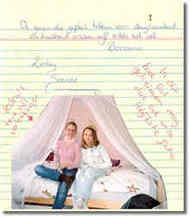

Sex diary of students - The Netherlands, 2002

In November 2002 there was commotion in the student world of Utrecht, because a ‘sex diary’ of two students circulated on the internet. The diary was stolen from the room of one of the students, scanned and posted on the exchange programme KaZaA. In the diary the two psychology students exchange their sexual experiences, describing the boys and rating them with stars and marks. The students describe their conquests with the most intimate details. They tell about torn condoms, how they wake up beside a young man and do not know who he is anymore, how he ended up there and what they have done.

In November 2002 there was commotion in the student world of Utrecht, because a ‘sex diary’ of two students circulated on the internet. The diary was stolen from the room of one of the students, scanned and posted on the exchange programme KaZaA. In the diary the two psychology students exchange their sexual experiences, describing the boys and rating them with stars and marks. The students describe their conquests with the most intimate details. They tell about torn condoms, how they wake up beside a young man and do not know who he is anymore, how he ended up there and what they have done.

The interest in the sites which published the sex diary was huge. The boys mentioned in the diary (by name, phone number and sexual achievements in bed) were swamped with torrents of abuse and badgering. A number of the twelve young men disconnected their phone numbers. According to student magazine Smoel printed copies of the sex diary circulated in Zwolle, in full colour and stapled. A website was put on air for the two students: the Sanne and Lesley Fanclub, selling T-shirts and other paraphernalia.

The students were shocked, but did not take it lying down. Their lawyer required all sites that published their diary or referred to it to stop this immediately. The police investigated the way in which the diary had become public. Hosting providers were frequently called with the request to remove the diary files from the internet. Website owners were called as well. Nearly all providers and website owners complied with the request. This is the reason why the diary is hard to find now. Publication of the diary falls within article 31 of the Dutch copyright act. This act states that publication of a copyright protected document is punishable. A diary is a copyright protected document, particularly because it is an exchange of letters.

The students were shocked, but did not take it lying down. Their lawyer required all sites that published their diary or referred to it to stop this immediately. The police investigated the way in which the diary had become public. Hosting providers were frequently called with the request to remove the diary files from the internet. Website owners were called as well. Nearly all providers and website owners complied with the request. This is the reason why the diary is hard to find now. Publication of the diary falls within article 31 of the Dutch copyright act. This act states that publication of a copyright protected document is punishable. A diary is a copyright protected document, particularly because it is an exchange of letters.

When reducing the case to theft of copyright protected documents it seems to be a simple one. Such a violation of privacy and copyright can be fought with the normal legal means. Yet, these and similar sex diary hypes remain remarkable phenomena. “Can you imagine anything more unusual? In an environment where sexual material is available on a scale mankind has never seen before, a hardly titillating story of two young girls experiencing rather innocent sex is the great sensation. Only because it was real” [Francisco van Jole, NRC 2.12.2002].

Diary of a coke officer - Nederland, 2006

On 11 May 2006 the populist web forum GeenStijl published intimate details from the diary of Ernst Wesselius, public prosecutor on Bonaire. Wesselius had accidentally made his diary accessible on internet, together with 448 confidential documents with information on bodypackers, money laundering practices and petty crime. For fear of legal prosecution these documents were not published, but the weblog does quote some intimate sexual scenes from his private life story. These are candid stories about his sexual fantasies, his experiences with prostitutes, his sneaky visits to porno cinemas and about masturbation. He also describes how, during a police investigation into a large-scale car theft, his business card suddenly showed up via a prostitute. “I will never forget my feeling of that moment, it was as if my whole world completely collapsed, I wished I could have disappeared through a large hole in the ground forever.”

The shock was even bigger when he noticed that GeenStijl and also the newspaper the Telegraaf started quoting from his ‘personal story’, which was only meant for his own eyes. “I wanted to sort my life out. The fact that this has reached other people is the worst thing that could have happened” [Telegraaf]. The confidential documents, together with his life story, had been put in a file on his computer, which was accessible to the outside world via LimeWare (a music exchange programme). At least, that was the statement given by GeenStijl and the Telegraaf. But investigation of Wesselius’ computer showed that this could not be the case, because no LimeWare software had been installed on it [Elsevier 17.5.2006]. Wesselius himself said to have ‘no idea’ how these documents could have gone public. “I only know how to switch the computer on and off. It is terrible. I have never exchanged music on that computer, I only write texts and send emails” [Telegraaf 13.5.2006]. Therefore, the confidential information that ended up in the street via the computer of the public prosecutor may have been stolen.

Together with the Telegraaf GeenStijl succeeded in badly damaging someone by quoting from personal documents which had been obtained in a dubious way. Exposing that criminal investigation documents are freely available via internet, due to incompetent acting of a public prosecutor, serves a social interest. But this does not apply to damaging the private person — this has no other purpose than offering sensation by trampling on someone else. This is not ‘funny’ and has nothing to do with ‘the exploration of frontiers’, and everything with passing elementary moral limits and defying forms of civilization. Wesselius reacted furiously: “It is awful that your private life is thrown away. Your feelings are torn in all directions. Fortunately I only received good reactions: one hundred percent of the people thinks it is an outrageous disgrace.”

Teacher loses patience - The Netherlands, 2008

It happened earlier before and elsewhere, but in November 2008 a video appears in which a teacher of the municipal grammar school in the city of Utrecht hard-handedly removes one of his pupils from the classroom. A pupil has to leave the classroom without his bag. Another pupil tries to make off with the bag. But he is roughly removed from the classroom, bag and all, by economics teacher Jongerius. Another person filmed the incident on his mobile, provided it with text and music at home, and dumped in on GeenStijl.

The principal of the school, Hanneke Taat, emphasised that the film only reveals part of the truth. “A teacher should not lose his patience, but sometimes they make it very hard for him. This film only shows one side of the case. We do not exactly know what preceded it. We are trying to find this out.” Three students of the comprehensive school in Utrecht were suspended. But the damage had already been done and the film can still be watched on internet. A small film on internet and the school reputation is busted. At some schools mobiles are forbidden in class and must be put away in lockers.

Prins on the journalistic pillory - The Netherlands, 2004

One of the first victims of the Dutch shocklogs was Trudy Prins, manager of Stivoro (information organisation in the field of smoking). It started on 2 January 2004 with an editorial published in GeenStijl, in which the number of people intending to stop smoking according to Stivoro was contested. The editorial staff of GeenStijl then asked its visitors to send e-cards to Prins or to call her. She was flooded with hate mails, publication of personal details and threats. There was even the suggestion of sending a paedophile to her house to rape her children anally. The editorial staff of GeenStijl initiated it, but declines any responsibility for what their visitors (Dutch: ‘reaguurders’, something like ‘reacreeps’) write down in the weblog.

Due to appropriate instigations of the editors of GeenStijl the rage became more and more threatening:

- “It is as if there is a kind of rage smouldering in society, aimed at random people. It all started with a message on a website, somebody reacted, and again somebody reacted. In no time they had put my mobile and home phone number on internet. And I received phone calls with the tenor: we know where your children go to school. People used to send you a postcard when they disagreed with you. But now it keeps going on. One person wrote something that was going nearly too far. The next one went even further. One moment ‘whore!’ was the kindest thing that was shouted through the phone” [Trudy Prins, in Trouw: 15.3.2004].

And each counter action has a reaction with even grosser use of words:

- “When I asked the provider if all this could be published, I was abused even more. An enormous dose of aggression was poured over me. All anonymous of course, although I could trace a phone number of those who sent me vicious text messages. When I called them back, they hung up” [idem].

Trudy Prins received nonstop phone calls for days. She was not sure anymore to what extent she should take the threats seriously.

- “I only thought: these people are too busy mailing to come here. But I was slandered so immensely that there only had to be one person who thought he would do the world a favour by getting rid of me.”

Prins considered reporting this hate campaign. But the digital police informed her that the chance of catching them was very small, that an investigation into the origin of these texts would probably generate new hate messages again and that the perpetrator would probably get no more than a light community service. She eventually refrained from legally defending herself. But the Stivoro foundation succeeded in putting so much pressure on the provider of GeenStijl, that the company ended its cooperation with the web log. As a result of Trudy Prins’ threats GeenStijl temporarily went off the air, but appeared online again a few months later. “GeenStijl was temporarily off the air, in order to cling fiercely growling to Stivoro’s trouser-leg again via another hosting provider” [WebWereld].

|

The law of mud wrestling

What can you do if you have the honour of being the target of the mob of a shocklog? In almost all cases it is unwise to react to the content. Who does so is immediately covered with mud. It only encourages the unseemly mob to go even further. Here a conventional wisdom applies: ‘Who is shorn has to sit still’. And also: ‘Never wrestle with a pig. You both get dirty, but the pig likes it’. Ignoring public attacks is often the best way to contain them.

|

The gutter journalism of GeenStijl operates according to a fixed pattern. With a first move of the editors the ‘reacreeps’ are invited to open up their hearts anonymously about a person they dislike for some reason or another. The ‘reacreeps’ outdo each other in malicious disqualifications, torrents of abuse and threats. After publication of phone number and address of the victim the latter is then privately harassed by the most agitated ‘reacreeps’. Defamation, slander and threats form the unseemly recipe of an editorial board that always cowardly hides behind its ‘reacreeps’ and tries to evade all responsibility for what happened. Who opposes this is sure to get an even more malicious treatment. Shameless to the bone, but with only one goal in mind: becoming more controversial and high-profile than other provoking or shocklogs.