Herbert Spencer

[1820-1903]

Herbert Spencer, a British philosopher and sociologist, played a significant role in the Victorian era's intellectual life. His fame at the time equaled Charles Darwin's as one of the leading proponents of evolutionary theory in the middle of the nineteenth century.

What made Herbert such a famous sociologist in his era ? Get to know more about Herbert Spencer’s life and career path in the article below.

I. Herbert Spencer biography

Herbert Spencer (1820 - 1903) was an English philosopher and sociologist. He was inspired by his father's anti-clerical and anti-establishment views since a young age. So, even as a small child, he displayed strong independence and defiance of authority. By proposing the notion of social Darwinism in his books, Herbert Spencer made a significant contribution to intellectual history and altered how people perceived society. One of the three sociologists who made a contribution to the structural-functional strategy intended to foster societal stability was Herbert. He thought that society is made up of different structures, each of which serves a specific purpose. The structures were interwoven, allowing the society to function efficiently and steadily when each structure did its duty correctly.

1. Who is Herbert Spencer?

In a little town called Derby, on April 27, 1820, the social Darwinist was born. William George Spencer, who founded the school and served as a teacher there, employed unique teaching techniques there. Spencer's father sent him to his uncle, the Reverend Thomas Spencer, to receive a formal education when he reached 13 years old.

In 1837, when Herbert Spencer was 17 years old, Queen Victoria began her 63-year rule of Britain. The Victorian era covered this time period. Instead of trying to dominate the country, the queen wanted to reign. The empire developed into the first global industrial power during this time, producing a significant portion of the world's textiles, iron, steel, and coal. Significant breakthrough advancements were also made in the arts and sciences during this time. Britain also entered the field of cutting-edge engineering.

2. Herbert Spencer early life

Herbert was drawn to learning from a young age and was exposed to several academic periodicals and books that belonged to his father because he was born into a family of teachers. Spencer's anti-authoritarian outlook was heavily inspired by his rebellious father, William George Spencer. Additionally, Herbert's father encouraged him to study science and later introduced him to the Derby Philosophical Society, where he gained additional knowledge of philosophical ideas. Spencer's schooling was also profoundly affected by his uncle, Reverend Thomas Spencer, who instructed him in Latin, math, physics, and radical political ideas. The extreme reformer viewpoints and ideas of Spencer's uncle influenced his economic and political views. Herbert Spencer turned down his uncle's suggestion to send him to Cambridge University in favor of concentrating on becoming a self-taught natural scientist.

Spencer, who had a variety of interests, finally studied to become a civil engineer for railroads but switched to journalism and political writing in his early 20s. He initially supported many of the causes of philosophical radicalism, and some of his theories (such as his adoption of a variation of the "highest happiness principle") had utilitarian resemblances. For example, he defined good and bad in terms of their pleasant or unpleasant consequences.

Herbert Spencer served as a writer and subeditor for The Economist financial weekly from 1848 to 1853. As a result, he met a number of political controversialists, including T.H. White, George Henry Lewes, Thomas Carlyle, Lewes' future fiancée George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans [1819-1880]), and T.H. Huxley (1825-1895). (1825-1895). Spencer's unwavering faith in his own views was accompanied by a stubbornness and a refusal to read authors with whom he disagreed, despite the wide range of viewpoints to which he was exposed.

II. Herbert Spencer Contribution & Impact

1. Herbert Spencer Contribution

Although he came to renounce the majority of these causes later in his life, Herbert Spencer advocated for a number of radical causes in his early writings, including land nationalization, the extent to which economics should reflect a laissez-faire philosophy, and the position and function of women in society.

Social Statics, or the Conditions Essential to Human Happiness, was Spencer's debut book, published in 1851. (The phrase "social statics," which was adapted from Auguste Comte, refers to the circumstances of social order and served as a prelude to a study of human development and evolution known as "social dynamics"). In this essay, Herbert Spencer offers a (Lamarckian-style) evolutionary theory-based account of how human freedom has evolved and a defense of individual liberty.

Herbert Spencer obtained a little bequest after his uncle Thomas passed away in 1853, enabling him to focus solely on writing without needing to work a normal job. The Principles of Psychology, Spencer's second book, was released in 1855. Herbert Spencer continued to hold Bentham and Mill in high regard, albeit in this work he concentrated on his objections of Mill's associationism. The Principles of Psychology was much less successful than Social Statics, but around this time Spencer started to experience serious (mostly mental) health problems that would affect him for the rest of his life. (Spencer later revised this work, and Mill came to respect some of Spencer's arguments.) He began to seek solitude as a result, and he grew more reluctant to be seen in public.

A System of Synthetic Philosophy (1862–1893), a nine-volume work that presented a systematic description of his beliefs in biology, sociology, ethics, and politics, was a protracted effort that he undertook despite discovering that his poor health limited the amount of time he could spend writing each day. This "synthetic philosophy" gathered a vast array of data from the many natural and social sciences in accordance with the fundamental ideas of his evolutionary theory.

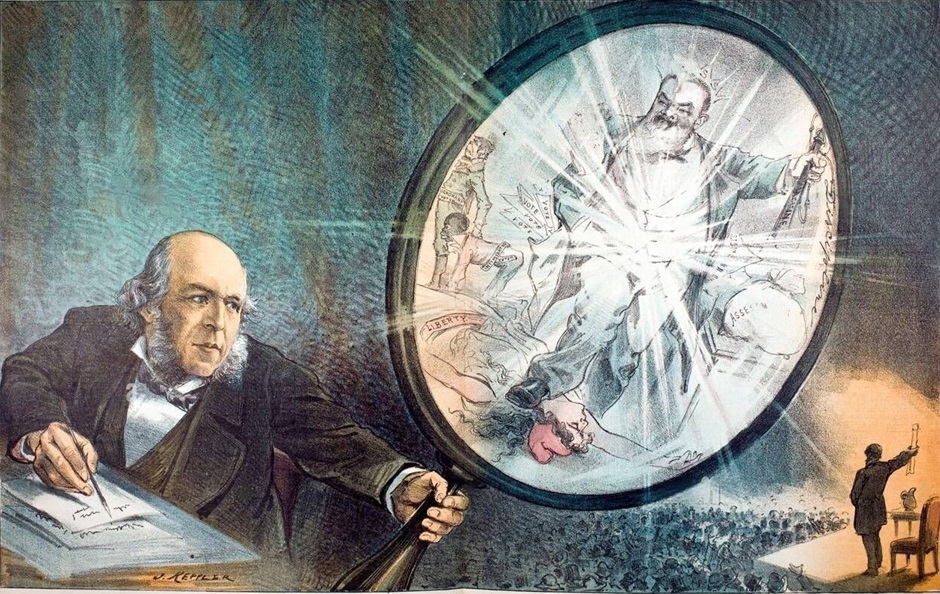

Although Spencer's Synthetic Philosophy was first exclusively accessible through private subscription, he also contributed to some of the top newspapers and publications of his time. His notoriety increased along with his works, and he had both radical intellectuals and well-known scientists as admirers, such as physicist John Tyndall and John Stuart Mill. For instance, Spencer's evolutionary theory had a similar impact as Charles Darwin's during the 1860s and 1870s.

2. Herbert Spencer impact

Herbert Spencer’s reputation was at its height in the 1870s and early 1880s, and he was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1902. Spencer's influence extended into the upper echelons of American society, and it has been claimed that, in 1896, "three justices of the Supreme Court were avowed "Spencerians"." But Herbert Spencer turned down the majority of the accolades bestowed upon him.

He is considered the most significant proponent of social development. He is also regarded as the founding figure of traditional evolutionists. He was named editor of "The Economist" in 1848. He had finished "Social Statics," his first significant book, by 1850. In the field of sociology, he is renowned for his theories on "Social Evolution" and "Organic Analogy."

Because the intellectual specialization he welcomed and projected expanded even beyond his expectations, Spencer's endeavor to combine the sciences displayed a sublime daring that has not been replicated. Although it provided the study of society a boost, his sociology was replaced by the development of social (or cultural) anthropology and was much more concerned with defending his social goals than he himself realized. Native Americans, for instance, are not the emotionally immature beings he had imagined them to be, and religion cannot be fully understood in terms of the souls of their ancestors.

III. Herbert Spencer contribution to Sociology

1. First Principles

It is challenging to understand Spencer's philosophizing in isolation from his non-philosophical work due to the breadth of his production, which extended beyond philosophy and into a number of other disciplines. Additionally, there are thousands of printed pages in Spencer that are difficult to understand. Herbert Spencer published extensively on a variety of topics, including sociology, psychology, and biology in addition to ethics and political philosophy. Unsurprisingly, a lot of this content has a similar theme running through it. No one now possesses the expertise necessary to come to terms with Herbert Spencer and assess his legacy.

Despite this warning, it seems reasonable to conclude that sociology has seen Spencer's influence most strongly, second only to ethics and political philosophy. The latter grounds and orients the former in many telling ways. Consequently, it would seem better to talk about his sociology before moving on to his moral and political theory. But in order to take up his sociological theory, it is necessary to briefly discuss the fundamental tenets that form the basis of his entire "Synthetic Philosophy."

As an axiomatic prolegomena to the synthetic philosophy, First Principles was published in 1862. The synthesis philosophy came to an end with the publication of The Principles of Sociology's final book in 1896. First Principles is primarily metaphysics, embracing all inorganic change and biological evolution, even if it is dressed up as speculative physics from the middle of the 19th century. The synthetic philosophy claims to demonstrate what follows from First Principles in excruciatingly precise detail.

In conclusion, civilizations were not just growing more cohesive, heterogeneous, and complicated. Their components, including their human members, were becoming more and more specialized and individuated, and they were becoming even more interconnected.

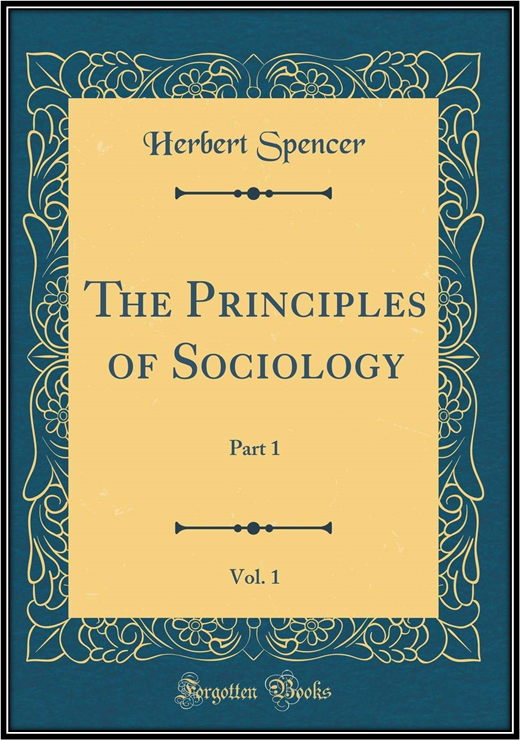

2. The Principles of Sociology

The Method and Much of the Content of The Principles of Sociology Have Been Considered Seminal in the Development of Modern Sociology. It speculatively describes and explains the entire arch of human social evolution using countless examples from the distant past, recent past, and today. Understanding Spencer's ethics will be especially helpful if you read Part V, "Political Institutions." "Political Institutions" caps his Principles of Ethics and the Synthetic Philosophy. They are its entire purpose.

According to Herbert Spencer, social evolution happens in four universal stages. These include 1) "primitive" societies with haphazard political cooperation, 2) "militant" societies with strict, hierarchical political control, 3) "industrial" societies with the collapse of centralized political hegemony and the rise of minimally regulated markets, and 4) spontaneously self-regulating market utopias where the role of government withers away. This cycle of consolidation and reversal, to which no society is immune, is fueled by overpopulation, which leads to violent conflicts between social groups.

Spencer's sociological thinking is clearly influenced by normative theorizing, notwithstanding his growing pessimism towards liberal advancement and world peace. Ethics and sociology are intertwined. We'll soon see how individualistic and utilitarian both of them were.

Spencer's standing in sociology has gotten worse. Although they presumably don't remember much about him, social theorists still recall him. However, this may be changing. While he was extensively discussed in the 19th century by new liberals like D. G. Ritchie, idealists like T. H. Green and J. S. Mackenzie, and utilitarians like Henry Sidgwick and Mill, moral philosophers have mostly forgotten about him. Additionally, 20th-century Oxford intuitionists like W. D. Ross and Moore, as well as ideal utilitarians like Hastings Rashdall, felt impelled to debate him. Herbert Spencer played a significant role in their intellectual environment. His influence on how they thought was not negligible. We must take Spencer more seriously than we do in order to comprehend them correctly.

3. Spencer’s “Liberal” Utilitarianism

In part, Herbert Spencer was a sociologist. But his moral philosophy was considerably more profound. In order to explain how our liberal utilitarian sense of justice originates, he primarily drew on evolutionary theory. He was what we now refer to as a liberal utilitarian in the first place.

Herbert Spencer, a utilitarian, treated distributive justice with the same seriousness as Mill did. Justice and liberty had the same meaning for him as they did for Mill. Spencer held that the "liberty of one, limited by the similar liberty of all, is the rule in conformity with which society must be formed," in contrast to Mill who connected basic justice with his liberty concept. Spencer's utilitarianism was also a genuine type of liberalism because, like Mill, he believed that liberty was inviolable. Respect for liberty also just so happens to be the optimal option from a utilitarian standpoint for both. As a result, utility and indefensible liberty were both entirely composable.

Equal freedom benefits cultures that absorb it and, ultimately, self-consciously invoke it, just like any moral intuition. And in cultures that uphold equal freedom as the cornerstone of justice, prosperity abounds and utilitarian liberalism spreads.

Insofar as properly enjoying equal freedom required recognizing and celebrating fundamental moral rights as its "corollaries," Herbert Spencer also took moral rights seriously. Equal freedom is specified by moral rights, which substantially clarifies its normative criteria. They outline the two things that are most crucial to human happiness: life and liberty. The moral demands of life and liberty are prerequisites for everyone's happiness. They ensure that each person has the freedom to use their faculties in accordance with their own values, which is the root of true happiness. Moral rights only provide us the opportunity to make ourselves as happy as we can; they cannot make us happy. As a result, they indirectly foster overall contentment.They are just as impregnable as the idea of equal freedom itself since they are "corollaries" of it.

Thus, basic moral rights also become intuitively apparent, but they are more particular than our more general intuitive understanding of the merits of equal freedom. Our nascent normative intuitions regarding the sanctity of life and liberty are afterwards transformed into strict legal rules by self-consciously internalizing and improving our intuitive sense of equal freedom, turning it into a principle of practical reasoning. Additionally, this is only a different way of saying that general usefulness thrives most when liberal values are seriously upheld. Moral societies are more content, energetic, and prosperous as well.

4. Rational Versus Empirical Utilitarianism

Be opposed to Bentham's inferior "empirical" utilitarianism, Spencer's version of utilitarianism was known to as "rational" utilitarianism. And although while he never referred to Mill as a "logical" utilitarian, it is likely that he did.

Don't undervalue what Spencer's "rational" utilitarianism meant from a metaethical standpoint. Herbert Spencer distinguished himself clearly from social Darwinism by describing himself as a "rational" utilitarian, demonstrating why Moore's controversial conclusion was incorrect. In response to T. H. Huxley's criticism that Spencer equated "survival of the fittest" and "good," Herbert Spencer contended that the two terms were not interchangeable.

He concurred with Huxley that, despite the fact that ethics may be described in terms of evolution, the appearance of humans preempted the natural battle for existence. Humans give evolution a "ethical check," which sets it apart from non-human evolution in important ways. Insofar as it outlines the "equitable bounds to his [the individual's] activities, and of the limitations which must be imposed upon him" in his relationships with others, "rational" utilitarianism constitutes the most sophisticated kind of "ethical check[ing]".

In sum, we start "check[ing]" the evolutionary battle for survival with an unparalleled level of skill and nuance once we start systematizing our nascent utilitarian intuitions with the concept of equal freedom and its derived moral rights. To enhance our well-being more than ever, we actively infuse our utilitarianism with strict liberal values.

IV. Herbert Spencer on Philosophy and Politic

1. Herbert Spencer Method

Generally speaking, Spencer's approach is scientific and empirical, and it was greatly influenced by Auguste Comte's positivism. Herbert Spencer believed that scientific knowledge is liable to change due to the empirical nature of science and his opinion that what is known—biological life—is going through an evolutionary process. The main thing about science, according to Spencer, is to adjust and change one's ideas as science progresses. But because scientific knowledge was fundamentally empirical, it was impossible to know anything that was not "perceivable" and could not be empirically tested. (Spencer has been criticized for failing to distinguish between perceiving and conceiving because of his emphasis on the knowable as perceivable.) Herbert Spencer wasn't a skeptic, though.

Spencer also used a synthetic approach. Each science's or field's goal was to gather evidence in order to identify the fundamental principles, rules, or "forces" that gave origin to these events. One could have explanations that were highly certain to the extent that such principles agreed with the findings of investigations or experiments in the other disciplines. Herbert Spencer took great care to demonstrate how each science's data and conclusions are important to and significantly influence the others.

2. "Human Nature"

Herbert Spencer maintained that all phenomena might be described in terms of a protracted process of evolution in things in the first volume of A System of Synthetic Philosophy, First Principles. According to this "principle of continuity," homogeneous creatures are unstable, evolving from simple to more complex and heterogeneous forms, and that this evolution represents a standard of progress. This theory of evolution gave the kind of variation seen by Darwin a comprehensive and "predetermined" structure, and Darwin's regard for Spencer was important.

Herbert Spencer believed that progress was necessary, but only in the grand scheme of things; his explanation of this process lacks any teleological elements. The phrase "survival of the fittest" was really first used by Spencer, not Darwin, but Darwin did use it in later editions of The Origin of Species. (However, neither figure addressed the fact that this attitude was far from general and was ambiguous—for it was unclear if one had in mind the "fittest" individual or species.)

Spencer's conception of evolution emphasized the direct impact of outside forces on the organism's development and incorporated the Lamarckian hypothesis of the inheritance of acquired traits. He rejected the idea that evolution was driven by the traits and growth of the organism itself and by the straightforward idea of natural selection.

3. Herbert Spencer Religion

Because Herbert Spencer believed that knowledge of phenomena required empirical demonstration, he argued that there was something that was basically "unknowable" because we cannot know the nature of reality in and of itself. (This entailed having complete knowledge of the nature of force, motion, matter, and space, time, and force.)

We cannot know whether there is a God or what his or her characteristics might be, according to Herbert Spencer, because we cannot know anything that is not empirical. Spencer's general attitude toward religion was agnostic, despite the fact that he had harsh criticisms of religion, religious theory, and religious practice—these being the proper subjects of empirical research and evaluation. He claimed that theism cannot be accepted because there is no method to learn about the divine and no way to test it. While we cannot know whether a religious belief is true, we also cannot know whether a religious belief is untrue (at least not in its core).

4. Herbert Spencer Philosophy

a. Moral Philosophy

Herbert Spencer believed that human civilization follows the same evolutionary principles that biological creatures do in their growth. Spencer considered human life as existing on a continuum with, as well as the completion of, a protracted process of evolution. As with the digestive system or a lower organism, Spencer believed that society—and social institutions like the economy—can operate without outside intervention. However, in making this claim, Spencer failed to recognize the crucial distinctions between "higher" and "lower" levels of social organization. Herbert Spencer believed that every aspect of the natural and social world mirrored "the universality of law." Moral science can determine what kind of laws encourage life and lead to happiness by starting with the "laws of life," the circumstances of social existence, and the realization that life is a fundamental value.

Because Spencer's ethics and political philosophy is based on a theory of "natural law," he argued that evolutionary theory might serve as the foundation for a thorough political and even philosophical theory. Herbert Spencer realized that there are disparities in what exactly constitutes happiness given the distinctions in temperament and character among persons (Social Statics [1851], p. 5). However, in general, "happiness" is defined as the excess of pleasure over pain, and "the good" is whatever supports the survival and growth of the organism or, to put it another way, whatever creates this surplus of pleasure over pain. Happiness, then, is that which a particular human being naturally desires and represents the total adaptation of an individual organism to its surroundings.

Although Spencer's opinions are obviously fundamentally "egoist," he believed that sensible egoists would not compete with one another in the pursuit of their own self-interest. To support those who are not directly related to oneself, such as the unemployed and underemployed, is therefore not only against one's best interests, but also promotes indolence and stunts evolution. In this sense at least, Darwinian concepts helped to justify, if not explain, social injustice.

b. Political Philosophy

Spencer, despite his egoism and individuality, believed that group life was significant. Society could not do or be anything other than the sum of its parts since the relationships between the components were based on mutual dependence and the importance of the individual "part" to the collective. This point of view is clear in his later works, some of which are included in successive versions of The Man versus the State, as well as in his first significant substantial contribution to political philosophy, Social Statics.

As was previously said, Herbert Spencer maintained a "organic" view of society. However, as was also mentioned above, he claimed that "liberty" was necessary for an organism to flourish naturally, which allowed him to (philosophically) advocate individualism and the existence of human rights. He insisted on an extended laissez faire policy because he was committed to the "law of equal freedom" and believed that legislation and the state would inevitably interfere with it.

According to Spencer (The Man versus the State [1940], p. 19), "liberty is to be measured, not by the nature of the government machinery he lives under [...] but by the relative paucity of the restraints it imposes on him"; the true liberal seeks to repeal those laws that coerce and restrict people from acting as they see fit. Herbert Spencer therefore followed earlier liberalism in holding that a law is a restriction of freedom and that a restriction of freedom is bad in and of itself and only justifiable when it is essential to the preservation of freedom. The only duty of the government was to uphold and defend individual rights. Spencer argued that the state should not be involved in matters of education, religion, the economy, or health care for the poor or sick.

So it should come as no surprise that Herbert Spencer insisted the early utilitarians' justifications for law and authority as well as the foundation of rights were false. Additionally, he disagreed with utilitarianism's model of distributive justice since, in his view, it was based on an equality that neglected biological efficiency and, more importantly, desert. Spencer argued further that the utilitarian view of the law and the state was incoherent because it implicitly presupposed the existence of claims or rights that are independent of positive law and had both moral and legal weight.

Finally, Herbert Spencer makes an argument against representative, parliamentary governance by stating that it displays a kind of "divine right" and that "the majority in an assembly has power that has no limitations." In Spencer's view, political organization should be modeled like a "joint stock corporation," where the "directors" can never act for a given good except on the express intentions of its "shareholders," and government action requires not merely individual permission. Herbert Spencer argued that parliaments are no different from tyrannies when they try to do more than just uphold the rights of their citizens, such as "imposing" an idea of the good—even if it is just on a minority.

V. Herbert Spencer Death & Legacy

1. Where was Herbert Spencer buried?

Herbert Spencer was recognized as the finest living philosopher at the time in the final years of his life. His writings were translated into other languages and were read all over the world, allowing him to support himself off the proceeds from the sale of his books and other works. His life, however, took a gloomy turn when he abandoned many of his well-known libertarian political beliefs in the 1880s. As more of his contemporaries passed away, readers lost interest in Spencer's new work, and he experienced reader disinterest.

Herbert Spencer was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature in 1902 but did not receive it. Spencer's final years were marked by the collapse of his early optimism and the replacement of that attitude with pessimism about the state of humanity. Nevertheless, he spent a lot of time bolstering his points and guarding against incorrect interpretations of his ground-breaking non-interference theory. Many intellectuals, like American philosopher William James, idolized him, but he was also regularly criticized for being petty, hypochondriac, and sentimental. He passed away in 1903 and is interred between George Eliot and Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery.

2. Herbert Spencer's Legacy

Even while Spencer's viewpoint is now mostly despised, it once appealed to powerful conservatives and laissez-faire businessmen, such industrialist Andrew Carnegie, and infuriated socialists of the day. According to Lightman, "Spencer detested socialism because he believed socialism was all about protecting the weak." He perceived that as interfering with the evolution's natural course.

According to David Weinstein, a political scientist at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, Herbert Spencer envisioned a society that was more moral and just, and he thought that "letting the market go" was the best way to accomplish that. Spencer, according to Weinstein, promoted the viewpoint that "those who survive the fight are by definition not only the fittest but also the best morally." Therefore, it defines "good" as "survival." Anything that endures is by definition good.

Later philosophers attacked Spencer's reasoning, particularly in the first half of the 20th century. His detractors charged him with engaging in what is today referred to as the "naturalistic fallacy"—roughly speaking, the error of attempting to infer morals and ethics from nature. In his 1903 book Principia Ethica, British philosopher G. E. Moore—who was extremely critical of Herbert Spencer—introduced the phrase. According to Weinstein, Spencer's reputation among serious philosophers was seriously damaged by Moore's criticism (though Moore, too, has largely disappeared from history).

More significantly, much of Spencer's legacy has yet to be fully mined by modern scholars who continue to labor over the works of other classical figures with little to show for their efforts. On the other hand, if they turned their attention to Spencer, they would find what can only be described as a hidden legacy of useful ideas. In contrast to early European sociologists, early American sociologists adopted Herbert Spencer's view of evolution, and the central theoretical contention is still present in a wide range of literature today, including the study of organizations as they expand and change, of communities as they divide into sectors and neighborhoods, and of macro-level theories of societal evolution. Whatever the case, Spencer's general principles regarding the growth, differentiation, and integration of the matter constituting superorganisms or systems organizing organic bodies manifest themselves in the dynamics of differentiation that take place in societies and their subunits, such as organizations and communities.

VI. Facts about Herbert Spencer

1. He had a brief liaison with author George Eliot

George Eliot was a multi-talented writer, translator, and thinker who included many modern scientific and philosophical ideas into her work, and Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) was a major proponent of evolutionary biology. Their friendship reflects a true coming together of the minds. It appeared as though romance might be in the air at one point, but Spencer was turned off by Eliot's unusual appearance. Later, Eliot connected with George Henry Lewes and became his common-law spouse. When he was in a particularly irritable mood, Herbert Spencer would put on his "mad outfit," which he possessed and which he often wore.

2. He introduced the idea of the fittest surviving

As we've shown in our selection of the top Charles Darwin facts, Darwin wasn't the first to put up an evolutionary theory, nor was he the first to use the term "natural selection." Although Darwin would popularize the expression "survival of the fittest," Herbert Spencer was the first to use it to describe how natural selection operates, i.e., that which is best adapted to its environment will survive and reproduce. Herbert Spencer first used the phrase in his 1864 book Principles of Biology.

3. Seven years before Darwin published his theory of evolution, Spencer actually put out one

Herbert Spencer wrote an article titled "The Development Hypothesis" that was published in The Leader in 1852. Spencer's idea lacked a strong theoretical framework, hence it was not particularly taken seriously. Nevertheless, one year before Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published, Spencer, not Darwin, is credited for coining the phrase "theory of evolution" in an essay.

4. Although Herbert Spencer didn't actually create the paperclip, as has been claimed, he did create something very similar

Spencer asserted that he created a "binding-pin" in 1846 and that Ackermann & Co. sold it in his 1904 autobiography. Although it resembled the "cotter pin" or split pin more than the current paperclip, this was in fact employed to secure sheets of paper or "unstitched publications" together.

5. Throughout the nineteenth century, Herbert Spencer had enormous influence, but his standing significantly deteriorated in the twentieth

In his book First Principles, Spencer developed a philosophical framework for evolution that combined Darwinian and Lamarckian models (Lamarck was the one who first put forth the concept of "acquired characteristics," whereby improvements or adaptations cultivated over the parents' lifetime would be passed on to their progeny). He kept adding to this, compiling his philosophical ideas into the System of Synthetic Philosophy in 1893. He was revered as a titan in both Britain and America. After his passing, though, his standing declined.

Spencer's attempt at an evolutionary philosophy was favored by the American philosopher and pragmatist William James (1842–1910), at least when he was a young man. Spencer's "whole system [was] wooden, as though banged together out of cracked hemlock boards," the author later remarked. Who reads Spencer anymore, a sociologist in America questioned in 1937? Who exactly? But it's important to know about him because of the impact he had on Victorian culture.

WHAT IS YOUR IQ?

This IQ Test will help you test your IQ accurately

Maybe you are interested